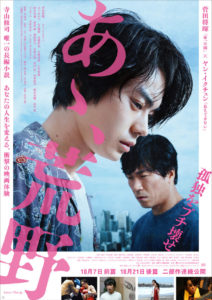

Following his feature debut A Double Life (2016), director Kishi Yoshiyuki has gone big. WILDERNESS (あゝ、荒野) – or more literally Ah, Wilderness – was originally released in Japan as two chapter film only weeks apart. Collectively it forms a five-hour epic about a pair of outsiders vying for a professional boxing career. However, to say this film is about boxing is like claiming Gone with the Wind is about a plantation.

Based on the novel by Shuji Terayama, the film begins in 2021 and immediately gets to the heart of the social and economic issues that contemporary Japan has been grappling with. Suicide rates are at an all-time high. Social welfare policies are inadequate to handle a crumbling system. Violent and explosive anti-government protests rule the streets. Against this backdrop, two loners are drawn into the same boxing gym by half-blind trainer Horiguchi (Yusuke Santamaria).

Shinji (the prolific Masaki Suda) has just been released from a juvenile detention centre, and thirsts for vengeance against a past violent encounter with Yuji Yamamoto (Yuki Yamada), who has become a boxer in the intervening years. His polar opposite is Kenji (Yang Ik-June), an extremely shy barber with a speech impediment. At its heart, this film is about the connection these “losers” find through the sport and a way back into the world.

The extended running time allows us explore their backstories in a way few other films accomplish. After all, this is the equivalent of a 6 or 7 episode mini-series. Takehiko Minato and Yoshiyuki Kishi’s screenplay draws out Kenji’s abusive father figure, and his later homelessness. Similarly, we discover that the suicide death of Shinji’s dad is central to his own mental health and outward aggressions.

As the second part transitions into 2022, the time spent with the characters is even more introspective. It works because we already have this solid base to build on, and cinematographer Kozo Natsumi is allowed to linger on boxing matches as the film builds to an inevitable series of confrontations.

In this hyper (and occasionally toxic) environment of masculinity, there are some issues to be had with the representation of women in the film. The three primary depictions of female characters come in the form of prostitute Yoshiko Sone (Akari Kinoshita), Kenji’s manipulative mother (Yoshiyuki Kishi), and Keiko Nishiguchi (Anna Konno), the downtrodden partner of activist Keizo Kawasaki (Kou Maehara).

Surreal pieces of performance art, led by Keizo Kawasaki, doesn’t always gel with the other material, but the avant garde nature (combined with the length) is reminiscent of Sion Sono’s work (particularly Love Exposure).

“Nowadays,” one character cynically laments in the second part, “death is a bigger business than life.” He’s speaking specifically about a wedding shop being replaced by a funeral home, but it’s perhaps the most biting indictment of the socio-economic environment in present day Japan. It’s hard to know if Yoshiyuki is leaving us on a note of optimism or not, but he’s certainly tapped into some of the biggest issues on the road to the future.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2017 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Yoshiyuki Kishi | WRITERS: Takehiko Minato, Yoshiyuki Kishi (Based on the novel by Shuji Terayama) | CAST: Masaki Suda, Yang Ik-june, Yuki Yamada | DISTRIBUTOR: Fantasia International Film Festival (Canada) | RUNNING TIME: 304 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 22 July 2018 (Fantasia) [/stextbox]

2017 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Yoshiyuki Kishi | WRITERS: Takehiko Minato, Yoshiyuki Kishi (Based on the novel by Shuji Terayama) | CAST: Masaki Suda, Yang Ik-june, Yuki Yamada | DISTRIBUTOR: Fantasia International Film Festival (Canada) | RUNNING TIME: 304 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 22 July 2018 (Fantasia) [/stextbox]