The New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF) has come and gone for another year. As usual, we were not left disappointed by any stretch of the imagination.

NYAFF is a one-of-a-kind celebration of films from across Asia and the Asian American experience. Each year it showcases films from Japan, China, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, Taiwan, the USA and even Kazakhstan (Sweetie, You Wouldn’t Believe It).

Given the high profile of South Korean cinema right now, it’s no surprise that the festival opened and closed with two blockbuster Korean films: ESCAPE FROM MOGADISHU and SINKHOLE. From Hong Kong, the late great Benny Chan’s final film, RAGING FIRE, was given a glorious final bow in a year where LIMBO, TIME and HAND ROLLED CIGARETTE all reminded us of the glory days of HK cinema. Japan’s two major sequels — THE FABLE: THE KILLER WHO DOESN’T KILL and LAST OF THE WOLVES were amazing highlights as well.

So, here’s a deeper look at some of the terrific films we managed to catch at historic 20th edition of NYAFF this year. You can also see the rest of our coverage at our NYAFF 2021 festival hub.

We’d like to thank the NYAFF festival organisers for their generous access to films and materials — and we’re already making plans for a drink to celebrate your 21st birthday next year.

Escape from Mogadishu

The biggest South Korean release of the year is a top-notch action thriller set against not-too-distant history. In January 1991, amidst rising rebellion and the ultimate collapse of Somali President Barre’s government, the South and North Korean embassies find themselves working together to flee the country before the violence escalates further. The aftermath of this event, and broader Somali Civil War, has famously been depicted by Ridley Scott in Black Hawk Down (2001). Although playing out on a small scale, and with a drastically smaller budget, Ryoo skilfully manoeuvres the audience to a bittersweet ending via a breathless series of spectacularly staged action sequences. Read our full review.

Raging Fire

The film world lost Benny Chan last year after a short bout with cancer. His final film — starring Donnie Yen and Nicholas Tse — gets a posthumous release, and it’s as fitting a tribute as any to one of the true heroes of Hong Kong action filmmaking. As the film closes out with footage of Chan at work, coupled with a dedication to the late director, even the most hardened of HK action fans will probably feel a little emotional. This is a film that knows its audience. Read our full review.

The Fable: The Killer Who Doesn’t Kill

One of those rare instances where the sequel outdoes the original. A standalone sequel that doesn’t require knowledge of the first one, it scarcely mattered that it’s been a couple of years since I’d watched the predecessor and completely forgotten the ending. This time, all the pieces come together quite nicely, and there are at least two large scale set-pieces that are world class. Strong hints at a third outing, so hop aboard the Fable train now. Read our longer review.

Last of the Wolves

The follow-up to The Blood of Wolves, a film that never really got past its stylistic excess. Which is where this sequel tops it in every way. Yes, there’s still a fair bit of blood, but there’s also a wicked driving narrative in this clash of wills. Ryôhei Suzuki adds a dangerous element that genuinely keeps us guessing, and it all comes to a satisfying conclusion in the vein of Infernal Affairs or the Outrage series. Or leaves the door open for even more explorations of this old-school battle without honour or humanity. Read our even more exciting full review.

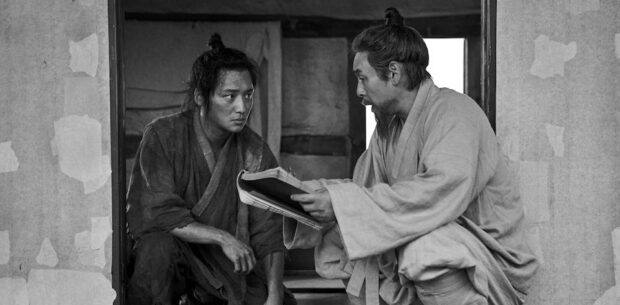

The Book of Fish

A remarkable and beautifully shot monochrome gem that is equal parts meditative and poetic. Two central performances carry this, but the supporting cast is charming and effective. While there are some specific cultural touchstones here, they are not really a barrier to entry. Read our full review.

The Silent Forest

A Taiwanese film about sexual abuse in a school for hearing impaired kids is exactly as emotionally harrowing as you’d imagine. The cast of excellent young actors, and a refusal to provide us with all the solutions, really makes this piece on the cyclical nature of abuse engaging and memorable. Read our complete review.

A Balance

An intriguingly multi-layered narrative, and arguably too multi-layered. Lots of strands that touch on some real and still unresolved issues in Japanese society (and beyond) – trial by media, sexual assault, abortion laws – but even in the slightly long running time they don’t get fully addressed. Part of me wants to recut that ending with the Curb Your Enthusiasm theme music. Read our full review.

Limbo

Cheang Soi’s Limbo is a throwback Category III Hong Kong thriller that may not always feel cohesive, but with the stark black and white photography, it’s never anything less than stylish. The action climax, in which our hero fights the killer in the rain, is a relentless showdown that should rightfully be praised as one of the greats. In fact, this goes for all of the action and set-pieces peppered throughout. Read our full review.

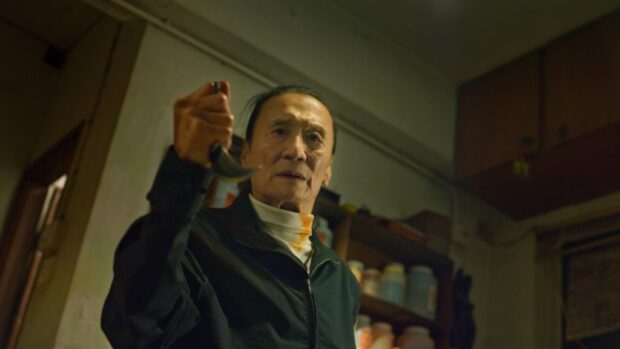

Time

This might be Ricky Ko’s debut feature, but in every other way it’s got the look and feel of a throwback to Hong Kong’s past cinema greats — not least of which is the 84-year-old former matinee idol Patrick Tse. He plays a killer for hire who now takes on euthanasia cases. Sometimes an odd blend of tones, but ultimately the core performances and the slick action carries this ‘grandpa assassin with a heart of gold’ through to the end. Read the full review.

Fighter

A solid character study about a North Korean refugee who finds an outlet through boxing. Yun Jéro’s film avoids some of this minefield of issues by focusing less on ideological differences and more on a general feeling of societal disconnection. Read our full review.

Sinkhole

This blockbuster film may begin with a light-hearted tone, but seamlessly transitions into a disaster movie that manages to keep the comedy coming as regularly as the dramatic twists. It’s already the fastest film to pass one million viewers in South Korea this year, marking it as late contender for one of the highest grossing Korean films of the year — so make sure you jump in and see this before the inevitable Hollywood remake. Read our full review.

Hand Rolled Cigarette

A slick debut continues the the revival of Hong Kong cinema in this beautifully shot thriller. Although ultimately losing the top prize to Taiwan’s My Missing Valentine, the seven nominations at the 57th Golden Horse Awards mark director Chan as a voice to watch. Read our full review.

Under the Open Sky

As a character study, this works incredibly well. Koji Yakusho once again finds himself on the wrong side of the law in this exploration of institutionalisation resulting from long-term imprisonment. He’s excellent in the role, bringing a world weariness and hair-trigger anger that never feels anything less than genuine. Some of the more plot-driven elements let it down in the back third – including a conclusion (that I won’t spoil here) that felt like one step too much – but it’s generally an admirable outing.

Blue

There’s something about NYAFF and boxing films (see also: One Second Champion) that keeps drawing me back in. This is a solid character piece thanks to the three charismatic leads, each damaged in their own way and looking to boxing for answers. What I particularly like is that despite some of the boxing movie tropes it falls back on, it refuses to offer any easy solutions by the end.

Tiong Bahru Social Club

First things first: the film is gorgeous visually. A fun skewering of the algorithmically dominated social media landscape played out IRL. The illusion of choice and the myth of happiness are explored in a lighthearted way, but like actual social media what really brings this all together is an adorable kitty.

Junk Head

Like the earlier editions that this builds upon, one has to salute Takahide Hori for the amazing effort that has gone into the stop-motion/CG blend here. With an aesthetic that sits at the exact intersection of Despicable Me and a Tool music video, the painstaking level of detail found in every frame of this film is nothing short of phenomenal. While the character designs and creature revelations are often ingeniously crafted, long stretches of the film are simply figures chasing each other around corridors. Read our full review.

One Second Champion

Follows the low-key adventures of a downtrodden dad gifted with the ability to see one second into the future. An interesting light wibbly time premise that, like the titular champion, never really finds a good use for the concept. When it does just become a straight boxing film, it works quite well – complete with its own handful of Rocky moments.

Midnight

In the grand tradition of Hush or Wait Until Dark, a woman with a hearing impairment becomes the target of a serial killer. That’s the premise of Kwon Oh-Seung’s debut film, one that draws inspiration from Korea’s own I Saw the Devil and through to overt references to The Shining. A sensory thriller with a solid cast will keep you on edge with a few clever tricks up its sleeve. Read our full review.

Ninja Girl

An odd little premise that never quite gets up off the ground, but like the titular character, quietly sneaks up behind you and works its way into your conscience. The chaotic ending is a barrel of fun as well, with the film living up to the title and giving our diminutive hero a minor victory. Read our full review.

As We Like It

A near-future spin on Shakespeare continues to play with gender roles, but gets a little lost in their exits and their entrances. Given Taiwan’s broader attitudes to LGBTQI+ issues have only recently progressed, AS WE LIKE IT may seem like a quantum leap. (Especially when compared with last year’s The Gangs, the Oscars and the Walking Dead). Yet as this chaotic, cheeky and often undergraduate collage of influences rolls into its statement denouement, one can’t help thinking what a bitter a thing it is to look into happiness through another man’s eyes. Read our full review.