Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases a very slow re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

“I now wish that no appendices had been promised!” declared Tolkien in a March 1955 letter to publisher Rayner Unwin. For I think their appearance in truncated and compressed form will satisfy nobody: certainly not me; clearly from the (appalling mass of) letters I receive not those people who like that kind of thing – astonishingly many; while those who enjoy the book as an ‘heroic romance’ only, and find ‘unexplained vistas’ part of the literary effect, will neglect the appendices, very properly.”

If you’re anything like me, you probably gave the Appendices a quick speed read at the end of The Lord of the Rings. After all, with an ending like that, it’s hard to find the mental space to switch into study mode. Yet my purpose in this journey through Tolkien was to learn more about the background and construction of his fictional worlds and languages.

This has become especially pertinent as we approach Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings streaming series, purportedly set in the Second Age, the period following the climactic banishment of Morgoth into the Void by the Lords of the West (as described in The Silmarillion) and the first defeat of Sauron at the hands of the Last Alliance of Elves and Men.

So, what’s in the Appendices? Split into six sections — labelled Appendix A through F — it sets out to provide a potted history of cultures, genealogies, and languages for the saga. As we well know, The Lord of the Rings was but a slim fraction of a great saga of jewels and rings. When writing about The Fellowship of the Ring, I noted that it’s “like walking through the relic of a forgotten age which, for Tolkien at least, is exactly what we are doing.” So by this measure, the Appendices are something of a guidebook to those relics, still within the framing device of the fictional Red Book of Westmarch that Tolkien is ‘inspired’ by.

Appendix A (or the Annals of the Kings and Rulers) is perhaps the most detailed background in the set. Before The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales or the extensive work of Christopher Tolkien, it was the most extensive information avid readers had about the First and Second Ages. “It’s principle purpose is to illustrate the War of the Ring and its origins, and to fill up some of the gaps in the main story.” From tales of the Valar to the fall of Númenor, and from the Battle of the Fives Armies to the final fall of Sauron, Tolkien does just that. It mainly examines the The Númenórean Kings, along with stories of the Men of Gondor and Rohan.

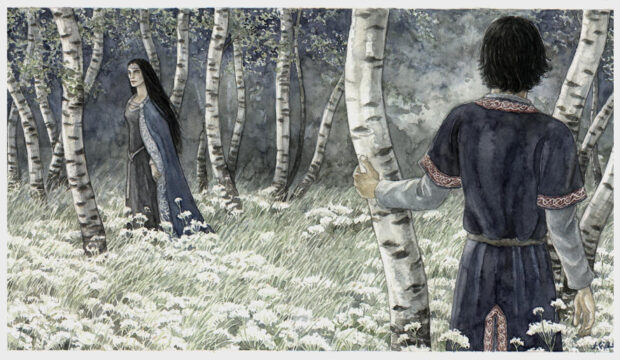

Yet there are some grand stories that stand on their own in this section, the most notable being of Aragorn and Arwen. If you recall in The Return of the King, the couple wed, with Arwen making the “choice of Lúthien” to become mortal. Here we get the tale of their first meeting and the events leading up to that choice, making it a vital piece in the puzzle. In a draft letter to Michael Straight of the New Republic, Tolkien stated as much: “I regard the tale of Arwen and Aragorn as the most important of the Appendices; it is pan of the essential story, and is only placed so, because it could not be worked into the main narrative without destroying its structure.” It partly explains why the union sometimes feels like an afterthought in the main text. Drawing parallels with the epic First Age tale of Beren and Lúthien, it provided filmmaker Peter Jackson ample fodder for a romantic thread throughout his first cinematic trilogy.

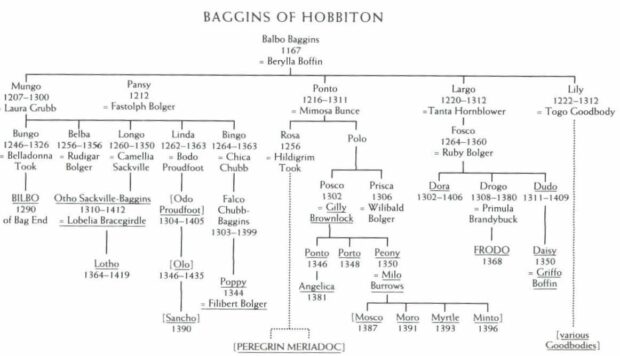

The remaining Appendices act more in the vein of reference material for the Tolkien scholar and my geeky brethren alike. Appendix B (The Tale of Years) is a list of dates from the Second, Third, and even Fourth Ages, the latter of which is especially sweet for those who want to know the final fates of Aragorn, Legolas, Sam and Gimli to name a few. Appendix C (Family Trees) contains the family trees of Frodo, Pippin, Merry and Sam, the latter of whom leaves the Red Book to his daughter before going to the Havens as the last Ringbearer. Appendix D (Calendars) reconciles the Shire calendar with the world of Elves and Men. Finally, Appendix E (Writing and Spelling) and F explain pronunciation and forms of writing and the difficulty in ‘translating’ the Red Book’s languages. For those who are interested in Tolkien as a language scholar, these are clearly vital texts.

In a letter to Allen & Unwin in January 1961, Tolkien acknowledged the realities of publishing costs, but argued that they would increase sales. “Actually, an analysis of many hundreds of letters shows that the Appendices have played a very large part in reader’s pleasure, in turning library readers into purchasers (since the Appendices are needed for reference), and in creating the demand for another book. A sharp distinction must be drawn between the tastes of reviewers…and of readers! I think I understand the tastes of simpleminded folk (like myself) pretty well.”

While the Appendices unquestionably separate the serious wheat from the casual chaff, the 60 years since that letter have confirmed this sentiment. The Lord of the Rings remains something distinct — an epic fantasy novel that crosses literary and popular divides — because of the time Tolkien spent laying the foundations for that world. These Appendices may only provide a glimpse at the broader Legendarium that lurked beneath the surface, but — like the ship that ferried our heroes to the Undying Lands — they allow us safe passage to dig deeper in this hidden world.

When The Read Goes Ever On returns, it will be with some lighter fare: The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, featuring poetry from Middle-earth.

Image credits: City of Ost-in-Edhel Mural – Alan Lee & The first meeting of Arwen and Aragorn – Anke Eissmann