Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

If you’re anything like me, then your journey into Middle-earth began with THE HOBBIT. In fact, talking with friends about this re-read, people have given me fond recollections of their childhood or affirmations that this was the book that started their love of reading.

Unlike a number of books covered in this column so far, this one was published in Tolkien’s lifetime. Indeed, it was the first of his Middle-earth books. It is also the most incongruous, being written for a younger audience and without as many references to the author’s deep Legendarium. Indeed, it wasn’t originally written with that larger tale in mind.

During the 1930s, Tolkien was in the middle of his academic career and his creative endeavours were limited to some writings for children – including the posthumously published Letters to Father Christmas and the original poem “The Adventures of Tom Bombadil” (1934) – and his invented Elvish languages. Tolkien recalled in a 1955 letter to W.H. Auden that he began writing it in 1930 on a whim. “On a blank leaf I scrawled: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ I did not and do not know why.“

“It had no necessary connexion with the mythology, but naturally became attracted towards this dominant construction in my mind, causing the tale to become larger and more heroic as it proceeded.“

– J.R.R. Tolkien in a letter to Christopher Bretherton, 16 July 1964

Now that we’re 82 years on from publication, THE HOBBIT has almost become a part of our collective unconscious. The titular fellow who lives in the aforementioned hole in the ground is Bilbo Baggins of Bag End. After a lengthy series of good mornings with the strange wizard Gandalf, he finds himself host to the 13 Dwarves who unceremoniously show up and help themselves to his pantry.

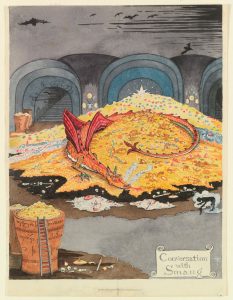

What follows is a child-friendly spin on Tolkien’s beloved Beowulf: a party of 13 hunting for a dragon (Smaug in this case, Grendel in the English epic poem); a thief stealing into a cave (Bilbo in this case); a literal skin changer in the form of Beorn (who can change into a bear); a magic ring; and numerous other northern European literary traditions with which Tolkien was intimately familiar. You get the strong sense reading this now that it was written for Tolkien and his family alone, disconnected as it is from Tolkien’s later works.

This playfulness of language and form is sharper when directly compared with the grander tales of The Silmarillion and, of course, its direct follow-up: a little something called The Lord of the Rings. Intended to be read by or to children, including Tolkien’s son and successor Christopher, this is a playful adventure that is structured as a series of mini-challenges around a larger quest. “For it is a children’s story,” notes Humphrey Carpenter in J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. “Despite the fact that it had been drawn into his mythology, Tolkien did not allow it to become overwhelmingly serious or even adult in tone, but it stuck to his original intention of amusing his own and other people’s children.”

When THE HOBBIT was published on 21 September 1937, it sold out all 1,500 copies rapidly. Yet over the years, the book has continued to evolve through the 1951, 1966, and 1978 editions. Some of these changes to the 1937 version seem weird and inconsequential. Bilbo’s pantry is stocked with “cold chicken and tomatoes” in the original text, but is changed to “cold chicken and pickles” in 1966. Yet others were to reconcile the text more closely with The Lord of the Rings.

The chapter “Riddles in the Dark,” which introduces Gollum, was famously rewritten to make Gollum more consistent with his later portrayal. In Appendix A of Douglas A. Anderson’s excellent The Annotated Hobbit (1988), he presents pages of text that were “entirely abandoned.” Featuring an apologetic and more pathetic version of Gollum, one who actually wants to give Bilbo the Ring, here’s an extract:

“Bilbo gathered that Gollum had a ring – a wonderful, beautiful ring…that he had been given for a birthday present, ages and ages before in old days when such rings were less common… “

It’s this beauty of enjoying it at a standalone novel that was arguably missed by Peter Jackson’s trilogy of films, elevating Tolkien’s lighthearted writing exercise into 9 hours of mythologising and action. The broader legends are certainly in the text – from the mentions of Gandalf’s fellow wizard Radagast to the looming threat of the Necromancer – and there’s a ridiculously large Battle of the Five armies that foreshadows The Lord of the Rings. Yet on a basic level these are all the things that any kid could imagine getting swept up in: whisked away from their comfortable home by a wizard and finding themselves in a golden cave with a dragon.

Despite the countless reprints, adaptations, games and merchandising, it has been argued that the greatest legacy of THE HOBBIT is The Lord of the Rings. After all, as a direct sequel it expands the mythology and uses the same basic narrative structure, albeit four times longer. Having now sold between 35 and 100 million copies, in addition to over 150 million copies of The Lord of the Rings, it’s one of the most read tales in modern history – and it all started in a hole in the ground.

In the next instalment of The Read Goes Ever On, I’ll start tackling the big one: The Lord of the Rings. Of course, it would be a fool’s errand to try and do it all in one column, so naturally The Fellowship of the Ring is the first one up to bat.