Have you ever eaten nattō? The Japanese fermented soybeans are, for want of a better phrase, an acquired taste for western palettes. The strong dark flavour and long sticky tendrils have turned their share of noses, but in the hands of Kōta Yoshida they might be one of the most erotic dishes on the planet.

In SEXUAL DRIVE, writer/director Yoshida presents a triptych of tales at the intersection of food and sex. It’s a film that feels both self-assured in its horniness, while also being excessively creepy and flirting with danger. Running through all three segments is the character of Kurita (Tateto Serizawa), who is kind of like a super randy and Faustian version of Leos Carax’s Monsieur Merde.

In the first of three stories, appropriately titled ‘Nattō,’ Eratsu sees his wife off to work. Shortly after, in walks Kurita, crippled from a stroke, toting a box of Chinese chestnuts under his good arm and a telling a tale of his sexual liaisons with the Eratsu’s wife. Without any explicit scenes, Kurita vividly describes their nattō related encounters. The story leaves the hitherto sexless Eratsu writing in emotional agony, but fully erect.

So, how reliable is Kurita as a narrator? It’s a question that follows us into ‘Mapo Tofu‘, the second chapter in this anthology. A woman with social anxiety drives to pick up the titular discount mapo tofu but apparently hits Kurita with her car. While driving him home, he talk to his own masochism for real mapo tofu that is “red like lava” and reveals the lead’s own sadistic past as his schoolyard bully. What he asks of her next evokes a violent and pseudo-sexual awakening, but we are still not sure how much to believe.

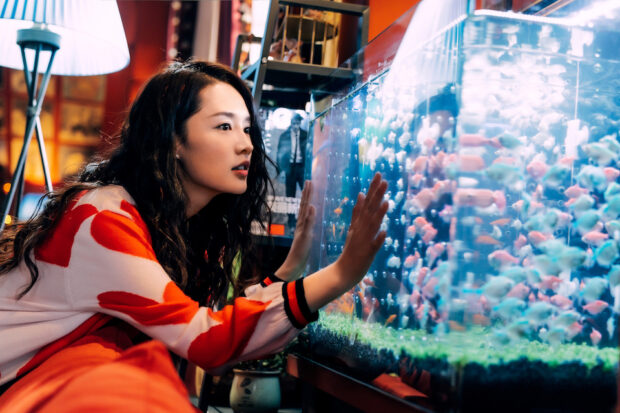

The last of the tales is arguably the most successful in its ambiguity. If you thought that Tampopo was the last word on ramen, then ‘Ramen with Extra Back Fat‘ might give it a run for its money. In a packed ramen bar where talking is forbidden, Kurita remains unseen but speaks to a man via his phone’s headset. He weaves an audio narrative of his girlfriend Momoko, and how her ramen desire spills out of the bowl and onto the men around her. As Kurita says, “It is truly violent.”

Yet for all its talk of unleashing the inner hedonist, the film is a slave to its format. Kurita’s insistent speeches are uncomfortable to watch at times, feeling for all the world like a verbal assault on the leads. Still, all three stories climax in imagery of passion so unbridled that it would be hard to top outside of pornography.

You will never see mapo tofu being cooked more intensely or orgasmically, and Yoshida’s regular cinematographer Masafumi Seki finds salacious new angles in the kitchen. The camera is often so close to the characters that you might just get splashed with ramen broth. Fans of ASMR will also dig this.

Perhaps the most unsettling thing about SEXUAL DRIVE are the number of unanswered questions. We never truly learn who or what drives the suggestively named Kurita, and we might imagine him out there somewhere whispering sticky somethings in a repressed diner’s ear. Or maybe we’ll just take the advice of Momoko and “just call it a night after ramen.”

2021 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Kōta Yoshida | WRITER: Kōta Yoshida | CAST: Serizawa Tateto, Hashimoto Manami, Ikeda Ryo, Sato Honami, Nakamura Mukau, Takeda Rina, Shogen | DISTRIBUTOR: SHAIKER, Fortissimo Films, International Film Festival Rotterdam | RUNNING TIME: 70 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 1-7 February 2021 (NL)

Read more coverage of Japanese cinema from the silent era to festivals and other contemporary releases. Plus go beyond Japan with more film from Asia in Focus.