Welcome to the feature column that explores a decent number of Stephen King’s books in the order they were published! (More or less!) Fair warning: there will be spoilers ahead.

“It came to Castle Rock again in the summer of 1980.”

There were two things I knew about CUJO before diving in. First and foremost is that it is about a dog. It also had the reputation for being a book Stephen King had little to no memory of writing thanks to a cocaine binge, as confirmed in his honest memoir, On Writing. Perhaps what was most surprising was how little of each were evident in the text, with King once again musing on the evil that humans do.

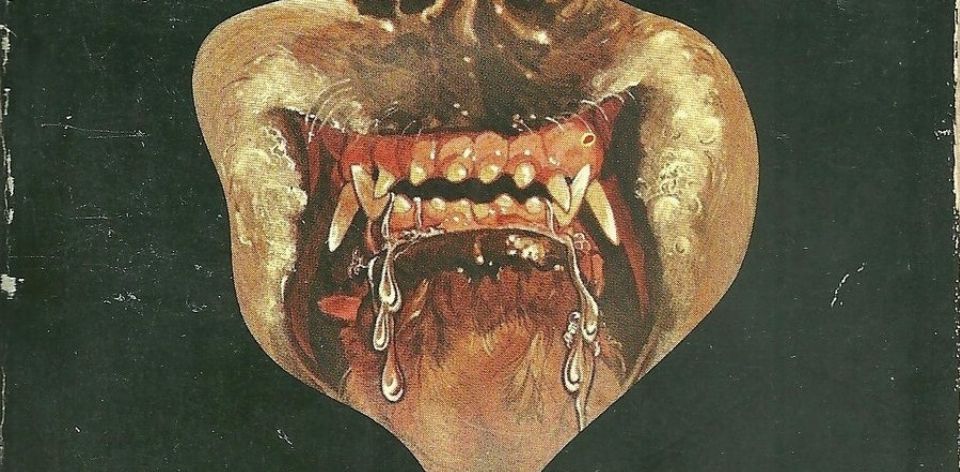

The titular dog, named after Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapper Willie Wolfe’s nom de guerre, is virtually a background character for much of the book. Much of the slow-building tension in the first half comes from his infection with rabies. King’s deft ability to get into the heads of characters extends to the animal kingdom, with several passages of the pre-rabid and violent St. Bernard interpreting external stimuli through the lens of his illness.

“He didn’t want to go home. If he went home, one of his trinity – THE MAN, THE WOMAN, OR THE BOY – would see that he had done something to himself. It was possible that one of them might call him BADDOG. And at this particular moment he certainly considered himself to be a BADDOG.”

The primary focus of the book is otherwise split between three groups of interconnected characters. Advertising men Vic Trenton and his partner Roger hit the road in a desperate attempt to save their company from failure. Roger has recently discovered that his wife Donna is having an affair with a sleazy and unhinged “poet” Steve Kemp. Then there’s young Brett Camber and his mother Charity, Cujo’s owners who are trying to get away from a violent father and husband. Meanwhile, Donna and her son Tad find themselves locked in a car and at the mercy of a rabid dog.

CUJO unquestionably rips along at a pace. There are no chapter headings or page breaks, perhaps the only structural indicator of King’s addiction-fuelled scribing. Flipping back and forth between characters, King creates the sense of a swirling maelstrom of events at times even when there is ostensibly little happening. As we approach the magic 70% mark of the book, which has consistently been the tipping point between good and great King, the remaining 30% melted away as my fingers struggled to keep up with the page turning.

For Constant Readers, CUJO also represents the starts of what would become King’s complex shared universe. It’s 1981, and the Richard Bachman output notwithstanding, King is seven novels and two collections of short stories into his career. While the towns of Jerusalem’s Lot and Castle Rock had made an appearance – and would be joined by Derry to form a Lovecraftian triptych in a few years – there was only the odd reference to hint that they were connected. From the opening line of CUJO, King plunges us straight into something familiar:

“Not long ago, a monster came to the small town of Castle Rock, Maine…He was not werewolf, vampire, ghoul or unnameable creature…he was only a cop named Frank Dodd with mental and sexual problems. A good man named John Smith uncovered his name by a kind of magic…”

King’s overt reference to the plot of The Dead Zone, and the later appearance of Sheriff George Bannerman, serves several purposes. A spiritual and perhaps even direct sequel to the 1979 novel, past tragedy in the town serves as a catalyst for the fear that continues to linger there. Tad is convinced that something sinister lurks inside his closet, and it’s just possible it is the “spirit” of Dodd himself. Yet it’s also a direct connection to a place that will forever be marred by human darkness. The tragedies that beset Castle Rock are human in making, and some of the most disturbing moments – such as Steve Kemp violently and sexually upturning the Trenton house in their absence – are motivated by nothing more than human failings.

Yet the same factors that give CUJO momentum may also serve to keep the audience at arm’s length. The constant leaping from character to character comes across as fractious and disjointed in some long passages, and the downbeat nature to the narrative is relentless. King’s strength has always been in his ability to build a world around his horror, but he almost forgets about his titular creature for chunks of the book.

King’s failing to remember writing CUJO is interesting, as it was published between two novels written by his alter ego Richard Bachman (Roadwork earlier that year and The Running Man in 1982). It’s almost as though he was taking an extended absence of leave from himself. Yet King would return to Castle Rock at least another half dozen times across novels and numerous short stories, and would eventually form the basis of a hit television series of the same name. So perhaps through the cocaine haze, King had inadvertently struck upon one of the doors to the Multiverse, a thinny in the Todash if you will. In fact, less than a year later King would publish the first book in the metafictional The Dark Tower saga.