“I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing — that it was all started by a small girl rabbit mouse.”

Back in 1927, Disney was at a crossroads. Cost and technical considerations brought the live action/animation hybrid Alice Comedies to an end.

Disney had just inked a one-year deal with Universal Pictures via Charles Mintz for a new Disney cartoon every two weeks. In exchange, they’d get national distribution, a step up from the states’ rights basis of Alice. Yet Universal wanted someone other than Julius, Disney’s Felix the Cat clone, to lead the shorts.

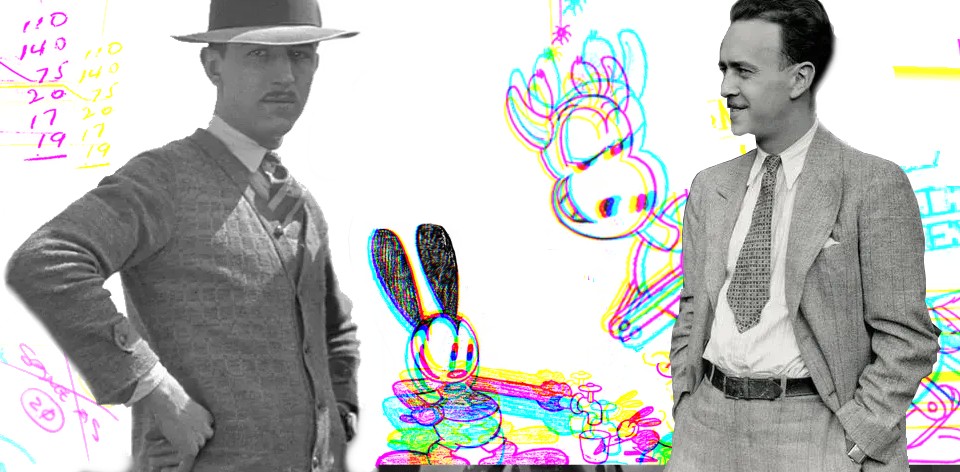

So, at the urging of Mintz, who didn’t want to compete with another cat character, Walt Disney was asked to create something new. With Ub Iwerks and Winkler Productions, Walt created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and produced the short film Poor Papa. Universal wasn’t happy with it, so Walt and Ub released the Trolley Troubles short first instead.

Oswald looks like a real contender…Funny how cartoon artists never hit on a rabbit before.

Film Daily, 1927

The gambit paid off, and Oswald suddenly rivalled Felix the Cat as one of the most popular animated characters in the world. There was even a five-cent candy bar, the ‘Oswald Milk Chocolate Frappe Bar’ from the Vogan Candy Company of Oregon, that become some of the first licensed merchandise from a Disney cartoon.

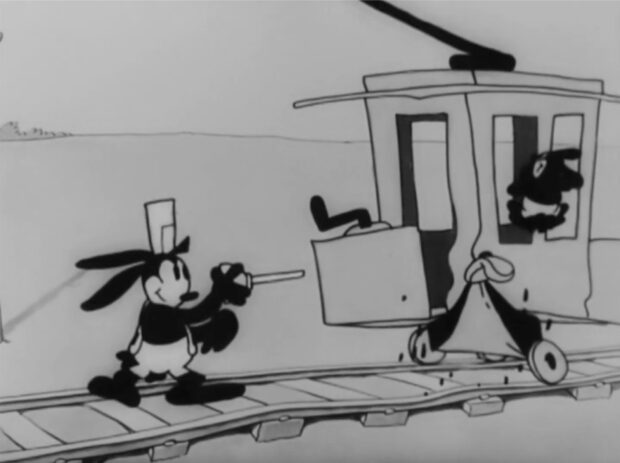

It’s easy to see why Trolley Troubles appealed. The primitive character designs are energetic, Oswald’s body is like a Swiss Army Knife and there’s some really innovative use of perspective in the tram sequences. In his wonderful biography of Walt Disney, Neal Gabler has catalogued commentary from animation historians, comparing Oswald’s body variously to Buster Keaton, inhabiting an animated form that was more conscious of the pleasures and pains of the body.

Oswald who?

For the uninitiated, Oswald is a hyperkinetic rabbity thing who succeeded Alice’s Julius the Cat and He appeared in almost 200 shorts throughout the 1920s and 1930s, although only the first 27 of these were made by Disney (for reasons we’ll get into later). Inspired by the silent film comedians of the era, he’s the immediate predecessor to Mickey Mouse, and so much of the Disney mascot’s DNA is in this ultimately unlucky lagomorph.

There’s a certain element of repetition to the early shorts, reworking concepts we’d already seen in the Alice Comedies. Oh Teacher (1927), for example, is a more sinister version of Alice Helps the Romance (1926) in which Oswald’s toxic masculinity is used to win the affections of his girlfriend by contemplating a bloody injury on a rival cat. The Mechanical Cow (1927) follows an early Disney tradition of cartoon animals riding a marionette ‘horse.’

Yet in each of the original Oswald shorts produced under the Disney name, we see the staff experimenting with the form. The animation staff — who at this stage included the likes of Walt, Ub Iwerks, Hugh Harman, Rollin Hamilton, Ben Clopton, Les Clark, and Friz Freleng — played with familiar themes but new techniques for the era. “The animators became increasingly skilled at more fluid movement, and the gags flew aplenty,” writes Tieman in The Disney Treasures.

In Great Guns (1927), there’s a wonderful opening where the camera irises in on the industrial cityscape as the film transitions from a declaration of war. All Wet (1927) sees Oswald and a customer grapple with an anthropomorphic hot dog, and has themes and techniques later reused in Mickey Mouse shorts The Karnival Kid and Wild Waves (both 1929).

As Oswald moves into 1928, there’s some especially clever stuff happening, some of which anticipates iconic later films. In Oh What a Knight (1928), our rabbit hero detaches from his own shadow (Peter Pan style) in order to sneak in a quick smooch with Ortensia before returning to the fight.

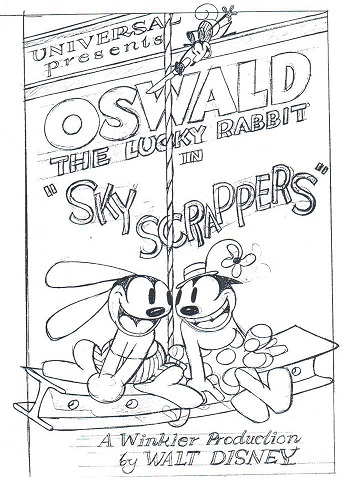

By the time we get to the final Oswald short, Sky Scrappers (1928), the team is far more confident with animation techniques. Oswald’s attempts to eat a lively hot dog (later reused in a Mickey toon) are priceless, as is the fight with an early version of ‘Pegleg’ Pete on a beam. Indeed, there’s a terrific use of perspective as the latter’s fist comes right at the audience. My favourite gag may have been Oswald pressing his belly button to restore his squished cartoon head.

Down the rabbit hole

As was the case with many of the Alice Comedies, and the later Mickey Mouse shorts and Silly Symphonies, there are depictions of race and gender that were wrong then and remain so today.

Bright Lights (1928), for example, not only features Mlle. Zuzu the Shimmy Queen but a brief depiction of blackface. Like Mickey, Oswald is very much rooted in the vaudeville traditions that used these insensitive gags as their stock in trade.

In Rival Romeos (1928), we see a goat chewing on what is meant to look like a pornographic magazine. Great Guns (1927), Poor Papa (1928) and Hungry Hoboes (1928) contain some gunplay and/or animal cruelty, not to mention the latter’s less than stellar title.

On the flip side, there are some that are missing or partially lost. The Banker’s Daughter, Rickety Gin, Harem Scarem, Sagebrush Sadie, Ride ’em Plowboy, while others only appear in part or in the depths of national archives. The search for them is chronicled in several texts.

Walt’s ‘betrayal’

Unfortunately for Walt and Ub, just as they were starting to gain some success in Hollywood, his first star was taken away from him.

Walt travelled to New York in 1928 on what he thought would be a simple renewal of their contract for a second series. Mintz, who had been the go-between for Disney and Universal, wanted to take over the studio with brother-in-law George Winkler. Without Walt’s knowledge, he offered the animators with job offers on the legal technicality that Universal owned Oswald. Walt had a simple choice: accept new terms with a reduction in income, or lose the rights to Oswald. Walt, never known for playing nice with others when backed into a corner, rejected the offer.

Oswald went on to his own success without Disney, with Universal producing more than 160 cartoons and multiple pieces of merchandise with the character until the late 1930s. Many of these are still available in the public domain today.

Walt and Iwerks? Well, legend tells of an infuriated Walt coming up with another character on the train ride home. Whether that story is apocryphal or not, by November 1928 they had debuted a new hero. He’s the guy they called little Mickey Mouse.

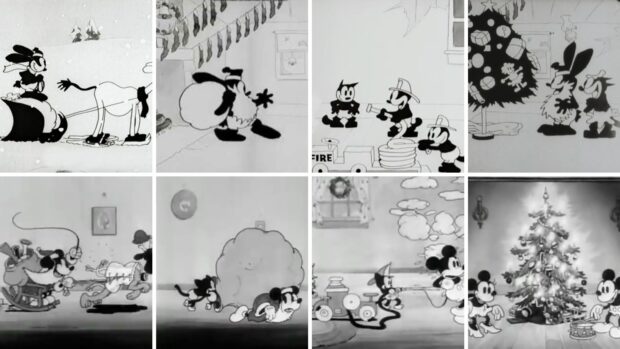

More than a trace of Oswald would still be found in Mickey Mouse. Apart from the similarity of design, Disney and Iwerks would continue to refine their ideas well into the 1930s. Mickey Mouse shorts Mickey’s Orphans (1931), Mickey’s Nightmare (1932), Ye Olden Days (1933) and Building a Building (1933) are just some of the Oswald shorts remade with Mickey Mouse. (See the image above for a sample comparison). Other gags would find their way into the later cartoons.

Oswald comes home

While Oswald could have been a mere footnote in Disney’s history, and was in fact largely ignored or only mentioned in brief in many biographies of the company, the unexpected happened some 78 years after Oswald and Walt parted ways.

In early 2006, Disney under Bob Iger initiated a deal to trade several minor assets with NBC Universal, including the rights to Oswald. In exchange, the parent company sent sportscaster Al Michaels from Disney’s ABC and ESPN to NBC Sports.

Since then, Disney has been reintegrating Oswald into cartoons, games, and parks. Oswald is a main character in the Epic Mickey video game franchise. He’s appeared in the short films Get a Horse! (2013), made character appearances in the theme parks around the world, and made appearances on the 2015-2018 Mickey Mouse series. At D23 Disney fan expo in 2017, the company celebrated 90 years of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.

As recently as 2022, you may have also seen a few seconds of Oswald in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness as they went tumbling through alternate realities. The same year, a brand new Oswald short was released for online audiences. Oswald is very much back in the Disney fold — and once again making money for them.

During a 2023 visit to a Disney Store in London, while I was putting the finishing touches to this article, I was thrilled to see a massive Oswald display at the entrance to the store on Oxford Street. Part of the Disney 100 celebrations, it was filled with spirit jerseys, leisure wear, plush toys, badges, mugs, and more. So, while the modern version of the company might maintain it was all started by a mouse, even they seem willing to admit that it’s the rabbit who has been the most resilient.

References

Bain, D., & Harris, B. S. (1977b). Mickey Mouse: Fifty Happy Years. New English Library.

Finch, C. (1999). The Art of Walt Disney. Harry N. Abrams.

Gabler, N. (2007). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage.

Gerstein, D., & Kaufman, J. B. (2022). Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse. The Ultimate History. Taschen.

Iwerks, L. (Director). (1999). The Hand Behind the Mouse: The Ub Iwerks Story. Walt Disney Pictures.

Kothenschulte, D. (2021). The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921-1968. Taschen.

Susanin, T. S. (2011). Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919-1928. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

Tieman, R. (2003). The Disney Treasures. Disney Editions.

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot

All images in this article are owned by Disney unless stated otherwise.