When you visit modern day Tokyo, you can step inside a seven-floor sex shop right next to the Akihabara Station, running the gamut from ball gags to Blu-rays. Yet the pornography industry in Japan during the 1980s could rightfully be known as Photo Age, thanks to the magazine of the same name selling over 350,000 copies a month. A mixture of explicit photos and literature, the man behind it was Akira Suei. He was kind of the Larry Flynt of his day.

Based on his autobiographical essays, we meet Suei (Tasuku Emoto) in 1984 as he’s flicking through the pages of the latest issue of his periodical with a police official (dryly played by the recognisable Yutaka Matsushige). “Japan is a modern nation,” the cop chastises. “What if foreigners see this?” It’s a winking nod to a censorship system that continues to this day, and a great setup for a character who is posited as gently rocking the system throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

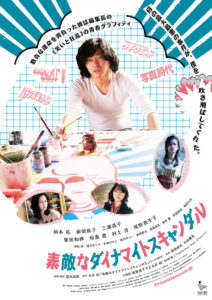

DYNAMITE GRAFFITI (素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル) is a title that references a childhood tragedy, one in which his mother blew herself and a lover up with dynamite. The incident is initially played partly for laughs, as authorities pick their way through the splattered red ‘graffiti’ of their remains. Yet it remains a focal point for writer/director Masanori Tominaga’s (Pumpkin and Mayonnaise) narrative, one that leaps through the years as though they were pages in one of Suei’s publications.

Tominaga has directed a number of intimate portraits over the years. The most esoteric (until now) was The Echo of Astro Boy’s Footsteps on the very particular subject of Matsuo Ohno, the sound designer for Astro Boy. So with Suei he has fertile ground for the exploration of a fascinating character. While we get flashes of the painstaking manual process of putting a magazine together back in the day, Tominaga is mostly interested in Suei’s odd jobs and love interests.

Much of the early part of the film, which chronologically begins in the late 1960s, is concerned with the frustrated artist finding his way in the world. From factory work to signboards, comics, and photography, a fair bit of time is spent before we get to his editorship of New Self, which like Playboy was a pioneering porn magazine that attracted contributions from renowned writers. It’s here he also begins his relationship with co-worker Fueko (Toko Miura), in a meandering subplot that sees her driven to be institutionalised. In this sense, Suei is portrayed like a romantic tragic character in one of Osamu Dazai’s novels (of which Tominaga adapted Pandora’s Box back in 2009).

At times DYNAMITE GRAFFITI is engagingly shot, with Yuta Tsukinaga’s blue and pink neon-lit photography filling frames with implied sex in the absence of outright nudity (of which there is a fair amount). A dissonant score occasionally gives way to some diagetic saxophone, which turns out to be a fleeting reference to the real Suei’s interest in the instrument. The Mamas & the Papas’ “California Dreaming” serves as a repeated meme to signify the changing of seasons.

A coda tells us that “Mr. Suei is now known as an essayist, editor, and sax player,” although you’d get no sense of how he got there from the semi-sleazy tail end involving the production of sex dolls. A mostly surface-level biopic leaves us with more questions than answers, so if your browser history is now filled with searches for retro Japanese erotic, you can thank director Tominaga.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Masanori Tominaga | WRITERS: Masanori Tominaga | CAST: Tasuku Emoto, Atsuko Maeda, Toko Miura | DISTRIBUTOR: Tokyo Theatres, New York Asian Film Festival (US) | RUNNING TIME: 138 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 29 June 2018 (NYAFF)[/stextbox]

2018 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Masanori Tominaga | WRITERS: Masanori Tominaga | CAST: Tasuku Emoto, Atsuko Maeda, Toko Miura | DISTRIBUTOR: Tokyo Theatres, New York Asian Film Festival (US) | RUNNING TIME: 138 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 29 June 2018 (NYAFF)[/stextbox]