Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

A Bond novel written entirely from the perspective of a woman? It’s a good thing Twitter didn’t exist in 1962. The tenth Bond novel is something of an anomaly in Fleming’s oeuvre. It’s widely known that this is his shortest Bond novel and the sauciest one to boot, but it’s also told in the first person from the point of view of Viv Michel. It’s positively progressive for a writer who was a success, according to The Evening Standard, because of “the things that make Bond attractive: the sex, the sadism, the vulgarity of money for its own sake, the cult of power, the lack of standards.”

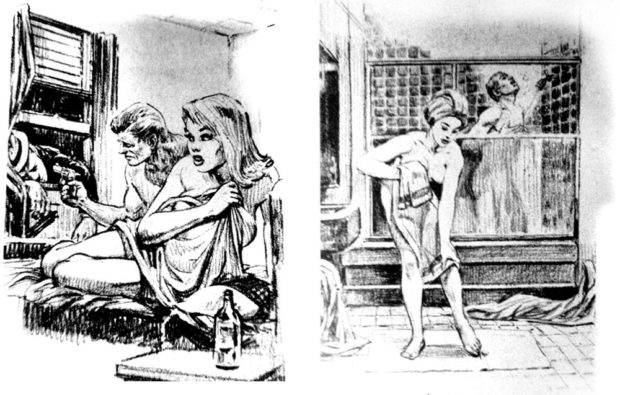

Split into three sections – “Me”, “Them” and “Him “ – Vivienne “Viv” Michel recounts her misadventures with jerky men and the decision to take off on a Vespa scooter before getting caught up in a motel being tortured by cruel gangsters. Bond doesn’t turn up until the last third of the book, offering an alternative model of a man for Viv and a convenient white knight to get her out of a jam. Through it all, Fleming consistently portrays Viv as a self-made woman, owning her own sexuality and dictating the direction of her own narrative. Viv matter-of-factly talks about her abortion in Switzerland, over a decade before Roe V Wade in the United States.

Which is not to say that the book is a feminist reader. Viv Michel has a lot in common with the previous Bond Girls: she’s broken in some way, only here we get to see how the damage was done. Fleming might prove that he can write a female point of view convincingly, but he also runs his heroine through the ringer: one of Viv’s lovers “took me fiercely, almost cruelly.” The middle act is basically torture porn as Viv is beaten repeatedly by her captors. In a typical Flemingism, Viv comments that “All women love semi-rape. They love to be taken.” Are you cringing as much as I am?

Yet in Fleming’s own way he is depicting the challenges of a woman in a male dominated world, a somewhat clumsy commentary on the normalisation of rape culture that lead to the popularity of his fiction. Douglas Kennedy notes in the introduction to the 2012 edition of this book that Viv “realises true liberation involves not wanting to conform to the gender roles most women of her generation were forced to play.” I’m not entirely convinced.

So, if The Spy Who Loved Me stumbles it’s not because of its narrator but in the way Fleming does her a disservice. It’s not the first time that Fleming had handed the story over to other characters before introducing Bond. From Russia with Love takes over 100 pages to introduce Bond, instead giving us time to discover SMERSH executioner Red Grant. Five books later and Fleming is in even less of a hurry to get to 007. Even so, Bond is basically still Bond when he appears. Viv, despite of her progressive qualities, is mired for much of the book in melodrama and a tragic narrative. Even with all of Viv’s self-determination, it’s only the arrival of Bond that ultimately saves her.

Unsurprisingly it’s the final act of the book (“Him”) that most resembles a traditional Bond. There’s a story within a story of Bond’s adventures that led him to Viv, and traditionalists would probably prefer Fleming had told that off-page story instead. (There’s a challenge for you fan-fic writers, if you’ve not done so already). Fleming’s casual dismissal of these adventures probably speaks to his headspace at the time: his legal woes around Thunderball, failing health (he had a heart attack during the trial), and problems with his relationship with his wife inform his attitudes to the spy. The book definitely reads as though Fleming was working through some serious stuff.

Fleming tried to halt future publication of this book, displeased with the results and only handing the naming rights over to film producers. (The eventual film did not use any of the plot details, although elements of the ‘Horror’ character find their way into Jaws). There’s some pretty questionable moments in here, but it’s far from a complete disaster. Combined with the short stories of For Your Eyes Only, and the second last Bond novel released in Fleming’s lifetime, it’s demonstrative of a writer who was willing to experiment with style but feeling shackled by his creation.