Bond. James Bond. In the 007 Case Files, join me as I read all of the James Bond books, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s spoilers ahead.

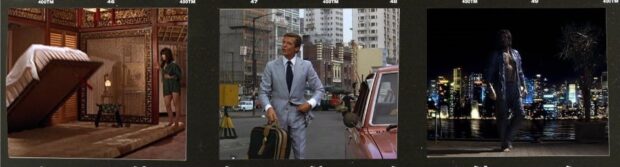

While Australian George ‘This Never Happened to the Other Fella’ Lazenby infamously played 007 just once, no James Bond film has been set here in the Antipodes. Benson’s debut Bond novel aimed to fix that, although the Colonial gaze is very much a part of this adventure.

Bond expert and continuation author Raymond Benson began his run in the pages of Playboy with the short story Blast from the Past, something I described as “something that he needed to get out of his system before moving onto more substantial Bond.” With ZERO MINUS TEN (1997) he does just that, harking back to an earlier age — and bringing some of the good and bad baggage with him in the process.

From our early 21st century perspective, the impact of the 1997 Handover of Hong Kong from British Colonial control to the People’s Republic of China is still very much a live issue. Benson uses the Handover — which had not yet occurred at the time of his writing — as the backdrop for his first major Bond adventure. Indeed, Benson’s working title for the book was No Tears for Hong Kong.

As the final title would imply, it’s ten days until the Handover and Bond is sent to Hong Kong to investigate a series of terrorist attacks. Bond thinks there are ties between shipping magnate Guy Thackeray, his company EurAsia Enterprises, and the criminal Triad organisations. At the same time, a nuclear blast goes off somewhere in the Western Australian outback, and you’re absolutely right if you think the two are somehow connected.

Benson’s plotting is based on a reliable formula, perhaps a conscious response to previous continuation author John Gardner’s highly technical manuals. There’s a sidekick in Hong Kong contact T.Y. Woo, a sex worker/hostess named Sunni Pei who needs rescuing, an intense game of chance — a game of Mahjong that may require you to learn more of the rules than I did — and a trio of villains each with their own agendas.

On this last level, it’s arguably a little overcooked. You’ve got Li Xu Nan, the head of the Triad organisation as the rightful heir to EurAsia Enterprises. There’s the corrupt PRC General Wong, attempting to claim the same for himself. In Thackery, you have something closer to a classic Bond megalomaniacal villain. In retaliation for losing EurAsia, he plans to dummy spit by detonating a nuclear bomb in Hong Kong so that it’s unlivable. It might speak to the complexity of interests at this crucial turning point in history, but it also feels like a lot of moving parts, especially in the closing chapters.

Benson’s approach to continuity may have purists clutching their pearls as well. Benson has previously stated he was given a licence to pillage whatever he wanted from Fleming, and Gardner’s bits were optional. Benson, for example, refers directly to characters introduced in Gardner’s Never Send Flowers, SeaFire, Scorpius, and Death is Forever. He acknowledges the female M introduces in GoldenEye and the cinematic universe, but has reduced Bond’s military rank back to Commander, the one he held under Fleming.

While it doesn’t make sense if you take all of Bond so far as one continuous story, it’s a smoother approach than Gardner’s. In the novelisation of Licence to Kill, for example, Gardner attempted to awkwardly marry Fleming’s and his own continuity with the films, resulting in Felix Leiter being canonically attacked for a second time by sharks. So, the ‘everything is real’ pick and mix approach might make this an Elseworlds ‘requel’ — if that kind of thing is important to you.

Still, even though time has passed, and there’s a funky fresh for the 90s set of hands behind the wheels, some things have apparently gone backwards. Benson’s plotting starts by acknowledging the crimes of Britain’s Colonial past, especially when it comes to Hong Kong and China. There’s a surprisingly nuanced analysis from Benson (via Bond) in acknowledging historical mistakes while spotting the realities of the present.

Yet somehow American author Benson ultimately adopts the same Colonial attitudes to First Nations peoples that the British did to both Hong Kong and Australia. Descriptions of what Bond using the term “Aborigines” – ones which I won’t replicate here – continue a tradition the British have exhibited since 1788. Bond is unsure if the people he encounters would speak English, for example. (Don’t get me started on his depictions of locals at an Aussie pub).

Benson would follow this only a few months later with Tomorrow Never Dies, a novelisation of the second Pierce Brosnan Bond film. Yet with its similar geography and cinematic outlook, ZERO MNUS TEN could have happily substituted as a Bond film of this era. Dated content aside, Benson’s Bond debut proper is a confident and assured piece, taking Bond into a new era while being unquestionably a part of the Fleming legacy.

James Bond will return…in Tomorrow Never Dies.