When you think of Alice and animation, you tend to think of Disney. Their first star named Alice didn’t meet the Mad Hatter, but she did go to Wonderland.

Disney has declared that 2023 is their 100th anniversary. Yet 1923 didn’t start as a banner year for brothers Walt and Roy Disney, with the closure of their Laugh-O-Grams Studios.

Following the production of their earliest Newman Laugh-O-Grams in 1921, the Disneys and Ub Iwerks continued to work on the Laugh-O-Grams shorts the following year, and a series of now missing silent shorts called Lafflets.

Then they got to work on something new. A hybrid animation that combined a live action girl against an animated backdrop. Laugh-O-Gram Studios went bankrupt in early 1923, so Walt and Roy moved to California to form the Disney Brothers Studio on 16 October 1923.

Enter Alice

ALICE’S WONDERLAND was designed as a test cartoon. Shown to prospective film distributors but never shown theatrically, it’s hard to assess this by modern standards.

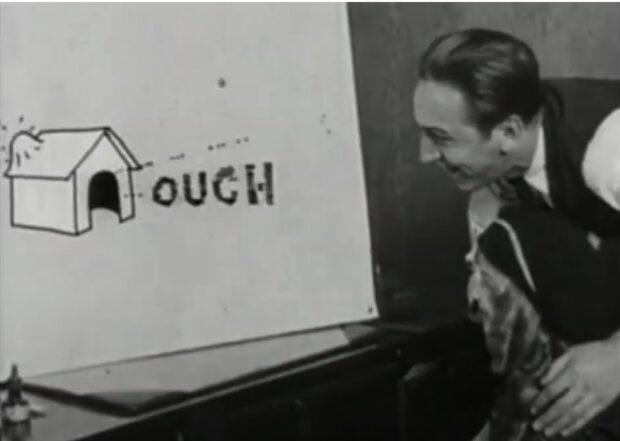

In the short, the titular Alice (child star Virginia Davis) visits the Laugh-O-Gram Studios where Walt and co. show her their etchings. She later dreams of entering a cartoon land, where she is greeted warmly, rides an elephant, and flees some lions who escaped from a zoo.

Borrowing the idea from Max Fleischer’s “Out Of The Inkwell” cartoons, Disney’s cartoon animals go through many of the same motions they did in contemporary pieces. Yet it ultimately sparked something with audiences, especially after M.J. Winkler picked up distribution rights to the shorts.

A total of 57 shorts, all directed by Walt, were produced between 1923 and 1927. Animators Ub Iwerks, Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, Carman Maxwell, and Isadore “Friz” Freleng honed their craft on these shorts.

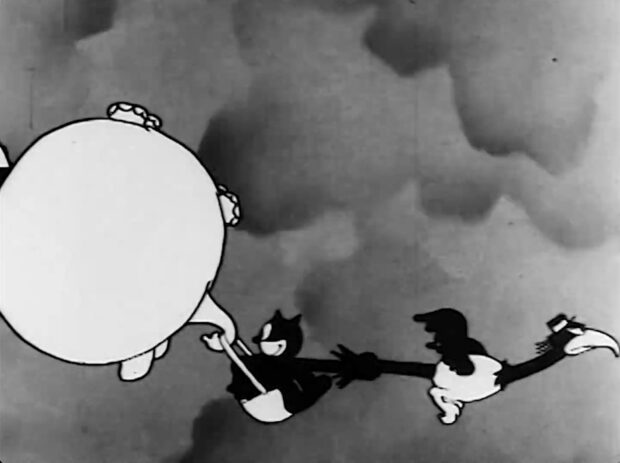

After the first 14 shorts, star Davis was succeeded by Margie Gay, Dawn O’Day, and Lois Hardwick. The character was regularly joined by Felixesque Julius the Cat, who had previously appeared in the Laugh-O-Gram shorts, making him the first recurring animated character in Disney’s oeuvre.

Contemporary views

Watching the Alice Comedies today is a bit of an endurance test. Given the the technical constraints and narrow storytelling parameters of the time, they become formulaic. Watching a bunch in rapid succession is not recommended. Indeed, even the second Alice short (Alice’s Day at Sea) is largely a redux of the first.

Some early highlights include Alice’s Spooky Adventure (1924), which ends with Alice rather unfairly being thrown in jail for the crime of retrieving a ball from an abandoned house. Sitting alone in a cell in her striped pyjamas, she laments “Isn’t it the troof (sic) — a woman always pays —” So it’s an early feminist work from Disney to boot!

Then there’s Alice and the Three Bears (1924), a film in which a bear makes homebrewed craft beer. (Does that make him a craft bear?) It’s a turning point for Disney: this doesn’t start with the framing device of Alice falling asleep, but instead introduces after several character moments of Baby Bear hunting for hops. (Trying to catch them from a frog in one of my favourite visual gags).

Looking for narrative in these shorts is folly: these are experimental shorts, and gag delivery devices to appeal to audiences. There are exceptions, of course. Alice’s Egg Plant (1925) is about Alice running a battery hen farm, but has a socialist core as the hens stage a small revolt. (It’s also the only time Dawn O’Day plays Alice).

Alice’s Balloon Race (1926) contains of the finest animation of the series, especially a climax in which Julius takes an elephant balloon into the clouds and rides a lighting bolt. It’s a classic example of animation literally breaking free of the bonds of earth and heading on up. Plus, any short that has a floating dachshund and a hippo smoking a pipe is worth its weight in gold.

Through a darker looking glass

The other issue when looking back at these shorts is dealing with the outdated tones of the past. Much of these are the racist and colonialist attitudes that era cinema took towards people of colour. Some are what Leonard Maltin one euphemistically called ‘antisocial behaviour.’

Alice Cans the Cannibals (1925) may as well be called Alice and the Colonialist Caper, as it is the very story of colonisation itself: a journey that goes off course, an immediate battle with the First Nations peoples of the land, and the ‘taming’ of the wilderness and its people. Filled with outdated stereotypes and overtly racist caricatures of the native populace, it’s an unfortunate trend that ran through Alice Chops the Suey (1925) and into the later Oswald shorts, multiple Mickey Mouse ‘toons, and beyond.

Some of these shorts take some seriously dark turns. Alice’s Mysterious Mystery (1926) features dog catchers dressed is what now conjure up visions of Klan outfits (although are actually ‘ghosts’). The same folks are kidnapping dogs to turn them into sausages! An especially disturbing scene sees one of the white-robed villains at the switch of a death chamber (!) for dogs, while one poor pupper begs and cries for mercy. Moments later, he is merely a link in a sausage chain. It’s the wurst!

Alice Solve the Puzzle (1925), in which an early version of Peg Leg Pete (or Bootleg Pete) pursues her, mirrors the storytelling of the early Oswald and Mickey shorts later on. This is the first animated film to be heavily censored, with the Pennsylvania Censorship Board asking Disney to remove a sequence in which Pete is stopped by a customs official and inspected for contraband. This was during the Prohibition after all.

Missing in action

Unfortunately for fans and completists, 16 of the 57 shorts have been lost to the ages. It’s especially frustrating that many of these are from the back half of Alice’s career, when Disney’s team was getting more confident and experimental with the material. In fact, of the last ten shorts only three are known to remain.

So, the final Alice short, Alice in the Big Leagues (1927), is actually one of the best. Now starring Lois Hardwick as Alice, it uses baseball as a motif, possibly for the first time since Alice’s Spooky Adventure. Some of the most inventive animation comes from the various animal friends’ attempts to get a view of the game through a hole in the fence.

Yet Alice proves to be as terrible at being an umpire as she is at pretty much everything else. It’s appropriate that in Alice’s final appearance, she is booed and chased off the field, morphing from live action to animation as she gets further away from the camera. It wouldn’t be until the 1940s, with The Reluctant Dragon (1941) and various wartime shorts, that Disney would regularly combine live action and animation again.

Vaulted

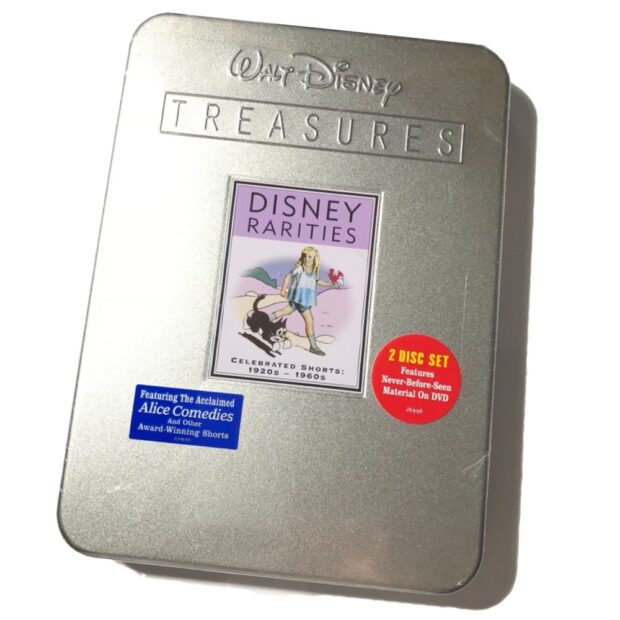

After passing into the public domain in 2000, various VHS and DVD releases began to emerge. So, Disney finally put out some official copies as part of the Walt Disney Treasures sets, including Disney Rarities: Celebrated Shorts: 1920s–1960s (in 2005) and The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (2007). Disney’s first princess briefly got to share the spotlight with Mickey, Donald, and Goofy.

Yet unlike her successor Oswald, Disney never revisited this version of Alice again. In 1933, Disney considered a hybrid Alice in Wonderland adaptation in the vein of the Alice Comedies, mixing star Mary Pickford with animated elements. They scrapped this in favour of work on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Disney’s second attempt at the story saw Walt file the film’s title with the MPPDA and hire storyboard artist Al Perkins and art director David S. Hall. A story reel was developed, but the high cost of their other features and the Second World War ended it. Disney’s Alice in Wonderland was eventually released in 1951. It remains a classic.

Disney Minus: I’m watching all of Disney’s available output from 1921 through to the present. My evolving watchlist is on Letterboxd, as are reviews for every single film I watch. Next: Oswald the (Not So) Lucky Rabbit

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot

All images in this article are owned by Disney unless stated otherwise.