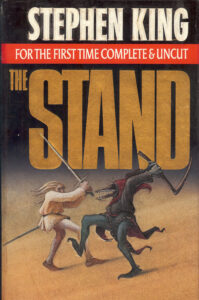

Welcome back to the feature column that explores Stephen King’s books in the order they were published…sort of! Remastered and expanded in the same year as Four Past Midnight, King’s re-release of his pandemic parable is more epic than ever.

WARNING: this article does not stand in the way of spoilers.

The first time I read THE STAND I got sick. So much so that I had to take two weeks off work with a respiratory illness that just wouldn’t go away. The irony was not lost on me. Little did I know that only three years later, I would be reading it again while the world was in the grip of an actual pandemic.

When the Coronavirus hit in late 2019, people began to compare the rapidly spreading outbreak to King’s book. “I wrote THE STAND about a pandemic that wipes out most of the human race,” he told The Guardian in March this year, “and thank God this one isn’t that bad, but I wrote that in 1979 and ever since then this has just been waiting to happen. The fact that nobody really seemed prepared still mystifies me.”

Part of that has to do with the way that this, and The Walking Dead in its various mediums, have popularised the end times in the cultural consciousness. We imagine a handful of survivors battling their way through a decaying world. What we didn’t foresee was a battle over toilet paper, people protesting the right not to wear a mask, and lots of sitting around. So much sitting around.

“Someone had finally invented a chain letter that really worked. A very lethal chain letter.”

Originally published in 1978, and again in 1990 as the Complete and Uncut Edition (which is the only version I’ve read), King calls this his “long tale of dark Christianity.” Which is as good as a description as any I’ve seen. More specifically, it concerns the survivors of a plague accidentally unleashed by the military, borne of a superflu known variously as Captain Tripps or “tube neck.” In the aftermath, survivors are inexplicably drawn to two figures: the benign 108-year-old Mother Abigail in Colorado, and Randall Flagg (aka the Dark Man, the Tall Man, or the Walkin’ Dude) in Las Vegas.

King played with the idea of the Captain Trip(p)s superflu as early as a 1969 short story called “Night Surf” (later published in Night Shift). In Danse Macabre, he speaks about it being a combination of hearing the phrase “Once in every generation the plague will fall among them” on religious radio and seeing Patty Hearst’s face and writing down “A dark man with no face.” This serendipitous origin is still evident in a book that takes its own damn time, and is arguably King at his most indulgent (in all the right ways). He’s frequently referred to it as his Lord of the Rings.

There’s so much to like in this book, especially when the narrative resonates with current world events. His descriptions of how the flu spreads is bang on, right down to a government playing it down as a “moderately serious outbreak of influenza” – right before the President contracts it! (There’s even the phrase “I think the cure was a lot worse than the disease.”) The relationships that King creates between characters are heartrending, and I challenge anybody who makes it to Tom Cullen on Christmas Day to not start tearing up.

What I had forgotten about the book was just how icky it gets at times. I’m not talking about the legitimate terror of certain sequences – the journey through the tunnel still grips me with fear – but rather those less pleasant aspects of human nature that King occasional revels in.

It’s an oddly libidinous tome at times. I’d forgotten about the multiple times rape is used as a plot device: at least once with a gun, and later one where the victim derives pleasure apparently. The latter is especially gratuitous, as it’s ostensibly Flagg attempting to spread his demon seed, a plot line that goes nowhere. Indeed, there’s entire strands that King doesn’t quite know what to do with, such as the character of Joe/Leo who effectively disappears after being a different kind of creepy child.

When I last read THE STAND, I was doing so within the context of an ambitious intertextual reading of The Dark Tower saga. I’ve since completed that reading, and read a few dozen more King books since then. So there were countless references that I picked up. Mother Abigail’s “shine” was always evident, and Roland’s ka-tet visits a superflu ravaged Topeka in Wizard and Glass. Of course, Randall Flagg himself is the very same Man in Black from The Dark Tower, but he’s more directly in Eyes of the Dragon. In this uncut edition, the epilogue concludes with what is now an obvious reference to ka.

“Life was such a wheel that no man could stand upon it for long. And it always, at the end, came round to the same place again.”

“There is no moral to THE STAND,” wrote King in his memoir On Writing, “but if the theme stands out clearly enough, those discussing it may offer their own morals and conclusions.” Which bring us back to 2020, where life imitates art, right down to a potentially world-changing clash in next week’s US Election. It’s probably no fluke that a second TV adaptation is due out in December.

Over 40 years after its first publication, and 30 since this edition, King’s flawed masterpiece is a book that keeps finding the right audience at the right time. Or as King once wrote, “THE STAND is mostly a hopeful book that echoes Albert Camus’s remark that ‘happiness, too, is inevitable.'”

Next time, Inconstant Reader gets tied down with 1992’s Gerald’s Game. (We already covered The Dark Tower and Needful Things elsewhere). While you’re here, go check out Batrock.net, where my buddy Alex Doenau is running through this Stephen King adventure with me.