Spike Lee’s BLACKKKLANSMAN opens with an extended scene from Gone with the Wind, often held up as an essential film in the American canon. Immediately juxtaposed with a blooper real of an actor (played by Alec Baldwin) spouting bigoted rhetoric, here it begins Lee’s conversation about cinema’s complicity in the institutionalised racism in the United States.

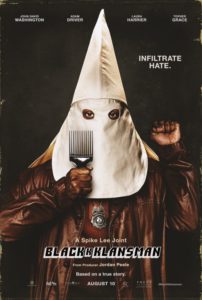

“Dis joint is based on some fo’ real, fo’ real shit,” an opening title reminds us, based as it is on the memoirs of Ron Stalworth (portrayed in the film by John David Washington). After joining the police in Colorado Springs as the first black cop in town, he soon gets undercover work investigating the local Civil Rights movement, and the student president Patrice (Laura Harrier). His career escalates when he infiltrates the local Ku Klux Klan chapter, using fellow cop Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) as his public face. His work soon connects him all the way to the top of the KKK and David Duke (Topher Grace).

BLACKKKLANSMAN can be viewed on a number of levels. To start with, it’s incredibly funny. Lee and his writing team instinctively recognise that the power of so-called ‘white power’ movements lies in their ceremony and artifice, not to mention the backing of hundreds of years of cultural racism. He immediately sets about tearing those sacred cows down. Some of it is cheap shots at ‘rednecks,’ but more wryly through the portrayal of David Duke as an out of touch politico.

Contrasting this is the strong message of black unity. Civil Rights leader Kwame Ture (played here by Corey Hawkins) warns of the ‘coming war’, but also of the importance of recognising beauty in the African American duality. A powerful moment comes with Lee rapidly cutting back and forth between a Klan initiation ceremony, and an Civil Rights elder recounting the brutal mutilation and death of a falsely accused rapist within his living memory. The point is clear enough: these institutions are our institutions, and we are all responsible for the history that comes with it.

Washington is a charismatic lead. Known mostly for his work as a pro footballer, he actually started his acting career at the age of 9 as a student in Lee’s Malcolm X. Harrier’s strength as a performer opens up a dialogue opens about the “war going on inside ourselves,” as posters of Blaxploitation films Shaft, Cleopatra Jones, and Superfly fill the screen. Through Driver, there’s an unexpected conversation about the dual identity of being Jewish and American as well.

As with most of Lee’s work, BLACKKKLANSMAN is fiercely political. What’s perhaps surprising, for a film set in the 1970s, is how sharply topical it is as well. There are frequent winking nods to “someone in the White House who embodies [hate]” and “America First” as a justification for that hatred. From Birth of a Nation, scenes of which are screened in the film, cinema has perpetuated those power structures, even allowing a reality TV star to rise to power on a platform based on division.

Lee uses the trappings of the Blaxploitation classics he name-checks, right down to the explosive finale. Yet the closing moments of the film segue into footage of the Nazis of Charlottesville in 2017, and the tragic death of Heather Heyer, Lee wants to remind us that life is not like the movies. A hero cop is one thing, but it’s our collective responsibility to hold leaders such as Donald Trump, who refused to call out the Nazis initially, to task at every turn.

The final shot of the film is a chilling vision of the American flag place upside-down, morphing into a black and white version before the credits roll. For some this might be interpreted as a display of disrespect, but most will tell you it is a universal symbol of distress. BLACKKKLANSMAN is a response to a country in crisis, and may be Lee’s most powerful commentary in years.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | US | DIR: Spike Lee | WRITER: Spike Lee, David Rabinowitz, Charlie Wachtel, Kevin Willmott | CAST: John David Washington, Adam Driver, Laura Harrier, Topher Grace | DISTRIBUTOR: Universal Pictures, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 148 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 16 June 2018 (SFF), 9 August 2018 [/stextbox]

2018 | US | DIR: Spike Lee | WRITER: Spike Lee, David Rabinowitz, Charlie Wachtel, Kevin Willmott | CAST: John David Washington, Adam Driver, Laura Harrier, Topher Grace | DISTRIBUTOR: Universal Pictures, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 148 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 16 June 2018 (SFF), 9 August 2018 [/stextbox]