Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Returning to The Lord of the Rings in 2020, almost three decades after I first read the mammoth tome, is a very different experience. Apart from multiple reads and reinterpretations in that time, the story is now unavoidably filtered through Peter Jackson’s films.

At the time those films came out, I felt that they were a fairly accurate translation of the books. Yet as good as they are, in the course of reading more of Tolkien’s legendarium over the last year – from The Silmarillion through to Unfinished Tales – I’ve come to appreciate them as something more. After all, this is the first time I’ve attempted a re-read within the context of it being (in Tolkien’s words) “one long Saga of the Jewels and the Rings.”

What we now know as THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING is actually the first two parts of a six ‘book’ saga that Tolkien always saw as the singular The Lord of the Rings. So, perhaps what surprised me most on this re-read was remembering just how much of this book is front-loaded with matters “concerning Hobbits.” Beginning with a recap of the events of The Hobbit for the uninitiated, as well as a few references to the First and Second Ages, this really does start as a sequel to The Hobbit.

“Among the Wise I am the only one that goes in for hobbit-lore: an obscure branch of knowledge, but full of surprises.”

Despite referring to The Hobbit “sequel” in letters throughout 1937, Tolkien didn’t always see the book as serving this function. “Not ever intending any sequel,” he wrote to C. A. Furth at Allen & Unwin in 1938, “I fear I squandered all my favourite ‘motifs’ and characters on the original ‘Hobbit‘.” By the following year, Furth is the recipient of a letter where the first mention of the title is made: “I think The Lord of the Rings is in itself a good deal better than The Hobbit, but it may not prove a very fit sequel.”

For the first book (‘The Ring Sets Out’), or roughly half of THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING, this is for all intents and purposes a Hobbit sequel. Repeating the basic format of its predecessor, Frodo Baggins is whisked away on an unexpected journey that initially has no particular urgency. We’re immersed in Hobbiton for a much longer period than I remembered, and there’s a fairly leisurely gap between the opening party and Frodo’s ultimate departure from the Shire. In retrospect, this serves as Tolkien’s bridge between his ‘children’s’ tale and the darker direction of his growing legend.

In his 1954 review of the book for The New York Times, no less a figure than W.H. Auden spoke of this shift in tone between the two parts of the book. “I think some readers may find the opening chapter a little shy-making, but they must not let themselves be put off, for, once the story gets moving, this initial archness disappears.” He adds that “Mr. Tolkien’s invention is unflagging, and, on the primitive level of wanting to know what happens next…[the book] is at least as good as The Thirty-Nine Steps.”

With his heroes pursued by the Nazgûl, Tolkien’s pace drives the hobbits into the Old Forest, where his oft returned to figure of Tom Bombadil opens up the mythology to new readers. It’s often like walking through the relic of a forgotten age which, for Tolkien at least, is exactly what we are doing. If you are like me, some of your re-reads may have tended towards ‘skimming’ through the lengthier songs and poems. Reading them now, they act as windows to the past. References are made to Elbereth (“Queen of the Stars”), for example, and Morgoth’s greatest winged dragon, Ancalagon. Meanwhile, Aragorn sings a lengthy song of Beren and Lúthien, the tragic elf-human romance that is one of the Great Tales of the First Age.

“The Elder Days are gone. The Middle Days are passing. The Younger Days are beginning. The time of the Elves is over, but our time is at hand…”

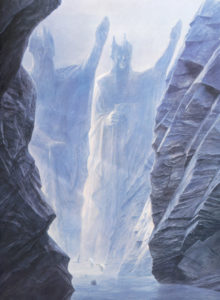

These fragments become the primary text by Book II (‘The Ring Goes South’), where there’s far more recognisable moments filled with forward momentum. The familiar ‘The Council of Elrond’ has a long monologue from the chapter’s titular character as he takes deep dives into Tolkien’s own mythology: it’s infinitely fascinating in context, even if it does feel like pages of exposition all at once. Of course, by the time the Fellowship sails through the Argonath, the giant Númenorean sentinels (also known as the Pillars of the Kings) and relics of the Second Age, the Fellowship is quite literally passing through the monuments to that hitherto unseen past.

Structurally, Book II is also where all the story’s biggest moments live, or all the great ‘set-pieces’ to put it in cinematic terms. As the ‘fellowship’ trudge across Caradhras in the Misty Mountains, you can feel the cold of the cliff-face. There’s Gandalf’s confrontation with Balrog, another remnant of Morgoth’s time, and really the whole Moria sequence is gripping stuff. Boromir’s confrontation with Frodo is a strong character moment amidst all the sweeping world-building. This is a lived-in universe, after all, and we are just passing through.

It would take an article several thousand words longer to really get into all the connections and details that I picked up on this time, from Radagast and Saruman to the countless mentions of the Númenóreans. I fully recognise that these are nothing new to existing devotees and Wiki owners, but with the added knowledge that comes with the broader context of the Legendarium, I really felt like I was reading an entirely new book for the first time. Or as Bilbo puts it: “There are whole chapters of stuff before you ever got here.”

“This is how it would begin. But it would not stop with that, alas!”

We modern readers have the advantage of almost seven decades of Tolkien scholarship and fandom to draw on when speaking of these books, couched in the genre we now casually call ‘high fantasy.’ Contemporary critics had to judge it on a different set of merits, but recognised it’s impact as a genre starter. Naomi Mitchison, writing for The New Statesman (‘One Ring to Bind Them’), called it “extraordinary, terrifying and beautiful” and prophetically added “It is timeless and will go on”. Not all were as kind: writer/critic Edmund Wilson in ‘Oo, Those Awful Orcs’ for Nation called it a “children’s book which has somehow got out of hand.” Perhaps Tolkien’s friend and colleague C.S. Lewis sums it up best in his 1954 review (‘The gods return to earth’): “This book is like lightning from a clear sky…it makes not a return but an advance or revolution: the conquest of new territory.”

My journey through the First Age (and bits of the Second) has not always been an easy one, and nor is it completely over. The Silmarillion‘s reputation is hard won, and The Children of Húrin and The Fall of Gondolin are some serious deep dish servings. Yet now that I’m back up to the Third Age, I get a simple joy just from encountering the enigmatic Tom Bombadil, knowing the figure the Elves called Iarwain Ben-adar has watched the steady march of the First Age through to the Fourth. It’s something to think about while I ponder what Bill the Pony is up to right now.

In the next instalment of The Read Goes Ever On, we follow the ring East! It will probably come as no surprise that I’ll be hitting up Books III and IV of The Lord of the Rings next: better known as The Two Towers.