With this year’s Shoplifters, filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda finally saw one of his films win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes International Film Festival. It’s staggering when one considers a career that stretched back to 1991, and has included some of the most critically acclaimed films of that time. Not for nothing, Kore-eda is regularly compared with Yasujirō Ozu in his approach to Japanese family interactions.

First released on 28 June 2008, STILL WALKING (歩いても 歩いても) remains one of Kore-eda’s finest examples of the inter-generational tension that exists between traditional and contemporary Japan. As Trevor Johnson, writing for Sight & Sound in 2010, puts it: “however one positions Still Walking in the firmament of Japan’s cinematic achievements, one thing is sure: it belongs up there with the masters.”

Kore-eda’s setup is deceptive simplicity itself. The Yokoyama family gather annually to commemorate the death of Junpei, who died 15 years earlier saving the life of another boy. His father Kyohei (veteran actor Yoshio Harada) is a retired doctor. Junpei was always meant to take over the practice, and estranged son Ryota’s (Hiroshi Abe) career in art restoration was a disappointment. Kyohei and his mother Toshiko (Kirin Kiki) also lament Ryota marrying a widow with a young son. Over the course of a lazy summer day and night, the family – which also includes daughter Chinami (You) and her husband and children – share memories both painful and joyous, scraping the surface of an underlying tension that seems impossible to resolve.

At the time of release, Kore-eda had already developed a reputation in directing documentaries and features. Making his directorial debut 1991 with the television documentary, Lessons from a Calf. His first feature, Maborosi (1995), earned him Best Director at Venice Film Festival, and he continued to develop a reputation internationally exploring death in After Life (1998), cults and suicide in Distance (2001), and revenge in the period piece Hana (2006). Arguably Nobody Knows (2004), about a 12 year old boy forced to care for his siblings in a small Tokyo apartment, garnered him his biggest recognition to that point.

From the opening shots, STILL WALKING solidifies Kore-eda’s aesthetic as a filmmaker. He and regular cinematographer Yutaka Yamasaki anchor the narrative immediately around the Yokoyama family kitchen. Establishing the tone through a conversation between Toshiko and Chinami about the relative value of root vegetables, the motif is serves two purposes. Eating is always evocative of memory, and repeated close ups of food and its preparation are a visual shorthand for nostalgia. Yet the conversation, and others just like it, let us know that the Yokoyama family has learned to keep most of their dialogue at the surface level.

These frequent moments and techniques have led many commentators (including this one) to compare the director to Ozu. STILL WALKING visually recalls the collaboration between the Japanese master and his cinematographer Yuharu Atsuta. Ozu was known for setting everyone in place, locking down the camera at low angles, and shooting. While Kore-eda isn’t quite this strict, there are long scenes taken from a single unmoving perspective. He’s also fond of what critic Noël Burch called ‘pillow shots’ in relation to Ozu: or “short place-setting moments between scenes.” Much of Kore-eda’s film feels like it would be happy to stay forever in these “pillow” moments. As the title would imply, leisurely strolls along the main road occupy much of the space between conversations.

Kore-eda has always maintained that he is more like Ken Loach, and perhaps that is because he intensely examines everyday character studies with a documentarian’s eye. When Ryota first arrives back home, he is physically too large for the space. Having literally outgrown his childhood, he rejects all the items from the past that his mother insists on keeping. As an audience, we feel that it is only a matter of time before his ticking bomb presence breaks the family.

Yet this is where Kore-eda’s nous for familial interactions comes to the fore. That subtext almost uniformly stays under the radar. Even with the annual arrival of the (now adult) boy that Junpei saved, the Yokoyama clan remains deferential to his clear lack of success, obesity, and general “no-hoperism.” Kyohei is less diplomatic, calling him a “useless piece of trash” after he leaves. We later learn that Toshiko secretly relishes making him feel awful because “not having someone to hate makes it all the worse for me.” Ryota labels this cruel, but she has a point.

The closest we get to any resolution comes in two key scenes. Following the departure of Junpei’s rescuee, Ryota haphazardly argues “Who knows how Junpei would have turned out. We’re only human.” The room stops cold for a moment, but nothing more is said. Ryota has burst some sacred bubble, and it will never be mentioned again. The film’s coda reflects on all the things unsaid, as we learn both Kyohei and Toshiko died off-screen before Ryota was able to do any of the things they’d planned for “next time.”

Kore-eda’s films in the decade since STILL WALKING have refined his technique further. We see it in the unabashed optimism of I Wish (2011) or the intense nature versus nurture of Like Father, Like Son (2013). Kirin and her “son”Abe were reunited in Kore-eda’s remarkable After the Storm (2015). Each of these films has continued to explore family in a different way, and with Shoplifters he once again shows his mastery of demonstrating the subtle way in which humans do human things. So perhaps by the time the 20th anniversary rolls around, we’ll no longer be comparing Kore-eda to other directors, with his impressive body of work marking him as one of the quintessential filmmakers of the 21st century.

STILL WALKING will have a special 10th anniversary screening at JAPAN CUTS 2018 with festival guest Kirin Kiki.

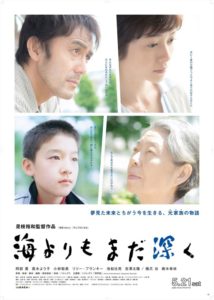

![]() 2008 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Hirokazu Kore-eda | WRITERS: Hirokazu Kore-eda | CAST: Hiroshi Abe, Yui Natsukawa, You, Kirin Kiki, Yoshio Harada | DISTRIBUTOR: IFC Films | RUNNING TIME: 114 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 28 June 2008 (Original release)

2008 | Japan | DIRECTOR: Hirokazu Kore-eda | WRITERS: Hirokazu Kore-eda | CAST: Hiroshi Abe, Yui Natsukawa, You, Kirin Kiki, Yoshio Harada | DISTRIBUTOR: IFC Films | RUNNING TIME: 114 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 28 June 2008 (Original release)