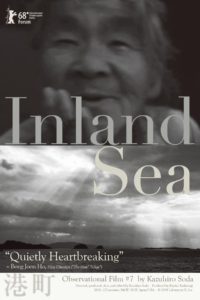

The seaside town of Ushimado is a bit of a microcosm of Japanese rural society. The trend of ageing rural populations and the absence of technological-driven development threatens to create a ghost town within a decade. It’s a perfect playground for Kazuhiro Soda’s INLAND SEA (港町), or Observational Film #7 if you prefer.

Following Soda’s Oyster Factory, the distinctive filmmaker turns his eye back to this small town. Much of the early part of the film focuses on Mr Murata, an elderly fisherman, who wonders if it is time to stop delivering fish to the town at the tender age of 86. Soda and his wife/producer Kiyoko Kashiwagi wander around the town gathering footage and stories from the residents.

The whole traditional process is followed, from Murata repeatedly stating that now “tools cost more, [but] fish are cheaper to sell.” We see their value as we watch a kind of reverse auction for the catches of the day, and then follow shop-owner Mrs. Kosa around down delivering fish on a planned route she’s traversed since she got married, 55 years ago.

Soda and his wife don’t quite adhere to a strictly “observational” approach, as they can frequently be heard off camera asking questions and making commentary. Shot in stark black and white, most of these questions simply prompt stories that were already there waiting to be discovered.

This tactic pays off in numerous moments that you couldn’t script, some hilarious and some heartbreaking. At one point, they are chatting to a couple who tend to an alley full of cats, because Soda loves observing cats, especially the white (Shiro) kind. They almost serve as a logo for his films. By happenstance, a woman walks past with a “Dog Catcher” jacket on. They follow her to discover she is tending a grave for an ancestor she can’t remember the name of, an apt analogy for the entire rural fishing community.

In other instances, this techniques leads to some unexpectedly touching moments. An elderly woman, who has been portrayed as a bit of a town crank up until this point, invites them up to view a hospital that used to be a school. Unprompted, she reveals her tortured past: a step-parent who wouldn’t allow her to go to school, a son that was taken away years before, and an incredible feeling of loneliness. “That’s why I’m ready to die,” she pragmatically explains.

Nevertheless, Soda and his wife find a rare kind of optimism and endurance in the people of this town. It’s the kind of storytelling that isn’t as sensational as podcast and Netflix true crime series, but it gets deep into the heart of humans. Ending the film on a single colour shot of the harbour, it’s a visual restoration and a sincere hope that Japan will rediscover the importance of these communities.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | Japan | DIR: Kazuhiro Soda | DISTRIBUTOR: TriCoast Worldwide Entertainment, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 122 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 11 June 2018 (SFF) [/stextbox]

2018 | Japan | DIR: Kazuhiro Soda | DISTRIBUTOR: TriCoast Worldwide Entertainment, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 122 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 11 June 2018 (SFF) [/stextbox]