Disney’s JOHNNY TREMAIN (1957) is a film that embodies the often conflicting values of 1950s Americana and the revolutionary spirit of 1776.

Having not been raised on tales of the Revolutionary War and the like, my reference points have largely been the musical Hamilton and that comment Bart Simpson made about a potential alternate title for Esther Forbes’s 1943 novel, Johnny Tremain. That 1993 episode, Whacking Day, is a satire of the kind of mythologising that’s so present in this 1950s Disney film.

For those unfamiliar with the source material, this film doesn’t provide extensive background information. It opens in 1773, just after Great Britain passed the Tea Act. This legislation granted the British East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies, undermining local merchants and asserting British control over colonial trade.

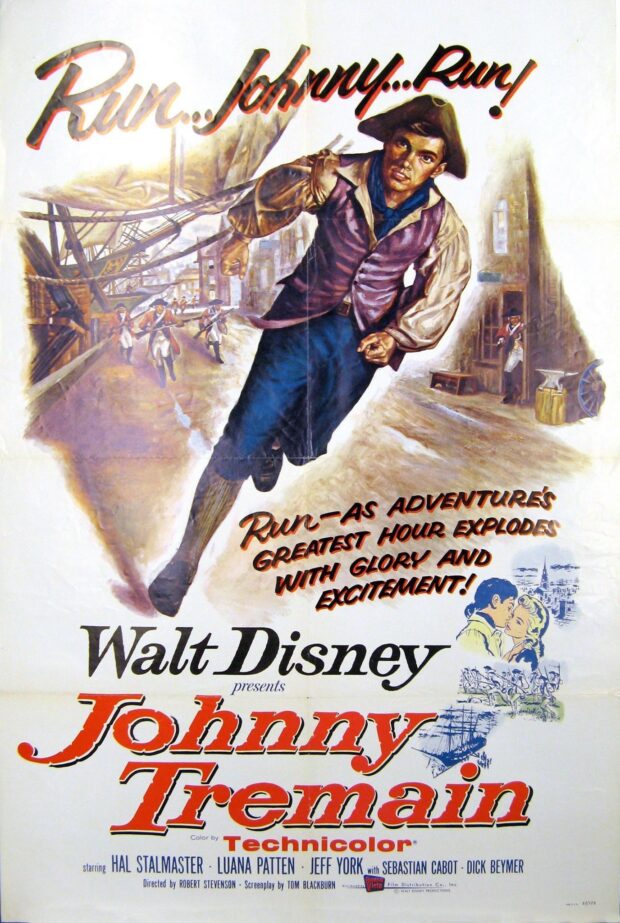

During this time, Johnny Tremain (played by Hal Stalmaster) is apprenticed to a silversmith. As his master Lapham refuses to do small jobs, Tremain is forced to work beyond his abilities and is severely injured as a result.

Unable to secure regular work, Tremain falls in with the Sons of Liberty, an underground organisation with the aim of advancing the interests of the original thirteen Colonies. As a message runner, Tremain becomes involved in key moments in pre-Revolution history, including the Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride and the first engagements of the American Revolution.

Cold revolution

Disney’s JOHNNY TREMAIN sits at a curious junction, one where more overt Americana and faith-based ideals are taking on more prominence in films like So Dear to My Heart (1948), Westward Ho, The Wagons (1956) and even in documentaries Antarctica: Operation Deep Freeze and Lapland. This was, after all, only a year after “In God We Trust” became the official motto of the United States. During the Cold War, it was a way to contrast the religious values of the United States with the atheistic ideology of the Soviet Union.

Yet the 1776 ‘revolutionary spirit’ is conversely about rejecting the pillars of the old world. There’s an early scene in the film where Tremain and his friends break the Sabbath to do some metal work. For this, Tremain is immediately ‘punished’ with a life-altered injury (As Bart reductively says, “They should call this book Johnny Deformed.“). The rest of the narrative is essentially about Tremain’s redemption, achieved by embracing collective principals over individual profit.

Which perhaps is what makes Tremain so rigid a watching experience today. It’s positively steeped in the values of an era, while being nostalgic about the ideals of another. You could almost apply that observation to Disney of the 1950s more generally, for what is Disneyland if not a mid-century rose-coloured vision of the way America ‘used to’ and ‘might’ be? An excellent cast of people like Jeff York, Luana Patten, Sebastian Cabot and a very young Richard Beymer (West Side Story, Twin Peaks) talk almost entirely in speechifying phrases, robbing them of the chance to show any individual charm.

Patten (Song of the South, Fun and Fancy Free, Melody Time, So Dear to My Heart), York (The Great Locomotive Chase, Davy Crockett) and Cabot (Westward Ho, The Wagons and beyond) were all part of Disney’s growing rep company, yet Tremain himself is played by relative newcomer Hal Stalmaster. The young actor was brother of legendary casting director Lynn Stalmaster (according to D23’s Jim Fanning), and it’s unusual that one of the Mousketeers or Mickey Mouse Club serial stars weren’t cast instead.

On a technical level, despite being originally shot for a two-part Disneyland anthology episode (but later released theatrically), Charles P. Boyle maintains his usual high standard of Technicolor photography, with the skirmishes and battles slickly captured. Like the megahit Davy Crockett series, Walt understood that filming in color would not only allow for theatrical re-releases but also ensure the film’s longevity. However, even with a series of songs (including the catchy ‘The Liberty Tree’), the second half of the film feels somewhat repetitive, even within its brief 80-minute runtime. It all concludes with a big ol’ painting of Boston burning, accompanied by a heavy dose of metaphors about fire and freedom.

A story that never ends

Curiously, Disney had planned to spin this out into a Liberty Street section of Disneyland shortly after the release of the film. The televised The Liberty Story even showed the plans for it to millions of viewers. Yet that didn’t eventuate in the California park. It eventually morphed into Liberty Square in Walt Disney World in the 1970s – a few years before the bicentenary of the events depicted here.

The other legacy is, of course, director Robert Stevenson. Following a short hiatus, this film marked the veteran screenwriter and director’s first film with Disney. You may not guess it from the the final product, but it was a relationship that would last with the studio for 20 years — and almost as many films. Stevenson followed this with the traumatic Old Yeller the same year, and added Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Mary Poppins (1964), The Love Bug (1968) and Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) to his filmography in the years that followed. It’s no wonder Disney posthumously named him a Legend in 2002.

JOHNNY TREMAIN may not be one of Disney’s more memorable classics, but it played a crucial role in solidifying the studio’s interest in promoting a specific brand of Americana. This theme continued with productions like The Swamp Fox, where Stalmaster appeared alongside Leslie Nielsen as Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion. Today, this focus on American heritage is still evident, particularly in EPCOT, where the message has been distilled into three simple words: “The American Adventure” — now with the added charm of merchandise, Muppets and a touch of commercial flair.

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot