There’s an old joke. Two elderly critics are sitting in a cinema, and one of them says “Boy, the films at this place are really terrible.” The other one says, “Yeah, I know, and such short runtimes.”

The deceptively low-key release of JOKER is ostensibly at odds with the fanfare that usually accompanies a comic book adaptation. Indeed, director Todd Phillips has described the film, which took out the top prize at the Venice International Film Festival, as “a way to sneak a real movie in the studio system under the guise of a comic book film.”

The hubris of that comment, one that both puts down the source material and its fans while claiming an elevation, seems to unironically get to the heart of the perceived societal denigration he and co-writer Scott Silver are possibly railing against in their screenplay. I say possibly because this is a film that casts its nihilistic web wide while tapping into the last dying angst of the middle-aged white man in America.

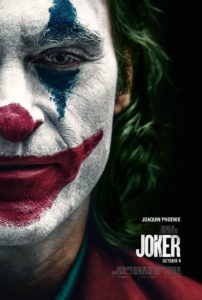

Set in an indistinct period reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s 1970s New York, we’re introduced to sad clown and aspiring comedian Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), who lives with his unsupportive mother (Frances Conroy) and works a variety of small jobs on the mean streets of Gotham City. A condition causing him to laugh spontaneously masks his inner pain, yet after being repeatedly downtrodden an act of violent retaliation is the spark that ignites a city.

It’s clear from the beginning that we are not meant to trust what we are seeing in JOKER. The character has long been shrouded in mystery in comic book lore, and even those books that purport to reveal an origin – most prominently Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s controversial The Killing Joke – flip the script on us at the last moment. Despite Phillips’ initial protests, it’s a legacy that his film is indelibly tied to, awkwardly wedging in a subplot that gives Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen), his butler, and some kid named Bruce prominent cameos.

Moore’s comic was as much about the mirror figures of Batman and Joker as it was about the spiralling hellhole of humanity Moore perceived during the 80s. Yet Phillips and Silver focus on the latter. The stated key influences of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy, complete with Robert De Niro in the equivalent of the Jerry Lewis role, make the film more about angry male entitlement and obsession than justified outrage.

Which brings us to some of the more worrying turns of the film. The Joker has always been a problematic character when it comes mental health issues and misogyny, whether it is his homicidal tendencies or his abusive relationship with Harley Quinn. Here Fleck’s non-specific issues – which we are told led to previous institutionalisation and multiple meds – are how society labels him. “The thing about having a mental illness,” he scrawls in his barely literate journal, “is that people expect you to behave as if you don’t.”

Which would be a fine and dandy take if that treatment wasn’t coupled with such extreme violence. When Fleck lashes out, the faded 70s façade drips with gooey red. “It is not the intention of the film, the filmmakers or the studio to hold this character up as a hero,” said Warner Bros. in a statement. Yet at no point do we get any real disapproval of his actions either: yes, some of the people he kills are bad people, and Gotham is known for its vigilantism in later years. Violence is a liberating quality for the character: even though the film doesn’t actively condone his actions, it doesn’t condemn them either.

Neither does it fully pick a side politically, taking a kind of centre-right approach. It hates everyone in equal measure, which is textbook nihilism. The rich are sneering and dismissive of the rest of the world and deserve what they get in Fleck’s mind. Yet the film doesn’t support the grassroots protests of the masses either, depicting the popular uprising as unruly and a symptom of the societal disease. At least until a dramatic turn at the climax where it does appear to suggest that the Joker just might be onto something. At least The Dark Knight’s Joker was honest in wanting to watch the world burn, and the essential goodness of the people won out in Christopher Nolan’s Gotham.

Underneath these layers of grime and unpleasantness, there’s much to be admired on a technical level. Phoenix turns in a performance that easily matches his underrated outing in You Were Never Really Here, physically emaciated and concentrating a world of emotional pain into an upturned lip or a haunting teardrop. It’s a shame that the female characters, including the formidable Zazie Beetz (as a neighbour) and veteran Conroy, are nothing more than objects or barriers respectively. Lawrence Sher (Godzilla: King of the Monsters) nails the period look (whatever period that may be) in some gorgeous photography.

As the film approaches release, Phillips has begun to use the same comic books he derided to defend himself against accusations of toxic masculinity. “[I]t’s a fictional character in a fictional world that’s been around for 80 years,” he told the press, comparing his film to the comparatively positive reaction the violent John Wick films have received. This not only misses the point of the concerns but unseats the notion that this is a “real movie” acting in the real world.

Which brings us back to that other old joke about the brother of a man who thinks he’s a chicken. When asked why he doesn’t turn him in, he simply says he needed the eggs. While I’m paraphrasing that joke from the finale of another problematic 1970s filmmaker, the fact that a film like this exists in 2019 – post #MeToo and #TimesUp – is totally crazy, irrational, and absurd, but we keep going through it because someone still needs the eggs apparently. Even if they are scrambled.

2019 | US | DIRECTOR: Todd Phillips | WRITERS: Todd Phillips and Scott Silver | CAST: Joaquin Phoenix, Zazie Beetz, Frances Conroy, Robert De Niro | DISTRIBUTOR: Roasdshow Films (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 124 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 3 October 2019 (AUS)