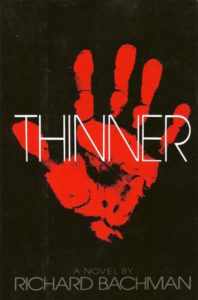

Welcome back to the feature column that explores Stephen King’s books in the order they were published! (Sort of!) The last Richard Bachman book before his ‘outing’ is a slice of body horror pie that gets slimmer as it goes. WARNING: in order to fully digest the book, this article bites into spoiler territory.

Weight is something I’ve struggled with for as long as I can remember. Even while sitting down to write this, five months of consistent and healthy weight loss are still unreasonably consumed by feelings of self-loathing for a body I desperately want to muscle into submission. It’s an anxiety that many share, and as the basis for a horror novel its both disturbing and uncomfortable.

The setup is simplicity itself. Billy Halleck is an overweight lawyer. I say this up front because he is established – by ticking chapter headings – as 246 pounds (about 111 kg) and 6 foot 2. Which is obese by the ol’ BMI scale. It’s important to remember this in objectivity because King has historically been a bit guilty of some casual fat-shaming, most notably in It (1986) and as recently as Mr. Mercedes (2014).

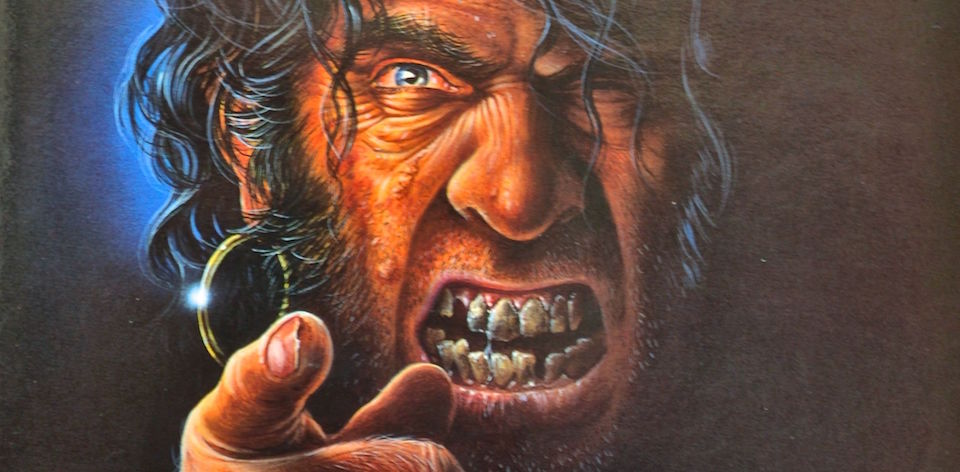

We meet this man shortly after getting off scot-free for the vehicular manslaughter of an elderly “Gypsy” woman, another dated term used liberally (along with ‘gyp’) in the text. Succumbing to uncontrollable weight loss, he soon finds himself alternatively distrusted by and horrifying to his nearest and dearest, especially as he insists that he is the victim of a “Gypsy curse” by a man known as Taduz Lemke.

Strangely, this is where THINNER works best, as a psychological horror tale of one man’s descent into motivated madness. We learn that those who encountered the ever-looming figure of Lemke, foreshadowed by constant descriptions of his cancerous nose, have each succumbed to physical ailments such as body scales and extreme acne. Billy’s constant denial of his own culpability in the death of Lemke’s daughter – it was his wife’s fault for giving him a hand job while driving, or the old woman’s for jaywalking – are classic setups begging for a comeuppance. “The definition of an asshole,” reflects one character later on, “is a guy who doesn’t believe what he’s seeing.”

“You were starting to sound a little like a Stephen King novel for a while there, but it’s not like that…”

When we last encountered Bachman (in 1982’s The Running Man) he was concerned with the lone man against the system. Indeed, all of King’s Bachman books have followed this theme to some extent: Rage’s visceral high school shooter, the relentless individualism of The Long Walk, and most definitely the grief swallowed up by the machine in Roadwork. This is the most King-ish of the Bachman releases to this point, the trademark Bachman unlikeable lead notwithstanding, and that’s possibly because it’s the most personal of the batch.

King once commented in an interview that when he was “236 pounds, and…smoked heavily,” he was ordered by his doctor to lose some weight. The perceived imposition saw King reflect on notions of the body, perceptions of self, how society views and judges the so-called overweight and underweight, and America’s obsession with food. There’s an uncomfortable truth that gets to the heart of the body horror aspects of the narrative. King has been playing with these ideas at least since his debut novel Carrie, in which the titular character’s menstruating body is told to contain itself (“Plug it up!”) before being unleashed in a telekinetic rage.

Reflecting on my own difficult relationship with my body, I recognised some of the passages King uses in my own self-defeating thinking. Likewise, the obsession with weighing, the way “people would stare at you” and all the self-talk that comes with it. One becomes convinced that every look is a judgment, when the harsh reality is that most people are thinking about their own damn selves and you’re just something that passed in front of their eyeballs. Of course, I recognise that none of this is rational.

“Billy Halleck discovered a crude sort of ritual had attached itself to his procedure for weighing himself…”

Yet despite this resonating with me on some level, or at least ‘getting’ some of King’s thinking, THINNER is a book that aptly loses substance as it goes. The character-based first act gives way to a slower second half. Attempting to combine Billy’s pursuits with some of the supernatural elements of (imagined?) Gypsy culture, it feels like King wrote himself into a corner, much as he did with Christine. Case in point is the late introduction of mobster Richie “The Hammer” Ginelli, who bizarrely takes over the narrative with a side story of how he tried to muscle the Gypsy camp.

The finale comes full circle, relying on a carefully constructed privilege to lead Billy to the Twilight Zone conclusion. Lemke gives our thin man a simple choice. Actually he gives him a pie. Billy starts to gain wait again, but he’s threatened that his curse will return if someone doesn’t eat the dessert within the next few weeks. He doesn’t eat it himself, of course, still refusing to take responsibility for his own actions. Leaving it for his wife, it’s also consumed by his daughter. Oh the irony! The pie-rony!

The heavy-handed ‘humble pie’ conclusion (or ‘just desserts’ if you will) makes this feel more like a winking short story than a novel. Pile on a liberal dose of cultural stereotyping, and you have something that doesn’t quite weigh up 36 years later. Yet there’s moments of genius in here, representative of the brief window between Bachman’s anonymity and the sales spikes from his outing. In fact, Misery was originally planned as a Bachman book before the reveal. Sadly, Bachman died in late 1985 of “cancer of the pseudonym, a rare form of schizonomia.”

Bachman will return…in 1996’s The Regulators! Until then: it’s all King, all the time! From THINNER to Skeleton Crew, the next instalment of Inconstant Reader rolls on in chronological order for a change. While you’re here, go check out Batrock.net, where my buddy Alex Doenau is running through this Stephen King adventure with me.