Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases a very slow re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Mourning a book is a real thing. Some talk about the idea of a ‘book hangover,’ the “feeling when a reader finishes a book—usually fiction—and they can’t stop thinking about the fictional world that has run out of pages.” So, how do you say goodbye to one of the most epic and all-encompassing sagas of modern literature?

BILBO’S LAST SONG is Tolkien’s lament for the world that was and, on a literal level, the passing of Bilbo from Middle-earth to the Undying Lands in the west. The brief piece — comprising of three stanzas, made up of four rhyming couplets apiece — is sung by Bilbo right before he is about to board the ship to Valinor.

While it is likely it was written sometime in the 1940s or early 1950s, when the coda to LOTR had formed in Tolkien’s mind, the origin of the publication of BILBO’S LAST SONG is also tied to the passing of a legacy in some ways. In 1968, when Tolkien was aged 76, he retired from Oxford and moved to Bournemouth. After a severe leg injury, involving surgery and a cast, he found unpacking his 48 crates of books a bit of a chore. His publisher Allen & Unwin sent secretary Margaret Joy Hill to help him, and she discovered the poem in the pages of an old exercise book. In October 1971, Tolkien formally gifted the poem to her, which she arranged to be published shortly after his death in 1973.

It begins with an ending. “Day is ended, dim my eyes, but journey long before me lies. Farewell, friends! I hear the call. The ship’s beside the stony wall.” The meaning of the first three lines is clear, especially within the context of LOTR’s denouement. The ship beside the stony wall was one crafted by Círdan the Shipwright, who saved a large ship to ferry Elrond, Gandalf, Galadriel, Bilbo and Frodo to Valinor. You may recall from The Silmarillion that mortals were forbidden to travel there following the destruction of the island of Númenor. As ring bearers, Bilbo and Frodo were given permission to enter — with a little advocacy from Gandalf and Arwen, the latter of whom took the “choice of Lúthien” and remained on Middle-earth.

“Shadows long before me lie, beneath the ever-bending sky,” muses Bilbo in the second stanza, acknowledging not just his own imminent passing but its place in the broader cycle. “But islands lie behind the Sun that I shall raise ere all is done; lands there are to west of West, where night is quiet and sleep is rest.” The lands to the West are, of course, Valinor, previously inaccessible to all but the Eldar. It’s the first direct reference to Bilbo’s destination, and his passing from one world into the next.

Bilbo then says that his journey is “Guided by the Lonely Star,” which in this case refers to Star of Eärendil, or the Evening Star. The star is actually a Silmaril, carried into the sky by Eärendil the Mariner, who wore the star on his brow to guide him. It is the brightest star in the sky, containing the light of the Two Trees that were ultimately used to make the Sun and Moon by the Valar. In the Second Age, the star guided Edain to Númenor. Sam and Frodo also used the light from the Elves “most beloved star” to pierce through the darkness at various stages of their journey (including Shelob’s lair). It’s a beautiful bit of symmetry, in which the end of the Third Age is marked by the Evening Star returning to its role of maritime guide.

In the final stanza, Bilbo concludes: “I seek the West, and fields and mountains ever blest. Farewell to Middle-earth at last. I see the Star above my mast!” Bilbo is 131 years old by the time he departs, surpassing Old Took as the oldest hobbit who ever lived. Yet the farewell to Middle-earth is also a farewell to the Third Age, and as the Elves and ring bearers leave the Elvish port city of the Grey Havens, the Age of Men begins. As such, this poem could have very easily fit into the final pages of The Return of the King, but was omitted in favour of other conclusions.

When Peter Jackson made his film of The Return of the King, he was unable to use BILBO’S LAST SONG but instead commissioned Into the West, a similar song written by Fran Walsh, Annie Lennox and Howard Shore, performed by Lennox during the credits. You can hear BILBO’S LAST SONG performed in several places, the most notable of which is Donald Swann’s composition embedded above. (Swann would also include it subsequent editions of The Road Goes Ever On, a collection of Tolkien’s poetry set to music). There’s Stephen Oliver’s version for the BBC radio adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, and a quick search will reveal several live performances floating around.

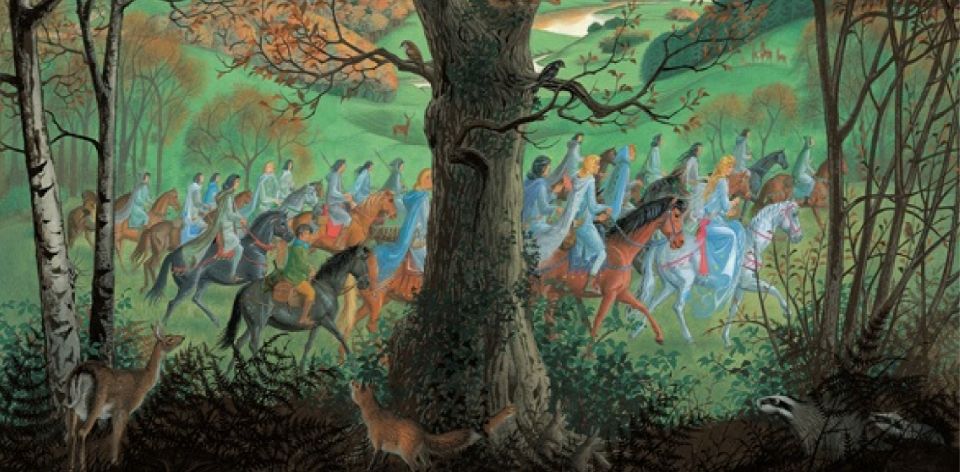

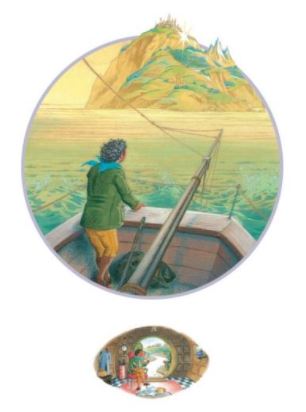

While it was popularised as a poster in 1974, this later storybook edition also contains some beautiful illustrations from Pauline Baynes, with each double-page spread dedicated to a separate rhyming couplet framed in ornate leaves. In the spirit of looking back, the recto pages contain roundels depicting Bilbo’s adventures from The Hobbit and key sequences from The Lord of the Rings. The net effect is feeling as though we’ve stumbled across one of the works that Bilbo himself may have created along the way.

A beautiful read for those not quite ready to plunge into the appendices, but not yet ready to bid farewell to their recent (re)read of The Lord of the Rings. As evidenced by this excessively long piece, it might only be 149 words long but it contains a weight that transcends its deceptively diminutive package. Kind of like the hobbit that penned it.

In the next chapter of The Read Goes Ever On, I’ll finally dive into those LOTR Appendices. For now, I’ll drift off into the Undying Lands on this big ship made of candy and a neverending reading list.