Following festival favourite The Mohican Comes Home, director Shûichi Okita returns with a portrait of the final days of Japanese Western-style painter Morikazu Kumagai. His vivid colours mixed with a deceptively simple style is winkingly referenced in an opening scene in which Emperor Showa (Yoichi Hayashi) enquires about the age of the child who painted the piece he’s examining.

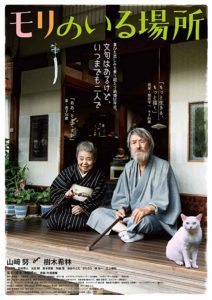

We are introduced to the 94-year-old Kumagai (Tsutomu Yamazaki) in his garden, intently staring at ants. Like the man himself, the film rarely leaves the surrounding landscape, allowing both Kumagai and the audience to deeply examine the nature he has ensconced himself in. This has been the routine he and his wife Hideko (Kirin Kiki) have followed for 30 years, welcoming a series of visitors that include the couple next door, a photographer, and a man wanting a sign painted.

Structured as a series of long takes, Okita’s screenplay isn’t so much concerned with factual accuracy as it is with capturing the playful mood of the artist’s work. Kumagai is endlessly fascinated with everything from insects to the plants in the small (yet somehow infinite) confines of his garden. “A genuine wood spirit or a hermit sage,” says the photography crew, although Okita’s film laughs this off as the eccentricities of an artist who thinks on a different level to us mere mortals.

The closest Okita comes to developing any drama at all is the construction of a condo overlooking Kumagai’s garden. Protest signs fill the streets, while Kumagai simply ponders what will become of the pond he’s been digging for decades.

In a film that has been liberated from a traditional narrative, or any at all, veteran actor Tsutomu Yamazaki is free to spend measured moments disappearing into Kumagai. The incomparable Kirin Kiki, who recently announced her retirement from cinema, exudes saintly composure and tolerance as Hideko. The pair bring their considerable comedic subtleties to a film filled with sly movements and winking humour.

Ridiculously charming, Okita paints his own portrait of an artist that would put off the chance of eternal knowledge to remain in his own backyard paradise. Like one of Kumagai’s works, you can appreciate the intricacies of MORI, THE ARTIST’S HABITAT (モリのいる場所) while observing it with a childlike awe. You may not learn anything biographical about Kumagai, but Okita nevertheless taps into exactly why the renowned painter’s work is remembered.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Shuichi Okita | WRITERS: Shuichi Okita | CAST: Tsutomu Yamazaki, Kirin Kiki, Ryo Kase | DISTRIBUTOR: Nikkatsu, Japan Cuts (US) | RUNNING TIME: 99 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 25 July 2018 (Japan Cuts) [/stextbox]

2018 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Shuichi Okita | WRITERS: Shuichi Okita | CAST: Tsutomu Yamazaki, Kirin Kiki, Ryo Kase | DISTRIBUTOR: Nikkatsu, Japan Cuts (US) | RUNNING TIME: 99 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 25 July 2018 (Japan Cuts) [/stextbox]