Released in cinemas in 1950, Disney’s classic fairytale remains an enduring icon of the studio and its era, still casting its spell 75 years later.

If Disney today has the reputation of being a princess factory, this certainly wasn’t in the original plan.

By 1950, Disney hadn’t released a non-package animated feature film since Bambi (1942). The monumental success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was 23 years—and an animators’ strike and a world war—behind them. Millions of dollars in debt, the studio teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Could a return to fairy tales be the ticket to get Disney back on track?

We know now that it very much did. “If Snow White is the first lady of animation,” wrote the editors of a 2005 Special Edition ‘making of’ book, “Cinderella is surely the crown princess.” While every culture has a version of this tale, Walt’s inspiration was Charles Perrault’s 17th century story. It wasn’t the first time Disney had attempted this either, including the 1922 Laugh-O-Gram version through the various aborted attempts in the 1930s and 1940s.

By the bibbity-bobbidi-book

The work of 750 artists, 1,500 colours, and over one million drawings—all under the direction of Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Clyde Geronimi—CINDERELLA is an animated masterpiece in every sense of the word. What struck me on a recent rewatch was how compact the storytelling is. In only 74 minutes, we get the whole familiar story: the stepmother and stepsisters, the Prince, the Fairy Godmother, the Ball and the glass slipper. Serving as a counterpoint is the little war between the mice, Lucifer the cat and the other animals. It shouldn’t necessarily all work together, but part of the magic is that it just does.

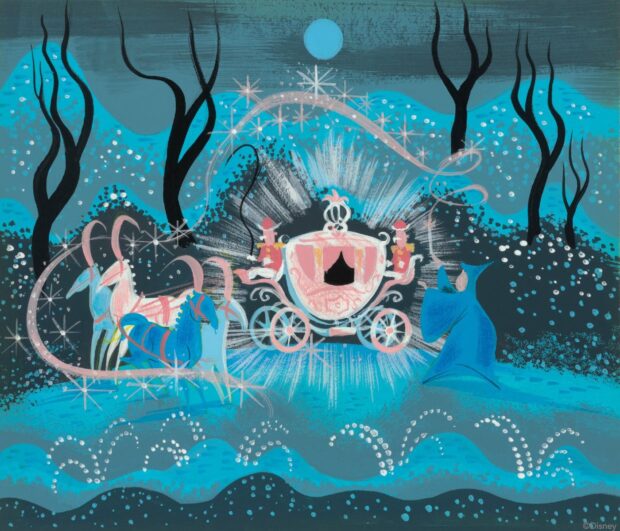

From the moment the film opens, the artistry is unmistakable. Marc Davis and Eric Larson’s naturalistic animation of Cinderella—based on live-action footage of Helene Stanley—stands in stark contrast to the exaggerated human caricatures of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), the film that immediately preceded it. It culminates in one of Walt Disney’s favorite pieces of animation: Marc Davis’ breathtaking sequence of Cinderella’s transformation into her ballgown, made even more magical by George Rowley’s individually animated sparkles. (The Ink and Paint department later had to painstakingly paint every single one of them, frame by frame).

Other highlights include Ward Kimball’s wildly expressive work on Lucifer, particularly during the ‘cup game’ sequences. Milt Kahl imbues the Fairy Godmother with warmth and charm, making her memorable despite only appearing in a handful of scenes. Frank Thomas crafts an absolute icon in the Evil Stepmother, conveying more menace through a single raised eyebrow or curled lip than some films manage in their entire runtimes. Meanwhile, Ollie Johnston’s broad caricatures of the stepsisters make them just as unforgettable.

If these approaches seem stylistically varied, it’s the ‘story first’ philosophy that ultimately unifies them. Take, for example, the ‘key’ sequence in the film’s climactic moments. Story animator Wolfgang Reitherman devised the idea: while the stepsisters attempt to try on the glass slipper downstairs, the mice desperately struggle to carry a key up the stairs—past the ever-menacing Lucifer—to free Cinderella. The tension is palpable. As legendary animator Andreas Deja later put it, “It’s like a Hitchcock film.”

Oh sing, sweet nightingale

Then there’s the music. For the first time, Disney turned to Tin Pan Alley—the legendary New York songwriting hub—for a major project. Mack David, Jerry Livingston, and Al Hoffman not only understood how to craft a “story song” that drove the narrative but also knew how to write hits.

The results are certified bangers. Apart from the main title, the film features just five songs, each a standout. A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes, the quintessential “I wish” number, almost instantly became a signature tune for the studio. The jaunty Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo, with its nonsense lyrics and lively animation, is simply iconic. So This Is Love closes the affair on a high note—a waltz practically designed for weddings.

In addition to earning an Oscar nomination for Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo, these songs were the first published under the newly formed Walt Disney Music Company. Cinderella went on to win the Golden Bear for Best Music Film at the inaugural Berlin International Film Festival in 1951, cementing its international reputation.

Restoration

In 2023, Disney released a 4K restoration of Cinderella—one of the key inspirations for my return to physical media. Restoration director Kevin Schaeffer, along with the legendary Eric Goldberg and others, not only brought out the fine details in the print—including the film’s phenomenal use of light and shadow—but also restored the original colours. As it turns out, we’ve been looking at the wrong ones for decades.

“Her hair [is] dusty blonde,” Goldberg told Polygon, “and her dress is silver. And over the years, we’ve seen her hair look the color of Cheez Whiz. We’ve seen her dress be bright blue. We’ve seen all sorts of stuff.”

This restoration wasn’t just about returning to the source material—it was about preserving the film as it was meant to be seen. The legendary Mary Blair, one of Walt’s favourite artists and designers, created extensive concept art for the film, her striking use of colour shaping its visual identity. Long muted by various home video transfers, her vibrant palette is now finally restored to its full glory, allowing modern audiences to experience the film as its creators intended.

Dreams really do come true

When CINDERELLA premiered in cinemas in 1950, it transformed the fortunes of the Walt Disney Company. A box office hit, it earned three Academy Award nominations—for its score, sound recording, and the song Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo. With his mojo back, Walt Disney forged ahead into new territory, expanding into television, live-action cinema, and the creation of Disneyland.

More immediately, it sparked an animated revival, paving the way for Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, and Sleeping Beauty—all released before the decade’s end. “Cinderella saved the day,” animator Frank Thomas once said. “We had our audience back and were back in the feature business.”

Through sequels and remakes, the original film’s legacy is literally built into the foundations of Disney history. Its castle, immortalized as the centrepiece of the Magic Kingdom, has been replicated around the world and now graces the studio’s ident at the start of every film.

Portions of this retrospective were adapted from an earlier review I wrote on Letterboxd. All images © Disney except where noted.