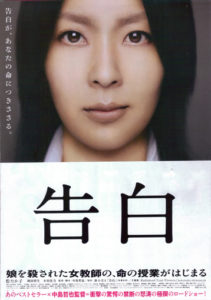

There has been a fair amount of hype surrounding Confessions (告白), the latest film from Memories of Matsuko and Happy-Go-Lucky writer/director Tetsuya Nakashima. When it was released in Japan earlier this year, it spent a whopping four weeks at the top spot (although was admittedly knocked off by the unfortunately titled Bayside Shakedown 3: Set the Guys Loose). Along with being based on the 2008 best-selling Japanese novel by Kanae Minato, which according to AsianMediaWiki has sold over 700,000 copies to date, it is Japan’s official entry for the best foreign-language film category at the Academy Awards. Is it even possible to watch a film like this without any baggage? The answer is unequivocally “yes” when the film is this good.

On an average day at a middle-school, teacher Yoko Moriguchi (Takako Matsu, Villon’s Wife and Brave Story) calmly tells her class about the tragic death of her four-year-old daughter at the hands of two of their classmates. The initial shock and slight disbelief turns to horror when she further announces that she has tainted the two killer’s cartons of milk with HIV-infected blood. As we learn more about the story, each of the characters confesses their sins to the audience and new clues are revealed to this tragic tale. Yet as the lives of the two boys slowly start to unravel, we find that Moriguchi’s plan is a complex one indeed.

Dealing with difficult issues from school bullying, teenage violence and mental anxiety to murder and the prejudice over HIV/AIDS in the school system, Confessions is also a tightly woven thriller that barely lets you take a breath. Although drawing on some of the same themes as Sion Sono’s brilliant four-hour epic Love Exposure, the comparisons should end there. Where Sono’s film used the language of pop-culture to almost hit you over the head with the out-of-control influence on youth, sex and religion, Nakashima goes straight for the jugular in a coldly calculated way. Shot with almost slate-blue and grey tones, and accompanied by a theme song (“Last Flowers”) provided by Radiohead, Confessions slowly unfolds its grand plan to audiences, yet could never be accused of being tedious. Even at its most violent, Nakashima and cinematographers Masakazu Ato and Atsushi Ozawa infuse every scene with a surreal beauty that captivates as much as it horrifies.

As violent as some of the acts in the film are, the real terror comes from the human drama. Each of the main characters is given their own segment, or ‘confession’, giving us insight into the motivations of each player. If any criticism could be leveled at Confessions, it is that we don’t get enough time to spend with each of these characters. Takako Matsu’s performance is less of a role and more of a presence, one felt all throughout the film, despite that she is only really on-screen in a handful of scenes. We can almost feel her hands silently manipulating events behind the scenes, something that would only become more palpable on repeat viewings. Each of the kids is also excellent, tackling weighty tasks such as self-harm, torture and outright cruelty with a frightening reality. Did these actors have to draw upon some external source of motivation, or are these feelings inherent to us all? Do these cold-blooded killers deserve special treatment because they are so young, or is murder simply murder? The often terrifying portrayals by these youngsters may leave you questioning your own beliefs, especially when one finds themselves silently cheering at Moriguchi’s final revenge.

While this may not wash with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences at the next Oscar night, it has received the attention of a number of international festivals including the Jury Prize at the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival in South Korean. It deserves to be spoken on in the same breath as Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, and equally twisty tale of revenge and taboo themes. Although dealing with incredibly familiar themes of murder, revenge and guilt, this thriller manages to present them all in an original way that keeps you guessing until the end. Brutal and often confronting, Confessions is a film that is impossible to ignore.

Confessions is playing at the 14th Japanese Film Festival nationally. It is due to play again at Melbourne on 4 December 2010.