Starting my journey through a century of Japanese cinema, this seminal film paved the way for countless chanbara films.

So, earlier this year the BFI published a list of the best Japanese film from each year until now. It comes with a massive amount of caveats, like any list should. (After all, 1954 saw the release of Godzilla, Seven Samurai, Sansho Dayu, Late Chrysanthemums to name but a few). Yet they provide a good jumping off point for exploration, either to fill in some gaps or wander down hitherto unclimbed branches.

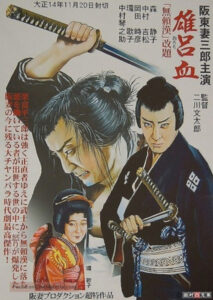

So was the case with Buntarō Futagawa’s OROCHI (雄呂血), a film I was vaguely aware of from reading other lists and books on Japanese film, but had never really dipped into the early silent era much. To be honest, I’d never really gone back much further than Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Water Magician, which I was lucky enough to see on the big screen at an art gallery a few years back.

Like other movies of the era, it is not a ‘silent film’ in the way that we traditionally use that term in the west. Of course, no silent film ever really lived up to that name: they were always accompanied by music and occasionally live sound effects. In Japan it was the live benshi performance that provided the audio: a theatrical performer that provided commentary, voices and description. Originally used for foreign films, the benshi became an integral part of Japan’s silent era, one that continued well into the 1930s.

Which makes OROCHI far more engaging for modern sensibilities than many other films of the period. The narrative, written by Rokuhei Susukita, is an otherwise conventional morality tale, one in which samurai Heizaburo Kuritomi (Tsumasaburo “Bantsuma” Bando) has fallen on hard times and is falsely accused of a crime.

Futagawa’s accomplishments are even more remarkable in the face of his constraints. Firstly, there’s the technical ones of filmmaking in the 1920s. If you look beyond the sped-up aesthetic of period films, you’ll see some of the marks of modern chanbara films that persist to this day. The detailed costuming and elegant sword fights are in contrast with the kabuki-style clashes commonly seen at the time. Just look at this final sword fight for example:

The more significant constraints remain literally invisible, with cuts and edits resulting from the increasingly conservative environment in the transition period between the Taisho and Showa eras. Over 20% of the film was reportedly cut due to censorship, and the name of the film was changed from Outlaw to OROCHI (meaning serpent) to avoid being overtly seditious.

Yet Futagawa and Susukita’s film leaves us with the unmistakable message of injustice permeating Japanese society. “There is no justice in this world,” says the closing narration, contrasting Heizaburo’s fate with that of the corrupt but respected lord Jirozo. “Not all who wear the name of villain, are evil men. Not all who are respected as noble men are worthy of the name. In our world live many whose false masks hide the vice and wickedness of their souls.” Almost a century later, that entire speech could be a meme.

OROCHI is still available to us quite freely on home formats and various popular streaming video sites if you care to go looking. It’s a good thing too: while it isn’t the start of the Japanese cinema story, it’s a great place to start your chronological journey. Indeed, I may skip around a bit after this and not go straight into Teinosuke Kinugasa’s A Page of Madness. I’ve got my eye on the 1970s next…

Read more coverage of Japanese films from the silent era to today. Plus go beyond Japan with more film from Asia in Focus.