Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a structured reading (and in some cases re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

As a casual fan who has read the ‘popular ones’ several times, this series is an attempt to explore Tolkien’s grand legendarium chronologically. Hundreds of scholars have already done deep reads, so this is just me trying to better understanding of Tolkien’s myths and legends by seeing them in context. Or to just point out cool stuff I liked along the way. Legendary spoilers abound.

The tales of the Elder Days, or the First Age of Middle-earth, remain a daunting task to readers who just want to enjoy sagas of Jewels and Rings. Yet there is much to be found in J.R.R. Tolkien’s three Great Tales of the era: Beren and Lúthien, the Children of Húrin, and the Fall of Gondolin. While Tolkien fans have been all over them for years, Tolkien’s son and keeper of the flame Christopher Tolkien cites their “repute as strange and inaccessible in mode and manner” as keeping them from more mainstream recognition.

THE CHILDREN OF HÚRIN, published as single narrative “with a minimum of editorial presence” by Christopher in 2007, aims to correct this inaccessibility. The basic narrative could be found in the previously published works Unfinished Tales (1980), The Book of Lost Tales (1984), as an incomplete epic poem in The Lays of Beleriand (1985), and, of course, The Silmarillion (1977). It’s the latter that serves as the best introduction to this text, where we learn of the evil intent of Morgoth and the curse he places on all of Húrin Thalion’s kin.

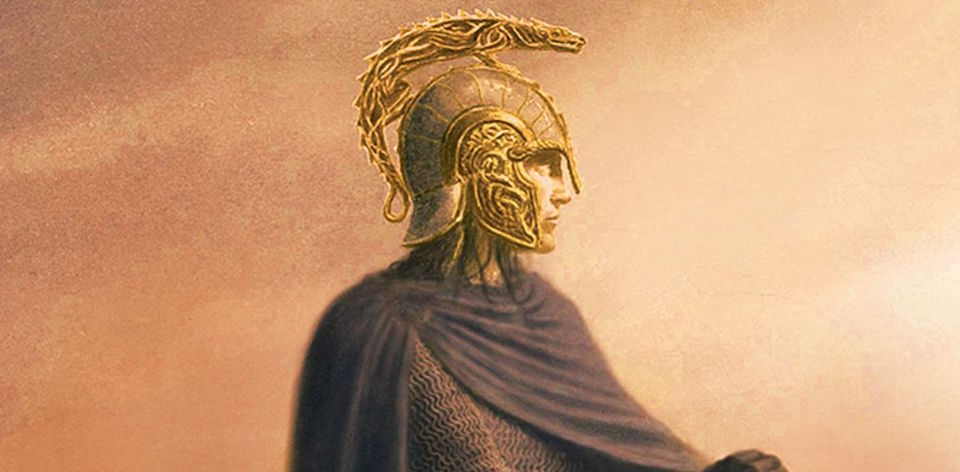

Where The Silmarillion is a broad brush stroke of the rise and fall of an age, THE CHILDREN OF HÚRIN represents a deep dive into the lore. The principal story follows Túrin, son of Húrin, who is sent to the Elf-realm Doriath for protection during his father’s imprisonment by Morgoth. There he is more or less adopted by King Thingol, accidentally causes the death of the Elf Saeros, flees to escape a perceived prosecution, joins a band of outlaws in the wild, and faces Morgoth’s servant Glaurung, a dragon who manipulates the fates of Túrin and his estranged sister Nienor.

If Beren and Lúthien is one of Tolkien’s most romantic stories, then THE CHILDREN OF HÚRIN might be the most tragic. Like many of the legends that Tolkien was inspired by – Sigurd the Volsung, Oedipus, and the Finnish Kullervo are cited in a letter to Milton Waldman “for people who like that son of thing, though it is not very useful” – Túrin’s doom is a cursed one. Yet it’s hard to feel too sorry for the poor sod, as often it’s his own (in)activity and pride at crisis points that usually results in more harm to those around him. Gwindor, the valiant Elf who you might recall started the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, identifies this harsh truth: “The doom lies in yourself, not in your name.” After all, Turin takes on the name Turambar (meaning Master of Doom in the High-elven speech) for himself. It’s this ongoing tension between free will and predestination that thematically dominates the tale.

The book is at its most readable when it allows itself the time to linger on discreet moments in the saga. The chapters involving Mîm, a Petty-dwarf, are a curious mix of whimsy and adventure, and feel most like something that Tolkien would have written in and around the War of the Rings. The final chapters, in which Nienor realises that she has married and been impregnated by her brother and they all kill themselves, were apparently mostly written as a single entity by Tolkien. So, it’s unsurprising that these bits feel the most complete and congruous with the greater history of Middle-earth. Those bits that don’t feel as harmonious speak to the way in which the book was pulled together.

Tolkien had an almost complete version of this tale before abandoning it in 1957. Indeed, in a letter to Christopher Bretherton in 1964, Tolkien mentions that it was one of his earliest tales that underwent many changes over the years.

“The germ of my attempt to write legends of my own to fit my private languages was the tragic tale of the hapless Kullervo in the Finnish Kalevala. It remains a major matter in the legends of the First Age (which I hope to publish as The Silmarillion), though as ‘The Children of Hurin’ it is entirely changed except in the tragic ending.”

The extent of Christopher Tolkien’s involvement in the putting together of this text has been somewhat contentious. Arriving so much later than his father’s posthumous work, it’s staggering to think that there were enough unpublished scraps left to string something new together. In a lengthy series of introductions and appendices, Christopher maintains that his only contribution was the piecing together of “a continuous narrative from start to finish, without the introduction of any elements that are not authentic in conception.” Naturally, there’s undoubtedly the editorial equivalent of some Spakfilla in there too.

So Christopher Tolkien’s work is primarily that of an academic, editor, and occasional extrapolator. Yet as Kelly Grover points out, in her 2007 review for The Guardian: “For those who assert that even such well-intentioned tinkering amounts to little less than literary forgery, only an arid academic edition of the extant texts would have been acceptable.”

While there is a lot to process here, filled with incomplete fragments couched in archaic language, is a grand addition to the pantheon of British myths and legends. It’s a tale that’s filled with revenge, battles, incest, a dragon, an evil force somewhere in the north, and lots of principal character deaths. All in one volume. Your move, George R.R. Martin.

In the next instalment of The Read Goes Ever On, I’ll continue with the posthumous publication of the great tales of the Elder Days. The Fall of Gondolin, published in 2018, another of the original Lost Tales that formed parts of The Silmarillion. Like The Children of Húrin, it is edited and compiled by Christopher Tolkien.