Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

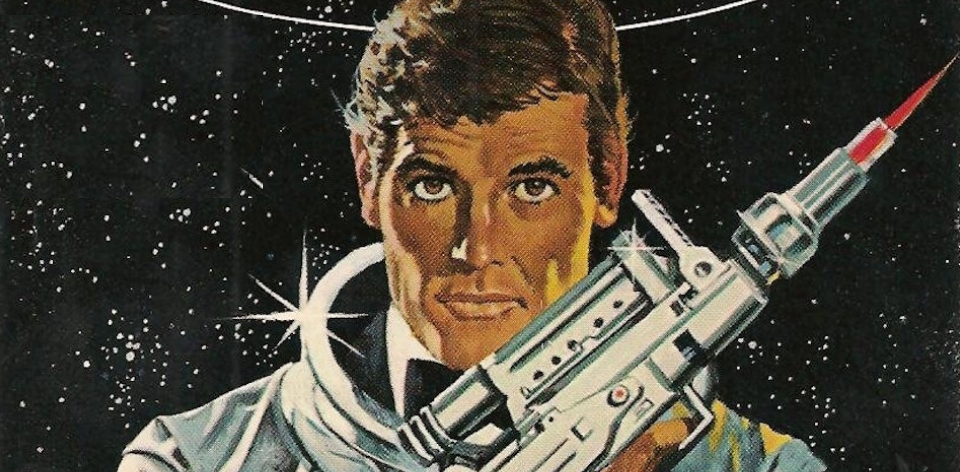

Here’s a strange little anomaly. A novelisation that’s not only better than the film that it’s based on, but an improvement over the original novel from which both derive their name.

When you break it down to its component parts, Christopher Wood’s screenplay to the film of Moonraker uses a similar plot device (of disappearing craft) to You Only Live Twice and his own screenplay for The Spy Who Loved Me. (All three were also directed by Lewis Gilbert). Throw in a weird romance between Jaws and a pigtailed girl, a Bond Girl named Holly Goodhead, and one of the cheesiest closing entendres to date (“I think he’s attempting re-entry”) and you have the least of the Bond films. Until Die Another Day, anyway.

Like Wood’s James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me, his screenplay was sufficiently different from Ian Fleming’s original novel that Eon Productions authorised an officially novelisation. Unlike The Spy Who Loved Me, this book is an almost direct adaptation of the screenplay with few additions and extra detail. Yet even while maintaining the qualities of one of the lesser films, Wood’s writing not only grounds the high-concept narrative but gives us a fresh perspective on its central characters.

Moonraker is not one of my favourite Flemings, featuring a semi-nihilistic Bond going up against a quintessential villain intent on domination and building a master race. Being one of Fleming’s earlier novels (published in 1955), the two decades that had passed meant that the space race had moved on significantly in that time. Despite The Spy Who Loved Me’s end-credits promise that “James Bond will return…in For Your Eyes Only,” the popularity of Star Wars prompted producers to bump Moonraker up in the production cycle.

So, it’s odd that Moonraker, both the film and the novel, spends much of its time on the ground, such as a lengthy sequence in Rio De Janeiro that includes a prominent use of Sugarloaf Mountain on both page and screen. In the latter, there’s a pervasive silliness that had followed the series at least since the latter days of Connery, replacing tangible threats with puns, Funniest Home Video sound effects, and sight gags than an entire Tim Conway comedy special.

Yet the novelisation is a slightly different beast, grounding 007 in ways that Eon Productions wasn’t willing to do at that stage. Yes, there’s still a character names Holly Goodhead and a metal chomping henchman – not to mention Felming’s penchant for casual homophobic and racial slurs – but there’s some knowing literary winks as well. Unshackled from his obsession with nipples in his previous novelisation, Wood spends a lot of time establishing an interiority to his minor characters, from a one-night stand “ashamed of her carnality” to the buffoonish character of Gray. (Never have I felt more seen and insulted at the same time).

Bond himself gets the same interior treatment, rounding out his character more than either Fleming or the film managed to do. In the original Moonraker novel, one of my primary complaints was that Bond doesn’t really do anything, failing to anticipate Drax’s plan and kind of giving up at the end. The suave Moore Bond doesn’t have this issue, commanding a fear that’s tangibly written (rather than just being nihilistic) and being launched into space amidst a laser battle.

Perhaps the perfect balance for this story is a mixture of all three of the sources, taking Fleming’s version of Bond, Wood’s penchant for writing large-scale action films, and a maybe a dash of that cheekiness. I must admit, while the puns were laid on a little too thick in the final film, I was a little disappointed to find that one of my favourite double entendres was absent from the novelisation. Caught out by his higher-ups canoodling in a capsule with Holly, Q’s unforgettable line (“I think he’s attempting re-entry, sir”) – delivered on-screen by the legendary Desmond Llewelyn – is sadly missing in action.

This would also represent the last Bond novelisation for another decade, when Bond continuation author John Gardner adapted Michael G. Wilson and Richard Maibaum’s Licence to Kill in 1989. In that time, the screen Bond would transition from Moore to Timothy Dalton and Gardner would begin a run of Fleming continuation novels that would ultimately outnumber the creator. So, if nothing else, JAMES BOND AND MOONRAKER is a totem at the crossroads of Eon Productions and Ian Fleming Publications. Beyond it, the world of Bond radically changed.

James Bond will return…in Licence Renewed.