Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

The 12th Bond book has the distinction of being the last published during Fleming’s lifetime, and it comes with a pervading sense of ennui. The third and final chapter in the so-called “Blofeld Trilogy,” Fleming seems just as interested in exploring Bond’s personality and breathing new life into him as he did a dozen books earlier. Of course, Fleming would die only months after the release of this book, so in many ways it is also a swansong.

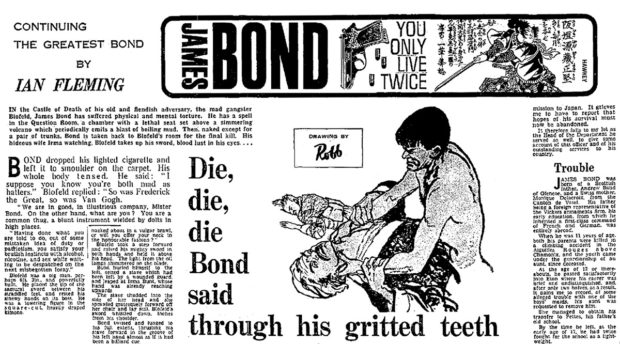

Picking up about nine months after the events of On Her Majesty’ Secret Service, Bond is still feeling a bit down about that whole unpleasantness of his wife being killed by Blofeld. Stiff upper lip, Bond! Can’t let the side down and all that. It’s a morose Bond we’ve never seen before, and as Raymond Benson points out in The James Bond Bedside Companion, not even Vesper Lynd left Bond this forlorn. It’s a curious treatment of depression, seen through Fleming’s macho 1960s lens as a temporary malady. “He’s slowly going to pieces,” laments M. “I’ve got not room in this Section for a lame-brain. Whatever his past record or whatever excuses you psychologists can find for him.” Looks like someone needs to go to his compulsory HR training.

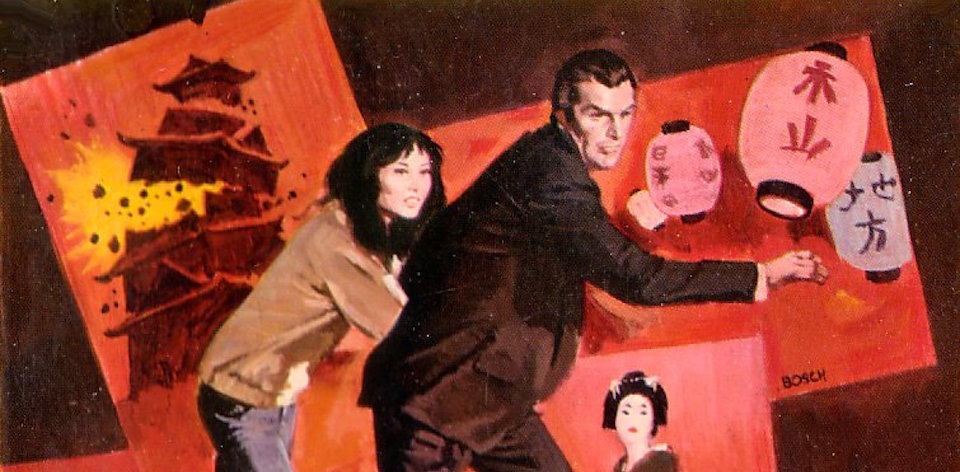

Bond – or should I say “Bondo-san” – spends most of this book in Japan, on an “impossible mission” that slowly becomes one of rebirth, redemption, and revenge. Bond is something of an Imperialist cultural tourist at first, turning his nose up at almost everything traditional in the country. “What a daft set-up,” he’s heard to remark at one point. Some of this seems like perfectly reasonable responses to being told suicide is a societal norm, at other times its downright belligerent. His counterpoint in ‘Tiger’ Tanaka, the head of Japan’s secret intelligence service, doesn’t hold back from testing him though, holding an equally pointed mirror to the crumbling Britannia.

Having been witnessed Fleming construct his hierarchy of races (Live and Let Die, Dr. No, “Quantum of Solace”), and been less than kind to Koreans in Goldfinger, I naturally had apprehensions about how he might portray Japan. The rich cultural tapestry of Japan is often misunderstood by foreigners, and Fleming offers us Kissy Suzuki as an ambassador. Despite her Bond Girlish moniker, her presence as an ama (or “sea woman”) adds a cultural layer not seen in Fleming’s infantilised versions of women while slightly reminding us of Honeychile Rider in Dr. No. Kissy is no “bird with a broken wing” as he is fond of saying. Similarly, when Bond himself isn’t outright dismissing it, Japan is treated with a kind of delicate reverence.

Of course, while I was worrying about the depictions of the Japanese by the notoriously problematic Fleming, I got completely blindsided by a couple of unprovoked slights on Australians. Our secret service was in its relative infancy in 1964, at least when compared with MI5/MI6, and is represented by “Dikko” Henderson, a brash and loud-mouthed character who only really appears in the first few chapters. Of course, it’s long enough for him to tell us that “The bloody Japs do everything the wrong way round. Read the old instruction books wrong, I daresay.” Ok, so maybe not entirely reverential.

Mind you, this is a character who talks about “cock tax” and drops in a racial slur about Aboriginals and voting rights only pages later. Until 1967, the Australian Constitution prohibited Indigenous Australians from being counted in the population and thus voting. So, his opinions were actually part of mainstream discourse in the 1960s, showing that Fleming was still abreast of global politics at a state level. Nevertheless, on behalf of most Australians, I would like to disavow the actions of Richard Lovelace “Dikko” Henderson. His file is now closed.

Fleming sets up the gripping finale as something of a Reichenbach Falls for Bond and Blofeld, an epic fight that sees a sword-swinging Blofeld attack 007, who is wielding a wooden staff. The visceral end for one of the characters puts a full-stop not only on the saga that had been building since Thunderball, but on this era of Bond. Indeed, if no future Bond books had been published it would have been a fitting end for the character as well. There’s even a chapter written like a (premature) obituary, detailing Bond’s early life and details hitherto undisclosed. It’s perhaps only the coda that lets YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE down, with its rapid slide into sentimentality and sex toys (seriously), that leaves the book on a weird note.

The ripple effects of YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE continue to have impact as the years go by. Sean Connery’s portrayal of the character in the 1967 film adaptation solidified the narrative in the public’s mind, even if it did include the unfortunate sight of the Scotsman in Japanese drag. Raymond Benson would write a sequel of sorts years later for Playboy called “Blast from the Past,” picking up on a thread that was left provocatively dangling in that odd coda: Bond’s son, James Suzuki. In the end, it’s just a solid classic Bond, complete with a lair and a torture device, albeit one that has a far more leisurely approach than we’re used to now.