Cormac McCarthy’s BLOOD MERIDIAN, OR THE EVENING REDNESS IN THE WEST was a marked departure for the author. Following a quartet of books that took place in the Appalachians, including the publication of Suttree after 20 years in the works, McCarthy’s fifth book shifts to the Southwestern United States and goes straight for the bloody jugular. It is not simply an important book in the writer’s career but a towering achievement in prose, exploring the very nature of human violence and goodness in a world filled with darkness.

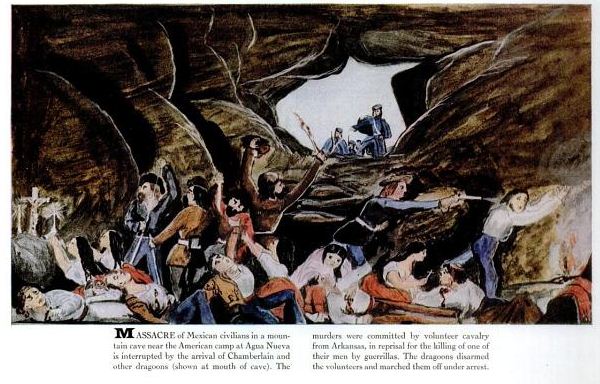

Based on the exploits of the Glanton gang, an actual historical group of scalp hunters who operated on the Texas-Mexico border in the mid 19th century, McCarthy takes inspiration from alleged gang member Samuel Chamberlain’s memoir – the sadly out of print My Confession: Recollections of a Rogue – to tell the story of “the kid.” While Captain Galnton is the nominal head of the gang it is the highly educated, completely bald, and towering figure of Judge Holden who truly rules the roost. The inevitability of their relationship is fated in the stars: we are told that the kid was born on the night of the Leonids meteor shower of 1833: “God how the stars did fall.“

Packed inside a dense structure, McCarthy frequently uses archaic language, eschews conventional punctuation and quotation marks, and has long passages written entirely in Spanish. McCarthy forces you to consider each word in turn, take a deep breath (and maybe a cleansing shower) before plunging your eyes back into the inky blackness of his text. McCarthy, via the Judge, addresses this relationship the reader might have with the text: “Words are things. The words he is in possession of he cannot be deprived of. The authority transcends his ignorance of their meaning.” Which is how one might feel after a chapter or two of the novel: regardless of literal understanding of every single archaic phrase, the weight of each sentence lingers long after it has been read. To this end, McCarthy has included brief synoptic headings at the start of each chapter, themselves an archaic form of writing. It allows the reader to worry less about the narrative and more about the flow of the language.

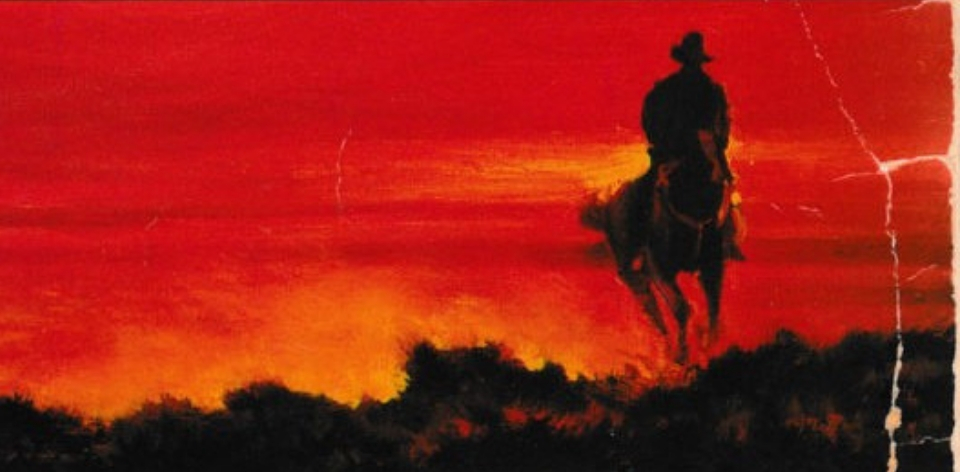

The technique might also speak to the fated inevitability of the more gruesome aspects of this American horror story. BLOOD MERIDIAN is an often nightmarish and surreal trek into the hearts of darkness. The violence is relentless in its escalation. Steven Shaviro argues that McCarthy “sings hymns of violence, its gorgeous language commemorating slaughter in all its sumptuousness and splendor.” It’s a fair argument in a book that features trees of dead babies, graphic depictions of slaughter, regular scalping, extreme castration, and infanticide. McCarthy is challenging us at every turn, eviscerating the myth of the noble cowboy, and ultimately leaving us numb to the waves of bloodletting. In the wake of infants being swung against rocks until they burst in a “bloody spew,” the deepest horrors of the final act seem tame in comparison.

Which makes the ambiguous ending all the more powerful. As McCarthy has done in his later works, most notably No Country for Old Men, the fates of key characters happen off page. The fate of the the kid at the hands of the Judge is never spoken aloud, only inferred through the actions and language of the bystanders. The presumptive psychosexual consumption of the anti-hero by the primary protagonist is monumental in its meaning and yet it is written in a way that could be see as a coda or an aside. It too is just another act in a timeless cycle.

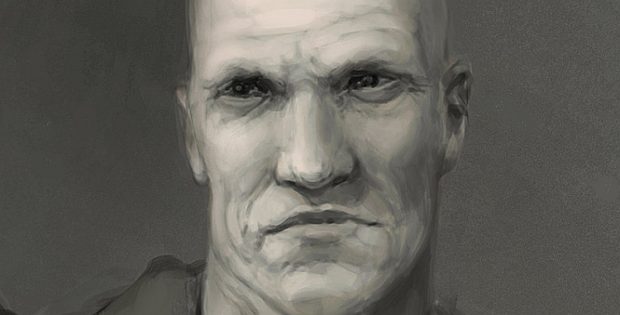

The Judge – an enormous, pale, and mystically depicted figure – is not so much the embodiment of evil as, according to several critics, a servant of a creative and destructive force. “What exists, he said. Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” His fatalistic approach to existence drives much of the violence in the book, along with the notion that war is a god. His vision of America is one born to war, defined by war, and it’s inevitable future is an endless war. “It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures…War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him.” Even more than his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Road, McCarthy’s idea that the future of humanity is war is one of his most nihilistic.

The grim interpretation of creation is just some of the religious imagery etched into every aspect of the book. The Judge, initially introduced as a kind of revivalist preacher, regularly involves the group in theological debates. He has been compared to a god, a devil, a creator, a gnostic archon, a trickster and so on. Yet perhaps it’s a debate – the existence of goodness in a world full of evil deeds – that gnostic humans cannot possibly comprehend. “A man’s at odd to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with. He can know his heart, but he don’t want to. Rightly so. Best not to look in there.” McCarthy confirms the unattainability of this knowledge in the final pages as a passerby, seeking to view the fate of the kid, is told as much in a paraphrased way: “I wouldn’t go in there if I was you.”

It’s impossible to convey the impact that BLOOD MERIDIAN has had on me over the years. This is about my third read-through and I’m still finding large pieces to unpack, and will probably continue to do so as the years go by. It’s an even bleaker journey than I remember, and like the Judge it will endure well beyond the lifespan of anyone reading these words. “His feet are light and nimble. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die.”