Disney’s most experimental series gave us pigs, kittens, tortoises and hares. They not only won numerous awards, but they advanced animation as an art form.

Between 1929 and 1939, Disney released 75 musical short films. Unlike the Mickey Mouse, Donald, and Goofy cartoons of the same era, they were designed to be pure experiments in animation, storytelling and, most importantly, music.

In that decade, seven of the shorts won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. They transitioned from black and white to pioneering colour. They ultimately led to the development of the first full-length animated film.

They were the Silly Symphonies.

The symphonic spine of Disney

When the first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance, appeared in August 1929, audiences had been enjoying Mickey Mouse cartoons for almost a year. Mickey was at the peak of his success, and we were still a few years off Donald entering the picture. Based on a conversation with composer and old friend Carl Stalling, Walt got the idea of doing a series of short musical novelty cartoons.

Leonard Maltin once described this first film as one of his favourite Disney shorts, and it’s easy to see why. From the opening shot of an owl ominously getting caught in the wind, swiftly followed by two cats fighting on gravestones, this is the stuff that Halloween specials were made for.

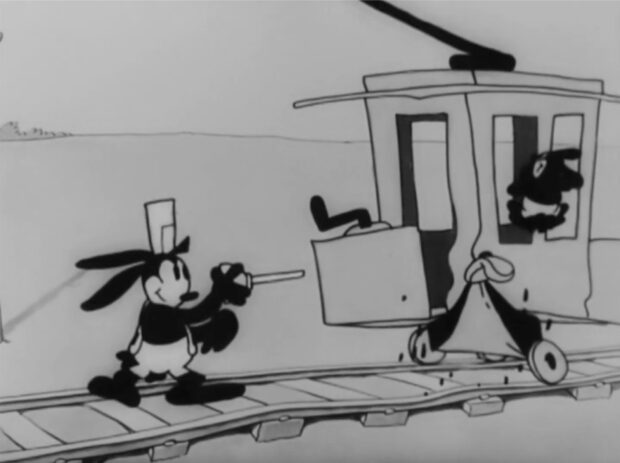

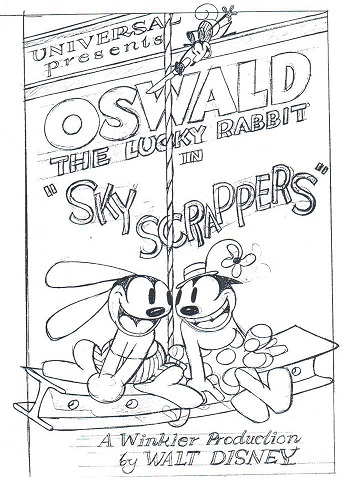

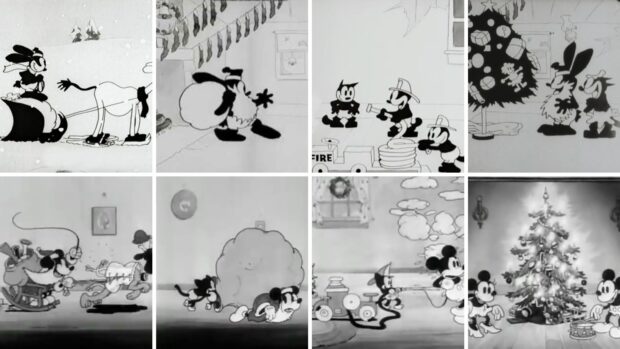

As the first of the Silly Symphonies, it’s great to see animators Ub Iwerks, Les Clark and Wilfred Jackson getting to cut loose on something other than Alice, Oswald or Mickey. From POV shots to the lithe movement of the skeleton figures, there is a noticeable upgrade to the technique here from the Mickey shorts. The synchronised sound has levelled up as well: animals caw, bark and crow, while the xylophone is perfectly timed as bones are struck. At the time, The Film Daily called it “one of the most novel cartoon subjects ever shown on a screen.” Still, to paraphrase a popular Al Jolson film of the era, they ain’t heard nothin’ yet.

Advancement through technology

If you ever want a quick lesson in how animation techniques advanced over the course of a decade, watch the Silly Symphonies.

The early shorts follow a formula. Hell’s Bells (1929) remixes and reworks Skeleton Dance, but this time in the underworld. A quartet of seasonal offerings – Springtime, Summer, Autumn and Winter (all 1930) – each play with critters creating syncopated sound as they tap and dance their way across nature. In fact, a contemporary review of Autumn in Motion Picture News perfectly described it as “Well done, but constructed along the same lines as most cartoons.”

In 1932, a mere decade after Disney’s first primitive attempts at commercial animation, the company introduced colour into their productions in Flowers and Trees. After watching Mickey Mouse’s star rise while the Silly Symphonies experienced diminishing returns, Walt turned to the new 3-strip Technicolor process. An advance on the more common 2-strip process, Walt traded off the expense for exclusive rights to the technique. Technicolor got a new ambassador in Disney, and the animation studio got a point of difference from their competitors. Every Silly Symphony from this point forward was in colour.

This is where they really start experimenting. In 1934, Goddess of Spring was playing with more realistic humans in anticipation of a feature. A retelling of the Hades and Persephone myth, Hamilton Luske’s animation on Persephone doesn’t quite hit the mark. Her rubbery arms and cartoonish leanings haven’t quite progressed as far as Disney would have liked. The studio animators would later study anatomy, advancing their craft by decades in a matter of three years for their first feature. Yet she is still a striking figure compared with the barnyard animals we’d seen so far.

Topping pigs with pigs

By late 1933, Disney had a legitimate phenomena on their hands with Three Little Pigs. Backed by a catchy song (‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?’), the first commercial success for a Disney record, it went on to win the Academy Award for Short Subjects, Animated Films in 1932/1933, beating out Disney’s own Mickey Mouse short, Building a Building.

Yet it’s the expressive animation and storytelling that sets this short apart, a result of the development of a dedicated story department at Disney. This meant that this short was less about gags and more about a complete story experience. All the little details are terrific as well, not least of which is the framed photo of the Pigs’ father — as sausage links.

The massive success of the short brought Disney to a crossroads. When contemplating the folly of trying to repeat the achievement, Walt would famously quip that “You can’t top pigs with pigs.” The key to success, he often said, was in perpetually looking forward.

Which the animators did for the most part, but Walt’s penchant for spending money (and his brother Roy’s attempts to rein him in) meant the occasional sequel. Three Orphan Kittens (1935) was followed by More Kittens (1936). The Tortoise and the Hare (1935) saw a rematch in Toby Tortoise Returns (1936). The pigs came back no less than four times, and continued to cameo during the war.

The road to features

By the late 1930s, the days of Silly Symphonies were becoming very costly to produce, especially as the techniques grew more complex. In December 1929, Walt told the New York Daily News that “It costs about $7,000 to make a Silly Symphony.” Less than ten years later, Mother Goose Goes Hollywood (1938), featuring caricatures of Hollywood celebrities in a storybook setting, was reported to cost $69,307.87.

Yet every single short was about advancing the technique. We watched directors like the technically minded David Hand, the always reliable Ben Sharpsteen, and the multitalented Wilfred Jackson hone their storytelling. Composers Frank Churchill and Leigh Harline became go-to musicians for relating a tale through melody. Even though Ub Iwerks and Carl Stalling had left the studio, a new generation of animators got to show their stuff, including Les Clark, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Frank Thomas and Ward Kimball. Each film was one step closer to the tools needed to make the feature that would become Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937.

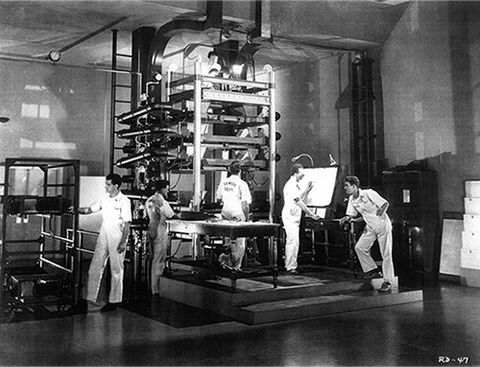

To illustrate this shift, look at three key shorts from the late 1930s, two of them before and one after Snow White – The Old Mill (1937), Wynken, Blynken and Nod (1938), and The Ugly Duckling (1939). The Old Mill marks the first use of the multiplane camera, one that allowed the calculated moving and layering of panels in a parallax process that created the illusion of depth. You can see this immediately as the camera pushes past a spiderweb in the foreground.

Adapted from Eugene Field’s verse, and with Leigh Harline writing the accompanying music, Wynken, Blynken and Nod is a whole little musical told completely in 8 minutes. The animation feels a decade ahead of its time. In 1984, Leonard Maltin wrote that it is “as extravagant as any Disney feature; it set a standard that was probably too extravagant to maintain.”

The decade, and indeed the Silly Symphonies itself, began to close out with The Ugly Duckling, a short which brought the series full circle. Although this is a remake of 1931 black and white Silly Symphony of the same name, from the moment we see a ‘father’ duck pacing expectantly, we can see that Disney are now in the business of making animated characters rather than simply the illusion of movement.

Also separating this short thematically from its predecessor is how the two otherwise similar stories resolve themselves. In the 1931 version, the titular character must prove itself useful to the others. Here, the duckling/gosling just has to find their people and be accepted by them. It’s almost the antithesis of the standalone short Ferdinand the Bull (1938), a coded queer narrative where the lead always had parental acceptance.

A silly legacy

At the time of writing, only 18 of the original 75 Silly Symphony shorts are on the Disney+ flagship streaming service. Indeed, only this month Skeleton Dance was added to the platform. While some remain Vaulted due to their insensitivities towards gender and race, others are genuine tentpoles in the history of animation.

By the end of the 1950s, Disney was concentrating solely on features, live action, theme parks, and television. Walt’s quest for perfection through experimentation found a new outlet in Disneyland rides and audio animatronics. Yet the very building blocks of modern animation are here, and it’s no fluke that competitors rushed to label their films Merrie Melodies, Looney Tunes and Happy Harmonies.

Yet while the series of films stopped, the pushing of boundaries didn’t. In 1940, Disney released the groundbreaking Fantasia, a concert feature marrying sound and vision in the wildest ways. Package features like Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948) followed suit. In 1999, the animated series Mickey Mouse Works revived the Silly Symphony moniker for a short-lived series.

The legacy of the Silly Symphonies is the existence of animation as a modern commerical art form. There are nods to them in the Cuphead video game series and, of course, The Simpsons. Their DNA is in the many moving parts of Pixar’s Elemental and the watercolour/CG styles of the upcoming Disney film, Wish. It’s in the online SparkShorts program and the Short Circuit series. So, here’s hoping that one day Disney presents all of the Silly Symphonies on Disney+ for historians and animation fans alike.

MORE FROM DISNEY MINUS: Newman Laugh-O-Grams | Walt’s first fairy tales | Alice Comedies | Oswald the (Un)lucky Rabbit | Silly Symphonies | The Spirit of 1943 | So Dear to My Heart | One Hour in Wonderland | The early lost films | Johnny Tremain | Westerns of the 1950s | Moon Pilot

All images in this article are owned by Disney unless stated otherwise.

![Review: Gold Kingdom and Water Kingdom [Nippon Connection 2023]](https://thereelbits.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/gold-water-kingdom001f-203x150.jpeg)