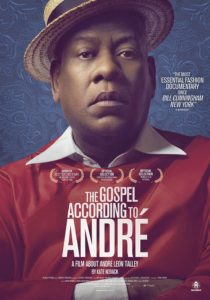

If you have watched anything documenting the fashion world in the last few decades, and there have been quite a few of them, you will undoubtedly have noticed at least one ubiquitous figure. Physically towering above his contemporaries, and unmistakable in his colourful caftans, André Leon Tally has been such an identifiable part of the industry that the contemporary fashion landscape would contain a swirling void without him.

Yet Kate Novack’s portrait of Tally is about so much more than fashion. Beginning with his origin story in the Jim Crow South of in Durham, North Carolina of the 1950s/1960s, Novack doesn’t simply represent Tally as a fashion doyen but as an avatar for the evolution of a nation. Describing his upbringing as Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory, Novack uses Tally’s career to paint a portrait of a man who transgresses what is traditionally “acceptable” for black masculinity.

It’s an impressive career too. Tally came up in the New York fashion scene of the 1970s, working with Diana Vreeland, and then at Andy Warhol’s Interview. He became the Paris bureau chief for Vogue, and ultimately editor-at-large for the fashion bible. What Novack captures in the amazing archive footage, and numerous interviews with Tally and his colleagues, is how influential the presence of a non-white person in that closed world was on other people of colour in the profession. In the press materials, Novack cites painter Kehinde Wiley’s notion of where “just being present represents a form of radicalism.”

Structurally, the new footage takes place in two key areas: Tally’s lavish home environment, which serves as a kind of sanctuary for him, and in the areas of his work. Careful not to define what it is he does, we see someone who is as much a serious fan of his professional world as he is an active participant. Going through the archives of Vogue or The Met, we get to witnesses an encyclopedic mind in action, one that has seen a lot of fashion and understands where it all fits into a broader history. Tally is more self-deprecating, seeing himself as an “upgraded airline associate” or more simply “coffee, tea, or me.”

Yet Novack doesn’t let him diminish his own legacy or place in American history. This comes across in the numerous interviews that Novack has managed to secure, with an impressive list of talking heads that includes Marc Jacobs, Anna Wintour, Tom Ford, Will.I.Am, Valentino Garavani, Fran Lebowitz, Whoopi Goldberg, Diane von Fürstenberg, Sandra Bernhard, and various childhood friends and family members. (A memorable trip to Isabella Rossellini’s farm also gives us a cameo from two of the largest pigs we’re likely to see on screen).

Novack begins and ends her film around the 2016 US Presidential Election, and this anchor point gives the narrative about race in America a bittersweet bit of punctuation. Letting the cameras roll on the day after the election, we hear Tally at his most unguarded, as he speaks openly about his experience of being black and (for the first time in the film) gay in America. “It’s been rough,” he laments. Even so, with THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ANDRÉ, Novack gives Tally the platform he deserves and provides audiences with something more than soundbites and glamour.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2018 | US | DIR: Kate Novack | CAST: André Leon Tally, Marc Jacobs, Anna Wintour, Tom Ford, Will.I.Am, Valentino Garavani, Fran Lebowitz | DISTRIBUTOR: Madman Films (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 93 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 12 July 2018 (AUS)[/stextbox]