War. What is it good for? Decades worth of quality cinema, that’s what. Nobuhiko Obayashi has been a fixture of Japanese cinema for the last half century or so, exploring and experimenting with the form. Forty years on from House, his most famous film outside of Japan, Obayashi maintains his distinct visual flourishes within the context of a sweeping saga that gets to the heart of a national identity.

Based on the 1937 novella by Kazuo Dan, Obayashi and Chiho Katsura’s screenplay frames the doomed lives of a group of teenagers living in a pre-Second World War coastal town through the “wrong end of a telescope.” Stylistically this means the aesthetic of a black and white silent film, right down to the speed-ramping and exaggerated expressions of the period.

As we’re introduced to the 17-year-old hero Toshihiko (Shunsuke Kubozuka) and his classmates, the style changes to a widescreen technicolour, although it retains the artificiality of rear-projection and animated cherry blossoms. It signifies a people and a country on the cusp of an idealistic change, one that we know is destined to lead Japan down a very different path than they expected.

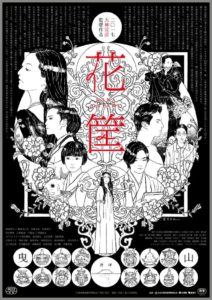

The deliberately archetypal characters that surround Toshihiko – the enigmatically surly Kira (Keishi Nagatsuka), class clown Aso (Tokio Emoto), love interest Mina (Honoka Yahagi) – serve to support and emphasie Obayashi’s construct. As he makes his way through a century of Japanese, Hollywood and European cinema techniques, including at least one direct reference to Nosferatu, he is also telling the story of his nation’s difficult relationship with history, war, and peace.

Being a Obayashi film, one shouldn’t be surprised to find the surreal elements creeping in early and becoming more prominent in the back half of the film. “It’s like a half-awake dream,” Mina exclaims, and she’s not wrong. A giant cut-out moon frames her in one scene. In another, children playing at war in one moment are laying in their own killing field in the next. The second hour of the film is very much built around a series of festivals, including an emblematic Red Snapper, and it feels like it was almost lifted straight out of a Japanese film of the period.

Obayashi doubles down on the time-skipping motif as the country heads into war, repeating several key scenes over and over throughout the film. It eventually coalesces in a choatic overlap of all the recurring memes in the film – soldiers, parades, elderly prostitutes, naked horseback riding, the ocean, an island. Each has its own symbolism, but it would be folly to look for a literal interpretation of the abstract. Instead, it’s a collage of moods that is about people and war, but decidedly against the latter.

Over the coda of a bright field illuminated further by the animated cut-out of the A-Bomb, on-screen text tells us that “Japan lost the war and peace returned. We shouldn’t start another war to keep the peace.” Which is where the crux of Obayashi’s 3-hour film, one that dares you to questions the lessons culture has indoctrinated you with.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2017 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Nobuhiko Obayashi | WRITERS: Nobuhiko Obayashi, Chiho Katsura | CAST: Shunsuke Kubozuka, Shinnosuke Mitsushima, Keishi Nagatsuka | DISTRIBUTOR: Japan Cuts (US) | RUNNING TIME: 169 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 29 July 2018 (Japan Cuts) [/stextbox]

2017 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Nobuhiko Obayashi | WRITERS: Nobuhiko Obayashi, Chiho Katsura | CAST: Shunsuke Kubozuka, Shinnosuke Mitsushima, Keishi Nagatsuka | DISTRIBUTOR: Japan Cuts (US) | RUNNING TIME: 169 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 29 July 2018 (Japan Cuts) [/stextbox]