Welcome to the feature column that explores a decent number of Stephen King’s books in the order they were published! (More or less!)

This month, the Club skipped forward 8 books after Firestarter in anticipation of the release of the 2019 film adaptation of the cemetery with the pets and such. We will (kind of) return to regular programming in April with a double-feature of Danse Macabre and On Writing.

Stephen King has killed a few people in his time. Literarily speaking, of course. So, it’s totally apt that at the most prolific point in his career he chose to meditate on grief and loss, those necessary and hard to quantify elements that follow in death’s wake.

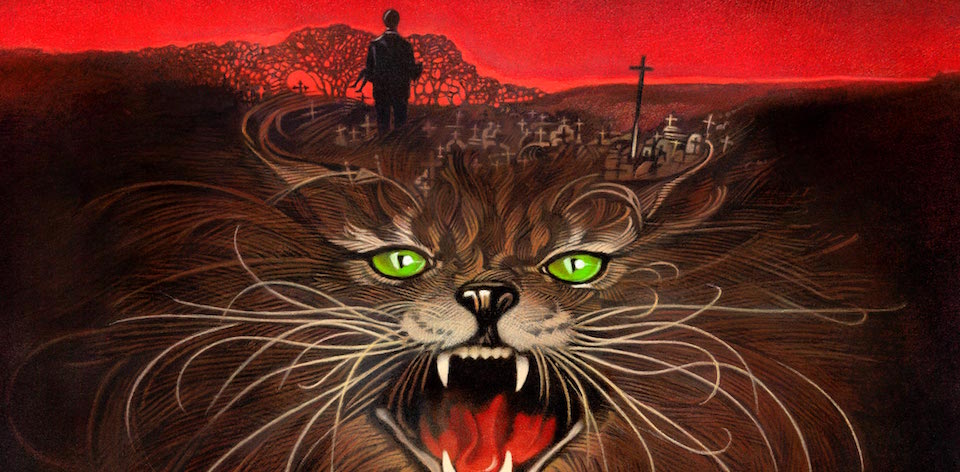

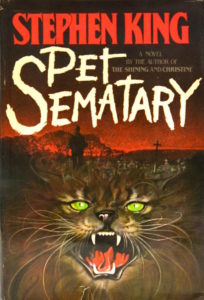

PET SEMATARY is unquestionably a horror story, and arguably one of King’s most unnerving to date. Indeed, in the introduction to the book the author regards it as “the most frightening book I’ve ever written” and initially ponders whether or not he had gone “too far.” Inspired partly by the death of his daughter’s cat, and “thinking the unthinkable” after a near-death miss with his youngest son, this is possibly one of the rawest pieces of fiction King has constructed.

On the surface, we are in familiar territory. Maine, of course, but also thematically following a thread that’s been present since at least ’Salem’s Lot. As doctor Louis Creed moves his family from Florida to the remote Ludlow home, there’s also shadows of The Shining that are hard to…overlook. (Sorry. I’m so sorry). It’s about a family dynamic shattered by something sinister, but how that fear also infects everyday life.

On the surface, the Creeds seem like a perfect family unit. A doctor for a father, a loving wife, and two adorable children. Louis shares a friendship with his elderly neighbour Jud, who also acts as a kind of surrogate father figure. Without going into unnecessary spoilers, tragedy besets the clan repeatedly, like a hammer. Through this we see how each of them cope in turn, including the Creed’s eldest child Ellie and her maternal grandparents. The presence of the latter also indicate that cracks in their happiness didn’t appear when grief took hold, it merely revealed the ones that were ready to gape open.

Through this, King finds something close to a catharsis not just for the feelings he was working through, but perhaps for anybody else suffering from related grief. Grief and loss are described in many way: “like some gray matron from Ward Nine in purgatory” or “like a massive tooth extraction. There was numbness at first, but even through the numbness you felt pain curled up like a cat swishing its tail, pain waiting to happen.” It’s relatable because it speaks to the non-linearity of the grieving process that goes beyond the Kübler-Ross model. It’s frightening because it’s a monster that lurks in the corners of one’s periphery, and you’re never quite sure when it will appear. Church, the ill-fated family cat, acts as a kind of avatar for grief in a way.

Yet King is right in his contention that this is one of the scariest things he has written. Like The Shining, there are demons both literal and figurative. The mythology around the titular cemetery (or Sematary if you like) underpins the ghost story element, but it is only the fuel for the true darkness. As Louis’ obsession grows, we are just as hooked but whatever he is planning to do next as anything that might find its ways through the encrusted earth. He is Jack Torrance wielding his loss like a weapon, pushing his family away so they don’t see the true depths of his addiction.

Filled with the kind of foreshadowing that King excels at, there is a certain sense of inevitability to PET SEMATARY . In some cases, King flat-out tells you what is going to happen chapters or mere pages ahead of time. Nevertheless, as the final 30% of the book melts into a relentless spiral of inky blackness, this is a thematically difficult book told in the most engaging way possible. Or as Tabitha King was reported to remark: “Awful, but too good not to be read.”