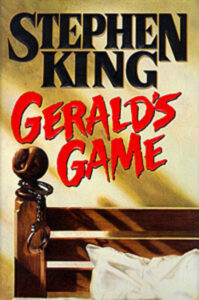

Welcome back to the feature column that explores Stephen King’s books in the order they were published…sort of! A novel that cuffs you to the bed, gets inside your head and then goes to some unexpected places.

WARNING: this wouldn’t be a true game without spoilers.

When I first read GERALD’S GAME upon its release in 1992, I was an innocent 13-year-old. I’d felt a giddy thrill at cracking open what seemed to be a dark, slightly naughty, and surprisingly scary book. While I can never be entirely sure that I finished it then, a return to this book 28 years later comes with its own modicum of darkness.

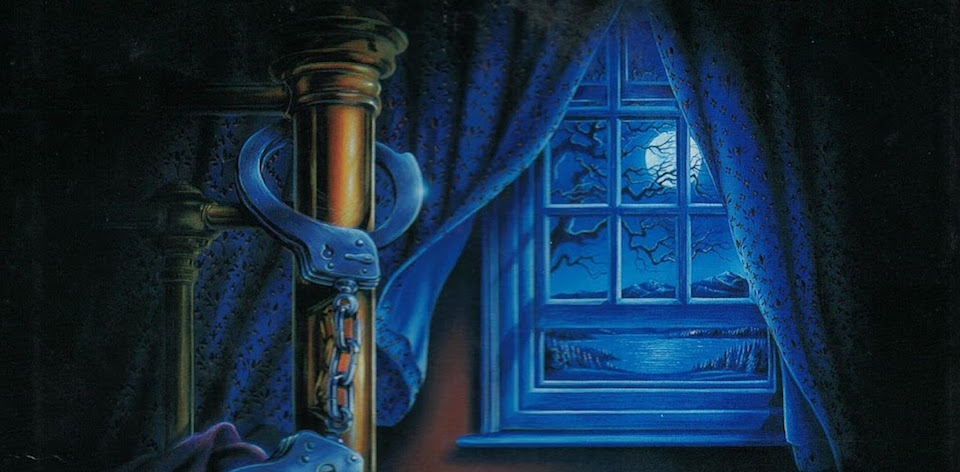

King wastes very little time in getting down to business. We meet Jessie and her husband Gerald in a remote cabin. Handcuffed to the bed, Jessie has grown tired of Gerald’s penchant for a bit of light bondage and asks him to stop. When he refuses to listen, she responds with a more forceful kick. Gerald’s resulting heart attack and death leaves her stranded on the bed, alone but for an increasing number of voices in her head, a stray hungry dog and…something or someone else she can’t quite identify.

One of the things that King has always done well is explore the inner world of his characters. Even when writing about the vilest humans, he manages to crawl inside their minds and see out through their eyes for a while. Yet rarely has he tapped into a character’s interiority as rapidly and so completely as he does with this novel. It’s a bit like one of Roman Polanski’s films: think Repulsion or The Tenant.

“This was going from bad to worse to horrible, and the scariest part was how fast it was happening.”

As Jessie lays prone on the bed, a chorus of voices offer helpful (and sometimes less than helpful) advice. They take on various personas, from ‘Goody Burlingame,’ an idealised version of a ‘good wife’ through to Ruth, a forthright representation of her colleague roommate. What gradually emerges are the emotional scars of a childhood molestation Jessie has never fully confronted. In this sense, it’s King’s most nuanced exploration of human strength and fears, viewed entirely through the singular lens of one person’s mind.

Which is where this book is at its strongest: exploring those inner fears and their possible manifestations in the real world. The often overused motif of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven is referenced throughout. Is that a stranger rapping at her chamber door? Is there something even worse that her recently ex-husband being gnawed on by a dog. Is it “only made of moonlight” and nothing more? The source of much of the book’s tension is in not knowing, although King deflates some of this in the later chapters.

Indeed, there’s something starkly modern (and unfortunately timeless) about King’s underlying themes of abuse and recovery. From the outset, Jessie speaks directly to what would now be called a #MeToo moment. “It isn’t that he can’t read you,” she tells herself, “it’s just that sometimes, toots, he doesn’t want to.” Realising that her husband intends to rape her, she resolves to “Just let him do it and it will be done.” It becomes a trigger for memories of her father’s abuse, something else she’s rationalised in various ways over the years.

What did surprise me was how much King managed to get under my skin while literally getting under Jessie’s epidermis. It’s been a long-standing personal joke with a friend that King’s books are unputdownable from the 70% mark, and like clockwork King turns it up several notches at this juncture.

Unfortunately, the denouement takes the book in a strange direction. Jessie liberates herself and hops into a car, but spots the figure she dubbed the ‘Space Cowboy’ (for the Steve Miller song) in the backseat. She passes out, and when she comes to, we’re treated to the first person narrative of her recovery, a new relationship and a reveal. The ‘Space Cowboy’ was in fact a necrophile who had been prowling local cabins.

“New England Gothic, by way of The Journal of Aberrant Psychiatry.”

Never have I squirmed so much as I did when reading about Jessie degloving her own hand to escape her shackles, and the moments after her liberation left me as woozy and heart-poundy as our blood-deficient heroine. Perhaps the last time I felt that viscerally affected was by another Poe story, Murders of the Rue Morgue, during a description of fragments of a scalp that were removed by an orangutan.

This latter bit didn’t sit quite right with me. Despite some nice references to Castle County’s Sheriff Norris Ridgewick (last seen in Needful Things) – and police evidence labelled “217” in a wink to The Shining – it felt like too much of an over-explanation to be truly satisfying. The story was over for me at the point of Jessie’s freedom, but King should be credited with at least acknowledging the importance of recovery as a process.

GERALD’S GAME got a second life in 2017 when it was adapted by Mike Flanagan for Netflix. The director went onto helm Doctor Sleep (based on the novel of the same name), bringing direct references to “the beam” of the The Dark Tower into both films. King has his own connections here, laying Jessie in the path of an eclipse and giving her visions of a woman kneeling in blackberry tangles – one who will turn up in another book later that year.

Hold onto that last thought, Inconstant Readers! Next time, Inconstant Reader hits up Dolores Claiborne. While you’re here, go check out Batrock.net, where my buddy Alex Doenau is running through this Stephen King adventure with me.