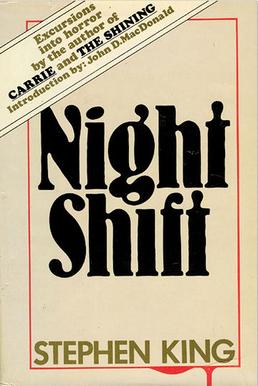

Welcome to the feature column that explores a decent number of Stephen King’s books in the order they were published!

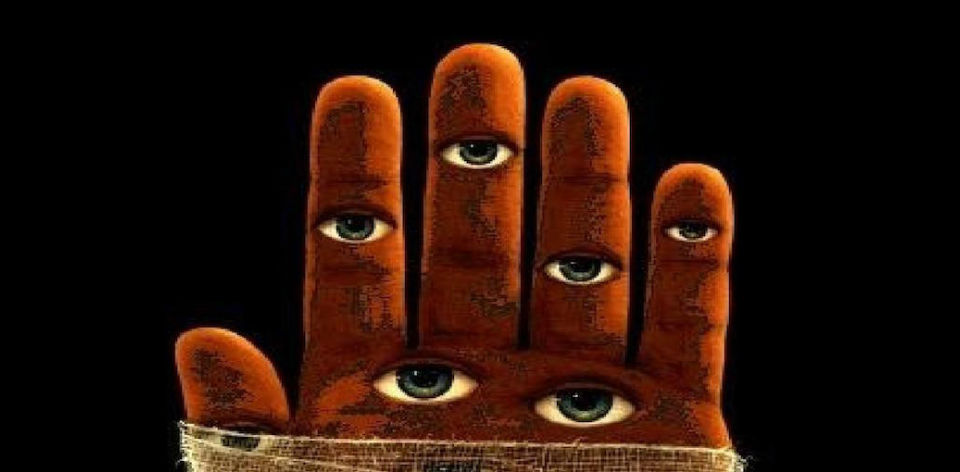

This collection of short stories came out at a time when Stephen King was making a mark and had clearly defined where he was going as a writer. After all, Carrie, Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and The Stand are a fairly impressive opening salvo for any author. So the stories here – covering a publication period of 1968 to 1977 – show us exactly how King got to that point, and where he would be going next.

The Lovecraftian “Jerusalem’s Lot” opens the book, an epistolary approach in which the reader and writer come to a dawning horror about what actually lives in ’Salem’s Lot. Even if you’ve not read King’s 1975 novel (and you should: it’s brilliant), the slow building tension draws you into historic Maine, and leaves us with a winkingly clever final beat that sets up the bigger story. King’s fascination with the world continues in “One for the Road,” a shockingly modern indirect sequel to ’Salem’s Lot. As the penultimate story in this collection, it’s bloodcurdling because of what we don’t see and hear. Like the narrator, you may be left with lingering memories of this tale for many years to come. King would return to some of that world years later in Wolves of the Calla (2003), the fifth Dark Tower book.

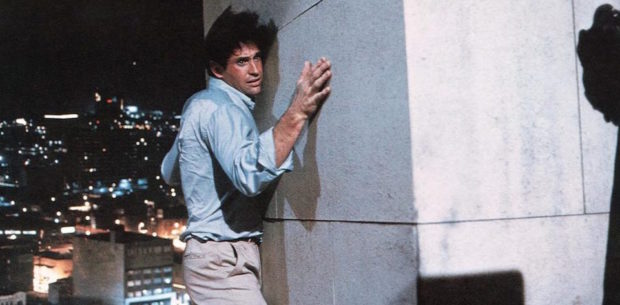

“Graveyard Shift” takes the rats in the wall of “Jerusalem’s Lot” more literally, and its easy to see why Ralph S. Singleton could turn this into a schlock horror film in 1990. In fact, a number of the stories here were adapted to the screen. It’s Stephen King: of course they were. “Quitters Inc” and “The Ledge,” for example, both formed part of Cat’s Eye (1985), and are both gripping in their moment to moment horror. It’s unfortunate that both stories have an unhealthy fascination with torturing or baiting the protagonists’ wives in order to achieve their aim.

On that note, it’s hard to ignore the casual homophobia, sexism, and racial attitudes that were very much ‘of the time.’ It would be a stretch to call out King for being prejudiced in any way, but those elements are so common in this era of King that it does make reading them in the context of 2018 difficult. Most of these attitudes come from the internal monologues of less than honourable characters, such as the ambiguously motivated character in “The Boogeyman” who can’t fathom waking up and finding out that his son is “a sissy,” for example.

Some of the stronger stories are where King sticks to some basic horror tropes. “The Mangler” sees a laundry machine turn horribly evil and become possessed by a demon. Similarly, “Trucks” is about killer…well….trucks. Holed up in a service station, a small group of survivors contemplate what to do next, and it’s vaguely reminiscent of the format that King would use a few years later in “The Mist” short story and, of course, Christine (1983). As the fuel hungry trucks make the humans choose between survival and enslavement, I imagine this is exactly what the origin story of Disney-Pixar’s Cars looks like.

“Children of the Corn” feels the most complete, filled as it is with a slow-building tension that could have sustained an entire novel. Although how it spawned 10 TV and film adaptations and sequels is beyond me. “The Lawnmower Man” similarly got a film adaptation but is completely different from the virtual-reality focused film that was released in the 1990s.

Yet where we really see the range of King’s writing is in the stories that teach us to expect the unexpected. The nostalgic “Strawberry Spring” takes on a darker turn as the Twilighty Zone vibe grows. “I Know What You Need” and “The Man Who Loved Flowers” both begin with romance tropes before subverting our desires for the characters. The final story, “The Woman in the Room,” is a heartbreaking piece about a man’s decision to euthanize his terminally ill mother.

Just as the Bachman persona allowed King a chance to explore different styles without the burden of his bestselling name attached to it, these short stories – originally published in Cavalier, Ubris, Penthouse and other magazines – gave both the constant writer and constant readers the opportunity to see different shades of horror from the high-concept to the everyday.