Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases a very slow re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

As you work your way through any writings about Tolkien, especially those in relation to the writing or publishing of his literature, you inevitably come across references to his letters. In fact, most articles in this column have noted them in some way. A prodigious correspondent for his whole life, albeit an often beleaguered one, when collected together these letters form a kind of informal memoir or autobiography.

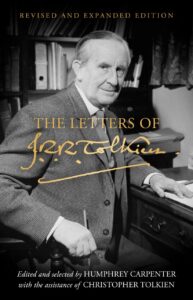

First collated and published by biographer Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien in 1981, the book contains over 350 letters spanning from his undergraduate days in October 1914 through to 29 August 1973, just four days before his death. In November 2023, a revised and expanded edition took this number up to 500, giving the world an additional 50,000 words by Tolkien.

Until this new edition came out, I had largely used the letters as reference material. When I was re-reading The Hobbit, for example, I was fascinated to find his 1955 correspondence with W.H. Auden where he declared “On a blank leaf I scrawled: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ I did not and do not know why.”

Yet the timing of this revised copy – coming so soon after my explorations of some of the First and Second Age writings compiled by C. Tolkien and beyond – was too good to pass up as a complete text. From his earliest days through the trenches, his formative relationships with wife Edith and his Oxford chums (including C.S. Lewis), through to the publication of his famous works, the letters are alternatively insightful, intimate, charming, naive, cantankerous and dismissive. In other words, they paint Tolkien as a complete human.

There seems to be a running thread for decades that Tolkien can’t seem to get started or finished on something due to an illness, either his own or his wife’s. Indeed, there are times when you feel like Tolkien was coming in or out of the flu on a weekly basis between 1938 and 1973. If not that, it’s his Oxford work getting in the way of his Middle-Earth studies – and vice versa. Writing to Michael Salmon in 1972 (Letter #335), a year before Tolkien passed, he remarked that “Every extra task however small diminishes my chance of ever publishing The Silmarillion.”

The essential Letter 131, in which Tolkien outlines the entirety of his saga of jewels and rings to publisher Milton Waldman (after Allen & Unwin declined to publish The Lord of the Rings together with The Silmarillion) is now 40% longer in the 2023 edition, giving readers a complete summary of Tolkien’s grand vision. Apart from being one of the few written examples of Tolkien’s whole vision of his grand Legendarium, it serves as a tantalising taste of an alternate timeline where the whole damn thing was a single volume. Bookshelves and backpacks everywhere will be grateful, but readers will always wonder ‘what if.’

While there is sadly still very little material surviving between 1918 and 1937, meaning the development of The Hobbit and The Silmarillion is not covered as thoroughly, the collection is brimming with moments that make Tolkien the man almost as fascinating as the characters in his writings. His love for his wife Edith and his children comes through strongly, as does his faith and Christianity. We get to see Tolkien’s frank opinions about publishing to Allen & Unwin. He is someone who takes the time to respond to ‘fans’ with lengthy answers to their questions.

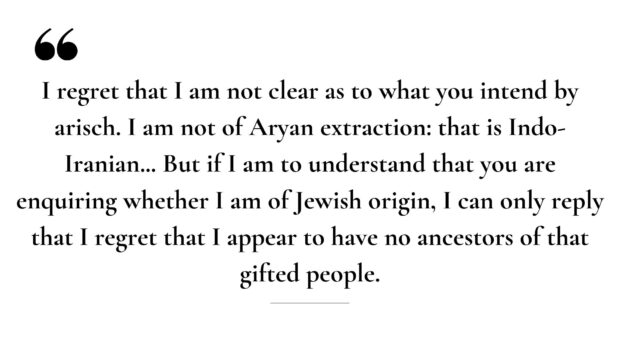

The infamous Letters 29 and 30, penned in 1938, in which he reads German publishers for filth over the racist implications of questions about his Arisch (Aryan) origin, might make you want to stand up and applaud. In 1944, writing to his son Christopher, he objects to the British press denigrating the German people, effectively arguing that it is the tactic of the enemy (Letter #81), and also decries the racist policies of his birthplace, South Africa (Letter #61).

Which is why this remains such a valuable collection. Compared to the technical perfections he chose in his published works, this is Tolkien at his most unguarded. There’s a heartbreaking moment in a letter to Christopher in 1972 (Letter #340), writing about Edith’s passing the year before.

“I have at last got busy about Mummy’s grave… The inscription I should like is:

EDITH MARY TOLKIEN

1889-1971

Lúthien

: brief and jejune, except for Lúthien, which says for me more than a multitude of words: for she was (and knew she was) my Lúthien.”

While some of this came through in the 2019 biopic Tolkien — directed by Dome Karukoski and starring Nicholas Hoult and Lily Collins as Tolkien and Edith respectively — that work misses the nuance that only contemporaneous personal correspondence can fill. At the time of release, I said that while “there is nothing necessarily inaccurate in the content [of the film], every moment is so layered with symbolism as to make it sometimes feel like a work of fiction.” Or, if we want to borrow Alfred Hitchcock’s adage about drama being life with the dull bits cut out, then this volume proves that a complete life requires those boring bits.

At the end of the day, THE LETTERS OF J.R.R. TOLKIEN probably works better as a reference work rather than an ‘autobiography’ per se. Yet the type of reader who will be drawn to this is inevitably someone who is used to reading Tolkien’s extensive sagas, and piecing together all of his thoughts to form a more complete picture in their minds. Perhaps more letters will one day be found and released, but until then this remains a vital document for scholars and fans.

In the last column, I have been bidding ‘Namárië’ in the last few columns, and it has been well over a year since I last wrote anything about Tolkien. These letters have certainly re-sparked my interests in Tolkien’s writings, so one suspects the sun will not set on 2024 without another one of these.