Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

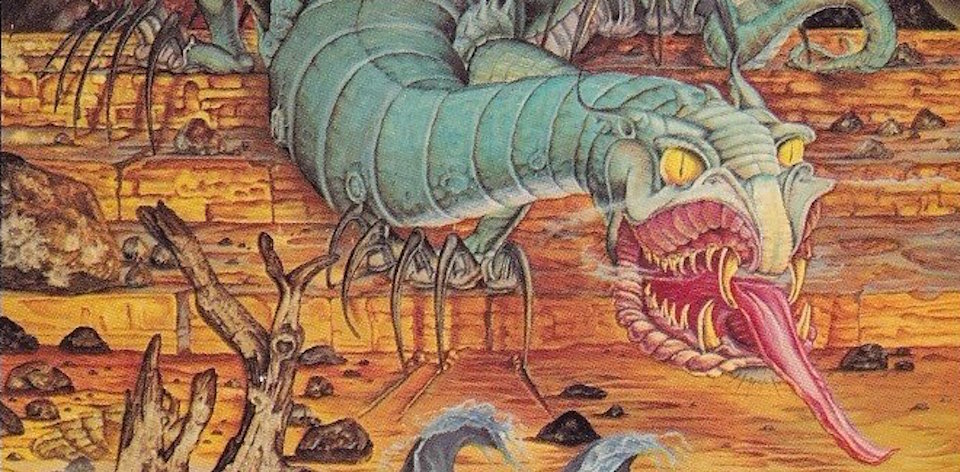

We’re deep into the weeds now, dear readers. If The Silmarillion was Tolkien’s heavily produced posthumous album, then the UNFINISHED TALES are the raw demo tapes.

Fully titled Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth, it’s a bit of an odd bird. First published in 1980, before Christopher Tolkien had completely gone through his father’s papers, it’s a collection of raw and incomplete story fragments and facts from the First, Second and Third Age.

The book is split into four distinct sections. In the first, we read of Tuor coming to Gondolin and the Narn i Hîn Húrin (or The Children of Húrin). Much of this material, or at least the broader story, will be familiar if you’ve read The Silmarillion or any of the standalone volumes from Great Tales. These are the most complete stories in the volume, evidenced by Christopher Tolkien going back into the well with these fragments almost 30 years later.

In the section covering the Second Age, we are (re)introduced to the island of Númenor via a detailed description. The story proper begins with the incomplete Aldarion and Erendis: The Mariner’s Wife, being the tale of the Sixth King of Númenor. The Second Age is known for being the least fleshed out of Tolkien’s mythology, and the story of Tar-Aldarion is one of the few (almost) complete tales that we have from this epoch. The semi-romantic tale may not rival Beren and Lúthien, but it puts a human face on the mysterious Númenoreans. (A map of the doomed island turned up in Amazon publicity for their upcoming series, so it might be worth paying attention to).

The rest of the Second Age section is no so much a narrative as a collection of essays, fragments, and chronologies. Some of this is quite literally names and dates of the Kings of Númenor in a dry biographical dictionary. The History of Galadriel and Celeborn is of more interest as even casual readers will reocognise one of those names. Christopher Tolkien’s style emerges here and stays for the rest of the book, weaving his father’s existing prose, notes, and essays in with his own attempts to reconcile inconsistencies with the appendices in The Lord of the Rings.

By the time we get to the Third Age tales, most folks will be on more familiar territory. Covering periods outlined in The Lord of the Rings appendices – and filmed in a compressed format at the start of Peter Jackson’s first entry – we learn a little more abut Isildur’s loss of the Ring and the subsequent hunt for its whereabouts just prior to Gandalf visiting Frodo in the Shire. There’s also some more detailed information about Sauron’s attempts to take Rohan during The Battles of the Fords of Isen.

Rounding out the volume is a trio of various bits and pieces that fill out the mythology. There’s an essay expanding on the Drúedain, a race of wild men; a manuscript made up of various documents about the Istari (the wizards Alatar, Gandalf, Saruman, Pallando, and good ol’ Radagast); and the The Palantíri – those seeing stones you probably shouldn’t grab hold of.

Like The Silmarillion, I found this one a bit of a tough read. Christopher Tolkien’s hands-off approach only changes the names from his father’s text for large tracts, with J.R.R. being in the habit of changing names in his drafts. There are parts in this section where I felt my eyes sliding off the page, as the carefully chosen words went in one eye and out the other. The later bits have a more fluid and accessible writing style. The subject matter, from Gollum’s torture to Sauruman’s pipe-leaf habits, are certainly more engaging than entire eras sailing past like so many Númenorean mariners.

I now wish

Tolkien in

that no

appendices

had been

promised.

a letter to

Rayner Unwin

in 1955

You have to come at this with a hunger for filling in the gaps between The Silmarillion and The Hobbit and beyond. In 2019, I’m probably more inclined to go down a wiki clickhole of names and dates than use this as a resource, but we have to think about this in context. When it was first published in 1980, its success influenced the launch of Christopher Tolkien’s epic 12-volume History of Middle-earth series (1983 – 1996), proving there was a hunger out there for this level of detail.

For serious Tolkien fans, there is a lot here. While the stories themselves might be fragmentary, Christopher Tolkien has painstakingly referenced this with alternate versions, background text, name variants, and a formidable index. Even the footnotes have footnotes. Some of this might be generously called “a bit much.” One section, for example, comes with the disclaimer that the “story depends for it full understanding on the narrative given in Appendix A.” Indeed, J.R.R. once wrote (in a letter to Rayner Unwin in 1955) that the appendices “in truncated and compressed form will satisfy nobody” unless you are “people who like that kind of thing.”

He adds that those who wish to enjoy his tales as an “’heroic romance’ only…will neglect the appendices, very properly.” I mean, he’s not wrong: large chunks of this feel like you’ve been bailed up in the corner of a book shop and told at length why the Sindarin word for ‘shield-fence’ has etymological ties to the Quenya word sandastan. Like I said: we’re in the long grass now.

Which is where most casual readers will find themselves with UNFINISHED TALES. In retrospect, I kind of wish I’d skipped this until I’d re-read The Lord of the Rings and its appendices. In fact, Christopher Tolkien suggests as much in his introduction, and yet boldly I marched on. Which was kind of the point: I wanted to know a bit more about Tolkien’s bigger legendarium before revisiting the classics, and boy did I get it.

In the next instalment of The Read Goes Ever On, I’ll head into something a little more familiar with The Hobbit. Finally: a book where I’ll understand more of the words!