What do crustaceans, bats, hibachi grills and bicycles have in common? Not much, and that’s kind of the point.

‘Experimental cinema’ is becoming less of a specialised term, as so many icons of avant-garde film are getting wider exposure thanks to the ubiquity of web and mobile content delivery.

In the context of a country that has produced the likes of Iimura Takahiko, Shūji Terayama, Nobuhiko Obayashi and Sion Sono, those fringes can rapidly become the status quo at festivals. Indeed, less than I decade ago I thought Shunichiro Miki’s The Warped Forest was the weirdest Japanese film I’d ever see. To paraphrase Roy Batty, if you could only see what I’ve seen with these eyes since then.

Which brings us to the experimental spotlight at JAPAN CUTS this year, a mixture of features and shorts that, according to the festival program,”push the limits of film form and defy categorization in their exploration of unconventional and evocative storytelling.”

Isamu Hirabayashi’s SHELL AND JOINT is the finest insect and crustacean-based film you’ll see this year. Semi-structured around Nitobe and Sakamoto, childhood friends who work at the front desk of a capsule hotel, a variety of figures drift in and out over the course of a loose 154 minutes. I have to admit that my mind started wandering around the 90 minute mark and never fully returned from its voyage. Then again, you don’t spend your entire gallery visit on one piece of art, do you?

Then there’s KINTA AND GINJI (金太と銀次), which serves as a nice companion piece. If it wasn’t for the avant-garde leanings, it would be your typical friendship between an anthropomorphic tanuki (racoon dog) and a robot. You know, for kids? Like Hirabayashi’s film, co-writers and directors Takuya Dairiki and Takashi Miura use long takes, microscopic imagery and offbeat music as a vehicle for long discussions on the nature of being. It’s the kind of film that you can just let wash over you and find it delightfully charming in the process.

“You idiot. All novels and movies are truth-based.”

Slipping on CENOTE (TS’ONOT) late one night, I found myself drifting in and out of awareness in this floating world. While the back half didn’t work for me as much as the first, Kaori Oda’s exploration of sources of water that in ancient Mayan civilization I can totally see this playing on a loop inside a giant 360-degree cinema where life is but a dream and boats are merrily rowed.

As with previous years, JAPAN CUTS has given us access to a selection of experimental short films as well. This year they play with animation, the documentary form and soundscapes to present a variety of ideas.

Mizuki Kiyama’s BATH HOUSE OF WHALES, for example, uses a paint on glass animation technique for wonderfully evocative vignette crafted with a sense of wonder, as if viewed through the eyes of a child.

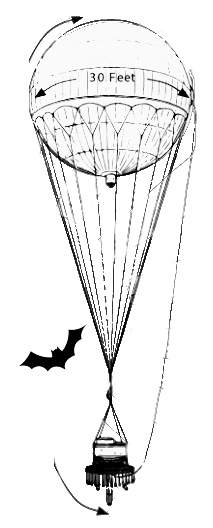

Similarly, Kota Takeuchi’s BLIND BOMBING, FILMED BY A BAT is ostensibly a documentary about Japanese balloon bombing, it’s mixed in with constant bat sounds as its told through the perspective of the titular chiroptera. It’s an approach that doesn’t quite gel with the subject matter if you’re here to learn, but it also mirrors the actions of a balloon by floating around for a bit.

Other shorts use the medium to simply observe. Araki Yu’s FUEL, which focuses on an expert griller working at one of the oldest Robata-yaki restaurants in Japan, is like slow TV. It’s often so still that I thought my stream had stopped entirely, but always remains engaging and meditative.

WHEEL MUSIC, from Nao Yoshigai, lets the viewer float along with a bike as it spins past construction for the (now delayed) Tokyo Olympics. It’s interesting that this approach is considered experimental while it’s been the stock-in-trade for documentarians like Kazuhira Soda. Either way, both of these shorts could be put on a loop for hours and you’d be in a much calmer space.

Which brings us back to the question ‘what is experimental film?’ If it’s any film that pushes the expectations of the format, then each of these films strive for that in different ways. In a year where we lost the great Obayashi, it’s nice to know that his spirit is alive in some form.

Read more coverage of Japanese films from the silent era to festivals and other contemporary releases. Plus go beyond Japan with more film from Asia in Focus.