War! Education! Death! Disney embraces fast and efficient animation in a fight for survival on the international and home fronts.

“When Uncle Sam joined us on the lot, he brought with him a new and necessary institution,” says The Ropes at Disney, an illustrated manual given to employees in 1943. “We refer, of course, to the identification badge.”

“The point is (and we aren’t kidding) you can’t get through the time office, morning or night, without your badge.” It was a sign of the times at Disney, n indicator that the first two decades of artistic experimentation had given way to something else. A world war, strikes, commercial disappointments, and a vastly changed roster of staff had ended the first Golden Age.

Yet there are few years in the century of Disney history that are as quietly significant as 1943. It had been 20 years since Laugh-O-Gram Studio went bankrupt and Walt and Roy founded the Disney Brothers studio. Two decades later, Disney was once again facing a financial and creative crisis.

No major animated classics were released that year, yet it produced some of Disney’s most intriguing animation. Their output at this time was prolific, and yet only two short films from 1943 are currently on Disney+. While the world was at war, the spirit of 1943 saw educational shorts, propaganda, and iconic debuts in equal measure.

Prelude to war

The 1940s had already been a tumultuous decade for Disney. Following the financial disappointments of Fantasia and even Bambi, together with the protracted animators’ strike of 1941 changing the culture of the studio, Walt probably jumped at the chance to get some guaranteed contracts.

Those chances came in the form of government work. In 1941, the United States Department of State and the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA) asked Disney to do a goodwill tour of South America as part of the Good Neighbor Program. At the time, the US was afraid that certain parts of Latin America leaned towards the Axis, and wished to use cultural ties to strengthen Latin American connections.

Walt and about 20 artists got a trip around South America, and any films would be guaranteed by the government. This last bit was especially good for the cash strapped studio, resulting in films like Saludos Amigos (1942), The Three Caballeros (1944), and some of Disney’s first forays into educational short films.

Yet by the end of 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the US entered the war. Disney was already making films to sell Canadian war bonds, such as The Thrifty Pig. By 1942, the army had literally moved into their offices to protect the nearby Lockheed base, around which time Walt made Ice Formation on Aircraft as a technical proof of concept for military training videos. That same year, Disney used Donald Duck to get people to file their taxes on time in The New Spirit, a film that the Gallup poll estimated was seen by around 60 million people.

The experiment paid off in a way. “In 1943, the studio had only slipped further into the war morass, had only become more a defense factory and less of a movie studio,” writes Neal Gabler in Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006). “Ninety-four percent of the output now went to the government, and in June 1943 alone the studio produced just 2,300 feet less film than it had produced in all of 1941.”

It kept the financial wolves off the doorstep for a time, but was it any good?

The Spirit of ‘43

The tone of 1943 was set early with Der Fuehrer’s Face, also known as the one where Donald Duck is a Nazi — albeit a highly reluctant one. Originally titled Donald in Naziland, the name was changed thanks to the runaway success of an eponymous song by Oliver Wallace, popularised by Spike Jones.

The short film lands in an America at total war and under intense rationing. So, the lampooning of life in “Nutzi Land” was twofold: it poked at the enemy as fair game, using racial caricatures of the Germans and Japanese, and broad humour to diminish their power. It was also meant to show just how much worse oppression was under the German dictatorship, characterised by Donald being punished by a pre-I Love Lucy production line.

It features a surreal dancing shell sequence that is nightmare fuel, like a dark and twisted version of Dumbo’s pink elephant scene. Culminating with Donald waking up back at home declaring “Am I glad to be a citizen of the United States of America” – and a tomato to the face of Hitler – the audience are invited for one last sing-a-long. (Now try to sleep with the added image of thousands of 1940s children singing a song about Hitler).

With Education for Death, based on a book by Gregor Ziemer and subtitled ‘The Making of the Nazi’, it’s fair to say Disney has rarely delivered a more chilling cartoon. “What makes a Nazi?” asks narrator Art Smith in the opening scene, with a dramatic zoom in on a symbol of hate. From the birth of a German boy through to his service as a soldier, this is the more serious twin to the comical Der Fuehrer’s Face. While there are scenes played for comedy – specifically the scenes of Hitler in knight’s armour taking Germany for a “ride” – this is as dark a narrative as they come.

Using caricature, here Disney’s first adaptation of Sleeping Beauty is reframed as the fairytale Hitler tells the German people. The journey of the aforementioned boy traces the naming laws, the erasure of empathy from children and their parents, and the breeding of a hatred for any sign of difference.

The final moments of this film are legitimately terrifying. Following a montage of book burning and cultural replacement, we see the horrific vision of German soldiers marching in unison, their multitude of faces obscured by human-sized dog muzzles, before all being replaced by graves on a battlefield. It’s grim stuff.

By contrast, if Reason and Emotion was released outside the narrow confines of the wartime efforts, it would probably be considered one of Disney’s greats. It is unquestionably a piece of propaganda in this unedited form, but it’s also got one of the most enduring motifs in entertainment – that is, peering at the personalities inside people’s heads.

Inspiring Inside Out and Herman’s Head in equal measure, there are still elements of this that very much date the film in 1943. When the Man spots a woman passing by, there’s some thoughts that may not fly in Disney’s 2023 oeuvre, suggesting that this was probably made for adults at the time. For a comparative look inside the mind of a woman, the narrator asks “May we borrow your pretty head for a moment?” While in there, we see the struggle is between hunger and reason. “Uncontrolled emotion can cause you a lot of trouble,” says the narrator, and the visuals tell us he means ‘being fat.’

The crux of the propaganda elements come with the introduction of a man stressed out by all the rumours he is hearing about the war. Personified as ghosts, these wonderful animated non sequiturs demonstrate that unchecked emotion can lead to you being easily controlled. The short then overtly uses Hitler’s Germany as a comparison, making this a companion piece to Education for Death. The German is portrayed as a reasonless leader spitting out words, suppressing reason, and leading by “fear of the concentration camp, fear of the Gestapo.” Like Chicken Little, released at the tail end of 1943 as an allegory for fear mongering, this film that was drafted a dissection of Nazi propaganda. Subtle they are not, but it is effective imagery for a wartime nation.

Familiar characters continued their adventures during the war as well. Donald signed up for service in 1942 with Donald Gets Drafted, and Disney followed that over the course of six or so shorts, including the very funny Fall Out – Fall In. Alongside Donald’s adventures in Nutziland, he returned to explain the benefit of saving for taxes to beat the Axis in The Spirit of ‘43, got plagued by Spike the Bee (and his nephews) while spotting aircraft in Home Defense, and battled rubber rationing in Donald’s Tire Troubles. It’s possible his hijinks in The Old Army Game, in which Donald holds a gun to his own head, may have got him kicked out of the armed forces.

Fading star Mickey really only appeared once in 1943 in the Uruguay-set Pluto and the Armadillo, another product of the CIAA initiative, and he’s outshone by his titular costars. Goofy did his bit for the home front by showcasing a range of ridiculous but hilarious forms of transport in Victory Vehicles — complete with the catchy tune, ‘Hop on Your Pogo Stick.’ Even Pluto signed up in Private Pluto, battling a pair of chipmunks and making 1943 significant as the debut year of Chip ‘n Dale.

Road Dahl’s The Gremlins

One of the most famous film productions from the year was ultimately one that didn’t get made. The Gremlins was penned by a recognisable name: Flight Lieutenant Roald Dahl. Yes, two decades before James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, this was Dahl’s very first book for children. With cover art by Mary Blair, and illustrations from an uncredited Bill Justice and Al Dempster, it tells the story of the titular critters spotted by RAF pilots drilling holes on the wings of their planes. Originally intended to be filmed as a feature, 50,000 copies were printed in the US, although a paper shortage prevented a quick reprint. Thanks in part to questions around rights, and Dahl’s insistence on script approval, the film itself never eventuated. Warner’s Bugs Bunny short Falling Hare came out the same year with a similar premise.

Victory Through Air Power

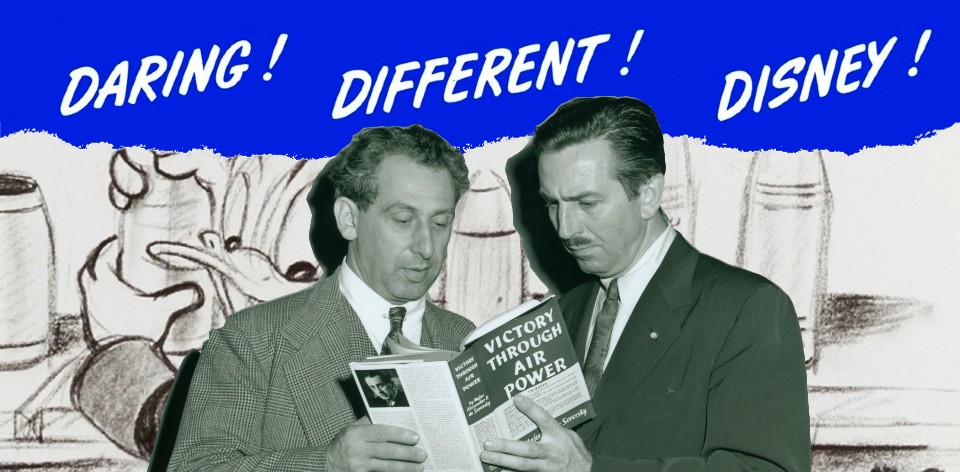

While The Gremlins film didn’t eventuate, another adaptation came about from an unlikely source.

“The most significant single fact about the war now in progress is the emergence of aviation as the paramount and decisive factor in warmaking,” said Russian-American aviation pioneer Alexander P. de Seversky in his book Victory Through Air Power. He goes on to describe the devastating impact of New York, Detroit, Chicago, and San Francisco “reduced to rubble heaps in the first twenty-four hours” of an enemy attack. His fundamental understanding was that the nature of war had changed. “There is just one target: the whole country.” In other words, the US needed a dedicated air force.

It was a very persuasive argument. So much so that the studio’s only feature film released for the war effort came about as something of a passion project by Walt Disney. Based on the Seversky’s book, Walt was so convinced by its tenets that he is said to have personally financed the animation in this film. As Leonard Maltin said in a 2004 DVD introduction, “Walt quite simply put his money where his mouth was.”

In the canon of war time Disney films, Victory Through Air Power is distinct not just for its length, but for trying to be both educational and entertaining. It has a point to make: it’s right there in the title. Yet this doesn’t stop Disney from bringing the drama at every turn. As the trailer for this film claims, it’s a “thrilling graphic visualisation of the book.” Walt rushed this into production to visualise the urgency of the otherwise abstract notion of aerial warfare.

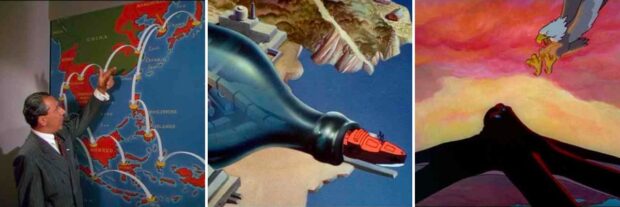

Yet it’s the pure animation where the film is at its most effective. The problem with relying on shipping is shown by animating an actual giant bottleneck. Animated maps dominated by symbols of the axis show the potential of their reach with tentacles wrapped around the globe. Envisaging the war going into 1947 and 1948, the film makes a case for a “highway to victory” running through Alaska. Few audiences in the era would blink an eye at the offensive depictions of Germans and the Japanese, and they are used here with unrelenting intent.

The final moments of the film are the most powerful, lifting Seversky’s prognostications of doom right off the page and into animated reality. Bombs dropped from above drill deep into the Earth, smashing cities. Like some kind of early kaiju film, a giant eagle fights an equally large octopus before landing atop an American flag. Sure, it’s obvious propaganda, but it bears repeating: it’s 1943 and the world is at war.

The result was tangible, and both Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly requested prints and were ultimately convinced by its message. Plus, American citizens were given a theatrical bit of edutainment to wrap their support around.

The films that built a hemisphere

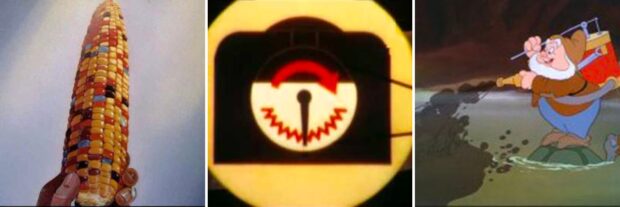

In some cases, this was merely technical diagrams and maps for army training films, like the Aerology series for Lockheed and the military. These included films like the Theory of the C-1 Autopilot, Aircraft Wood Repair and dozens of hours of dry animation that peppered training productions. In the case of Electronic Control System of the C-1 Auto Pilot Part 1: Basic Electricity, Disney developed whole animated characters like Mr. Volt and Mr. Current to explain how electricity works.

Continuing their work with the government in Latin American relationships for the CIAA, health films like The Grain That Built a Hemisphere, Water: Friend or Enemy? and The Winged Scourge (with a Seven Dwarfs cameo) provided important health information while providing some eye-catching but cost-efficient animation. Highly realistic figures and objects – often assigned to animators like Bill Tytla, Josh Meador, and Ed Aardal – gave all of these a unique look and feel.

A personal favourite from the year is Defense Against Invasion, designed to teach people about how vaccines work. If the last few years have shown us anything, it’s that this has become super topical again.

The film is a live action/animated hybrid explaining how the immune system works and the way vaccines enter the body. If you’re familiar with the modern anime Cells at Work!, this will seem retroactively familiar. There’s a little model city inside the body, where disease acts as a saboteur of the hard working factory cells. In the context of global armed conflict, vaccines act as an analogy for a well-armed defence force.

“The death rattle of the vaccine guns are heard on all sides.” Indeed, there’s Itchy and Scratchy levels of violence on display here. A whole tiny army and air force of good cells are built to fight the invading disease, drawing a line between surface contact and airborne diseases. The wartime analogies notwithstanding, it’s all very familiar territory in this post-pandemic era, with animation that feels fresh and modern.

Legacy of ‘43

“It is not visionary or presumptuous for us to anticipate the use of our own medium in the curriculum of every schoolroom in the world,” Walt Disney said in 1943.

Any child who sat through The Story of Menstruation, the Upjohn Triangle of Health Series, or Jiminy Cricket’s life lessons can attest to this. Chances are pretty good that somewhere between the 60s and 80s you watched a film reel or video that gave your teacher a chance to have a quick nap up the back. More than anything, 1943 solidified Disney’s reputation for delivering cost effective and influential educational animation.

While it is obvious why Disney hasn’t stuck much of the year’s output up on their flagship streaming service, nor much of anything in the way of an official release since Walt Disney Treasures: On the Front Lines DVDs in 2004, there’s a goldmine of animation styles and content for those willing to go digging.

Disney would spend the better part of the decade making package features and compilation films, continuing their educational work through commercial and government fare, and branching further into live action and hybrid features. So, while ‘Disney 20’ may not be as sexy as the Disney 100 campaign, it remains an important archive of a point in time and a crucial turning point for a creative company.

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot

All images in this article are owned by Disney unless stated otherwise.