“Humans need snow to keep on living,” comments a narrator towards the end of Yoshigai Nao’s film. It’s an error: the subject meaning to say ‘heat.’ It’s what another artist fond of nature might have called a ‘happy accident,’ as this line almost singlehandedly taps into the essential conflict in this observational documentary.

Over the last few years, Yoshigai has been building towards the mid-length SHARI. When we last saw the filmmaker, dancer and choreographer, she took us into the floating world of Night Snorkeling (2021). Yet whether she it’s the gliding viewpoint of Wheel Music (2018) or presenting her short film Grand Bouquet (2019) at the Directors Fortnight in Cannes, the films Yoshigai calls ‘tactile’ have always demonstrated an understated and intuitive knowledge of the world moving around her.

Which brings her to Shiretoko Peninsula on the easternmost part of Japan’s Hokkaido, a spot registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. In a place where wildlife and humans coexist, Yoshigai encounters a winter of unusually little snow. Nevertheless, the concern citizens continue their lives. There’s the shepherd who runs the Baa Baa Bakery, while another couple look for squirrels in the backyard. The hunting of deer continues, and a man watches climbers on the nearby Mount Shari through his telescope.

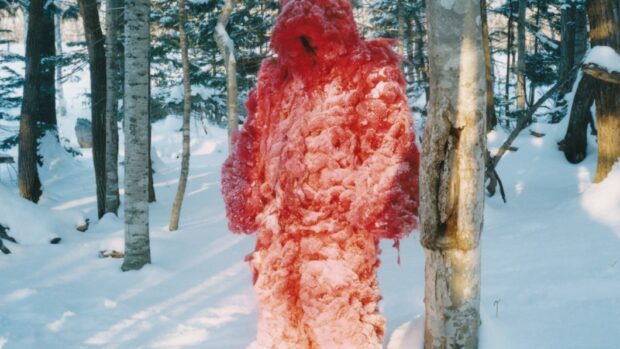

Yet much like the incursion of human activity on the environment, Yoshigai introduces something out of the ordinary. Yoshigai dresses in a red shaggy costume that leaves streaks wherever she goes. The costume serves as both an avatar and another rogue element in the delicate balance between humans and nature. There’s one sequence where the ‘creature’ chases some kids around a gym, unnervingly covering them in blood-like paint. Together they recreate stories of the Ainu, the First Nations peoples of Japan, including the story of Oronko Rock which is named for the people of the area.

Yoshigai’s choice of cinematographer is Naoki Ishikawa, a photographer, writer, and mountain climber who makes his feature film debut with SHARI. His skilled eye sees the world not simply in terms of perfect shots, of which there are many, but also in how each scene sits in the continuum of seasons. In a beautifully sequence from editor Miyako Daisuke, the blueberries of summer and subtly contrasted with the snow fields that dominate the rest of the film. Yoshigai’s dreamlike narration floats above it all.

Citing the seemingly endless fires in Australia, the point of Yoshigai’s film can almost be summed up in one resident’s comment: “It does make me think that something is off.” So, as the film ends with Japan heading into the Coronavirus pandemic, how does one even begin to face the overwhelming weight of it? As we watch Yoshigai stand on a mountain, strip off her red scarecrow of an outfit and let forth a primal scream into the endless ocean, we might just have our answer.

2021 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Yoshigai Nao | CINEMATOGRAPHY: Ishikawa Naoki | EDITOR: Miyako Daisuke | DISTRIBUTOR: CaRTe bLaNChe, International Film Festival Rotterdam 2022 (NL) | RUNNING TIME: 62 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 26 January – 6 February 2022 (IFFR)