By the 1950s, the Western had swaggered its way to the top of American cinema, riding high since the dawn of the silver screen. Disney, never one to miss a trailblazing opportunity, saddled up and delivered nearly 30 productions across film and TV, carving its own niche into the genre’s storied landscape.

Disney wasn’t just jumping on the Western wagon train either. From their animated shorts to live-action features and first forays into television, the Western was baked into the DNA of their output.

By 1954, when Disney introduced the idea of his eponymous theme park to audiences, the Western-themed Frontierland became a cornerstone of both the Disneyland TV show and the park itself, which opened the following year. Disney didn’t just dabble in the genre—they made it their own.

Animated beginnings: rabbits on the range

Disney’s earliest animated offerings were often groundbreaking experiments with the form, yet they weren’t created in a bubble. They reflected popular culture as much as they created it and Westerns had been part of film culture from the beginning. From early animated antics to more genre-specific works, Disney gradually embraced the Western, blending folklore, humour, and frontier ideals along the way.

Disney’s earliest animated offerings were groundbreaking experiments with form, yet they reflected popular culture as much as they shaped it. Westerns had been part of film since the beginning, and Disney gradually embraced the genre, blending folklore, humour, and frontier ideals.

Early Western motifs appeared in the Alice Comedies and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts—like Alice’s Wild West Show (1924) and Sagebrush Sadie (1928)—where the frontier served as a playground for slapstick. Mickey Mouse followed suit with The Cactus Kid (1930) and Two-Gun Mickey (1934), laying the groundwork for Disney’s later embrace of Western folklore.

By the mid-1940s, Disney leaned more heavily into the genre with Goofy’s Californy ’Er Bust and Pluto’s The Legend of Coyote Rock. The Pecos Bill sequence in Melody Time (1948) completed the ’40s formula for capturing the fun, mythical side of the Old West.

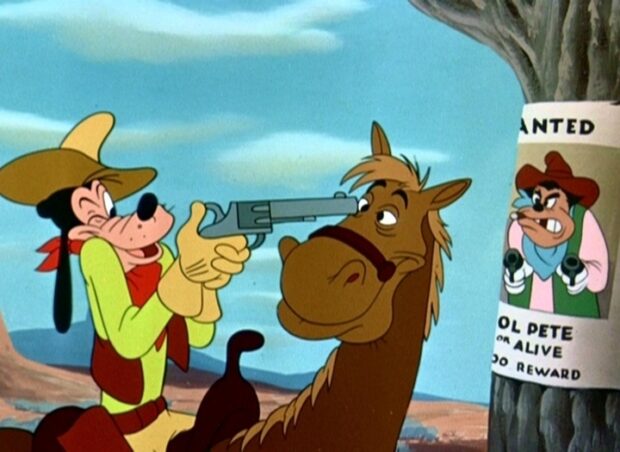

Later shorts, like Pests of the West (1950) and Two Gun Goofy (1952), took cues from Warner Bros., ramping up the cartoonish chaos. The final act of Two Gun Goofy feels like Bugs Bunny might be lurking just offscreen, orchestrating the chaos. One of my favourites is The Lone Chipmunks (1954), where Chip and Dale face off against outlaw Pete. It’s wonderfully silly: at one point, Pete accidentally uses Dale as a gun, who lets out an appropriately squeaky ‘bang’.

With layout styling by Xavier Atencio, later famed for Pirates of the Caribbean and The Haunted Mansion rides, the UPA-style A Cowboy Needs a Horse (1956) is visually striking, featuring mid-century modern designs and vivid, impressionistic backgrounds by Ralph Hulett and Al Dempster. Paired with cowboy docudrama Cow Dog (1956) and Secrets of Life on release, the film revolves around a catchy song that still sticks days later. However, the stereotypical depiction of First Nations peoples, though featuring dynamic visuals, detracts from the otherwise charming and beautifully crafted animation.

Kings of the wild frontier: Davy Crockett and the small screen

Disney’s Davy Crockett (played by newcomer Fess Parker) was a legitimate cultural phenomenon. Between the coonskin caps and other merchandise—not to mention the wildly popular theme song—the Crockett Craze generated over $300 million in sales during its first year. (That’s about $3.5 billion in today’s money—from just three TV episodes.) Even Back to the Future couldn’t resist: when Marty McFly heads back to 1955, both the song and the cap turn up on screen. The success completely caught Disney by surprise.

In many ways, the studio spent the rest of the decade trying to recapture this lightning in a bottle. Crockett himself starred in five episodes of the Disneyland anthology show, and two compilation features followed. The six-part Saga of Andy Burnett was very much made in the Crockett mould, with Jeff York (who played Mike Fink in the Crockett episodes) returning. While Zorro was not strictly a “Western,” its frontier setting of Spanish California and swashbuckling hero (played by Guy Williams) became iconic.

Combined with the The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca serial, starring Robert Loggia as the true-life gunslinger turned lawyer and politician, we can now acknowledge that Disney created two iconic Hispanic screen action heroes in the late 1950s. A similar approach was taken with the more expansive Texas John Slaughter chronicles, based on the real-life Texas Ranger. It may not be Disney’s most memorable western, but it’s a solid entry with standout moments, especially in the Sandoval two-parter featuring Beverly Garland’s Amanda Barko.

Even the daily episodes of the more kid-centric Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959) reflected the popularity of the Western trend. Talent Round-up Day on Fridays saw the Mouseketeers dressed in cowboy outfits, with a cartoon Mickey in Western garb a prominent part of the logos. Serials story Corky and White Shadow put a young girl in the centre of a Western tale, while the more successful Spin and Marty gave audiences a modern take as the title characters spend their summers at the Triple R Ranch.

The success of Disney’s Westerns on television cemented their role in helping shape mid-century American ideas about the West, particularly through serialised storytelling that kept audiences hooked week to week.

Cowboys and cultural clashes on the big screen

Disney’s 1950s big-screen Westerns often featured plenty of horse-bound action. From Stormy, The Thoroughbred (1954) to the small-scale The Littlest Outlaw (1955), Disney used documentary techniques to shape these narrative stories—what we might call slice-of-life docudramas today.

Disney didn’t just entertain; their Westerns offered a family-friendly, packaged version of frontier life, often highlighting historical figures whose stories reflected themes of exploration, heroism, and morality. The Great Locomotive Chase (1956) captures this with an almost aggressively centrist retelling of Andrews’ Raiders and Hunter’s Confederate conductor—likely a reason it remains less heralded among Disney’s 1950s output (though Walt’s own love of trains is evident throughout).

These adventures didn’t ignore First Nations perspectives, although portrayals often leaned on cultural stereotypes of the time. Peter Pan (1953) remains one of Disney’s beloved films of the era, yet its song “What Makes the Red Man Red” and Ward Kimball’s caricatured Chief have aged poorly. Westward Ho, The Wagons! (1956) similarly attempts authenticity, with the Disneyland behind-the-scenes episode Along the Oregon Trail detailing Sioux consultations for language accuracy. Still, the film ends anticlimactically, caught in a last-minute crisis and a literal white saviour narrative.

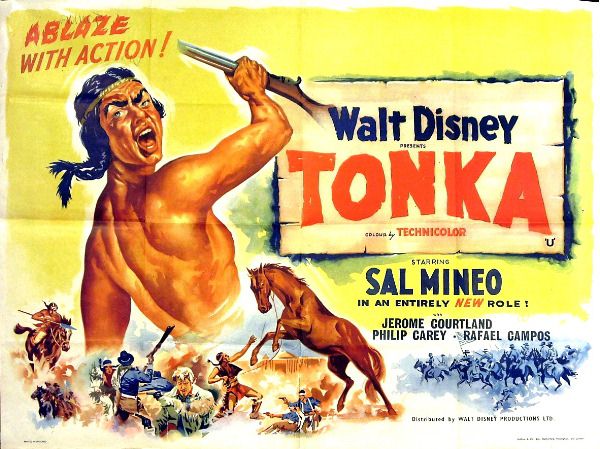

More considered attempts came with Tonka and The Light in the Forest (both 1958). Tonka follows White Bull, a young Teton Sioux played by Italian-American Sal Mineo, highlighting era-specific casting biases. The film acknowledges traditional practices and even portrays General Custer as a villain, though it ultimately leaves conflicts unresolved. The Light in the Forest delves into Disney’s 1950s fascination with Americana and identity through True Son (James MacArthur), a young man torn between his Indigenous roots and colonial assimilation. While it nods to racism, its simplistic portrayal of assimilation undermines a fuller respect for First Nations cultures.

The evolving frontier

As the Western genre waned in popularity, Disney adapted, reinventing it with humour and lighthearted charm to keep its appeal for family audiences.

In 1959, a very serious Leslie Nielsen took on Revolutionary War figure The Swamp Fox in multi-part Walt Disney Presents stories on TV, demonstrating Disney’s knack for creating Western-adjacent tales rooted in American folklore and history. You could even argue that Old Yeller (1957), with its post-Civil War setting, forms part of this continuum.

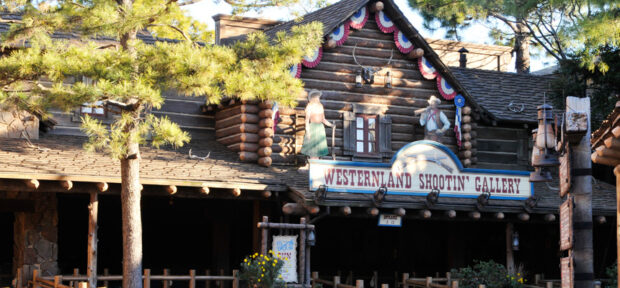

Perhaps the most tangible legacy of Disney’s Western era is found in the Frontierlands of Disney Parks around the world. The original in California, along with its sibling in Orlando, stands as a tribute to this cinematic era. In Paris, Thunder Mesa offers a unique backstory, created by the fictional Henry Ravenswood to support the mining town surrounding Big Thunder Mountain. Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s Grizzly Gulch takes inspiration from a Northern California mining town.

However, Tokyo Disneyland—almost 6,000 miles from the American frontier—might showcase the clearest tribute to this era. Their version, simply called Westernland, is a near mirror of the Magic Kingdom’s Frontierland, tipping its hat to Disney’s lasting vision of the Old West.

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot

All images in this article are owned by Disney unless stated otherwise.