As we travel around Europe, we have found a number of cool things in Paris. The undoubted film mecca for lovers of early cinema is La Cinémathèque Française, one of the largest archives of film materials in the world.

Martin Scorsese’s Academy Award-winning Hugo highlighted the importance of film preservation for future generations, so it is appropriate that upon entering the main gallery space at La Cinémathèque Française, the Automaton featured in the film (pictured right) can be found wordlessly staring back at visitors to this stunning collection. From original pieces to recreations, La Cinémathèque Française is also a celebration of cinema’s history, housed in a stunning Frank Gehry building, appropriately located in the country that arguably gave birth to the medium.

Martin Scorsese’s Academy Award-winning Hugo highlighted the importance of film preservation for future generations, so it is appropriate that upon entering the main gallery space at La Cinémathèque Française, the Automaton featured in the film (pictured right) can be found wordlessly staring back at visitors to this stunning collection. From original pieces to recreations, La Cinémathèque Française is also a celebration of cinema’s history, housed in a stunning Frank Gehry building, appropriately located in the country that arguably gave birth to the medium.

In the first room of the gallery, a collection of relics and historical oddities can be found. There are, of course, the instruments of making moving magic, dating back to at least 1833. From this period we have a phenakistoscope, an early device that used the persistence of vision principle to create the optical illusion of movement. There are vintage cameras, zoetropes and a procession of vintage clips and films from the earliest days of cinema. Some of these were brand new to us, and represent just a fraction of the Cinémathèque’s collection.

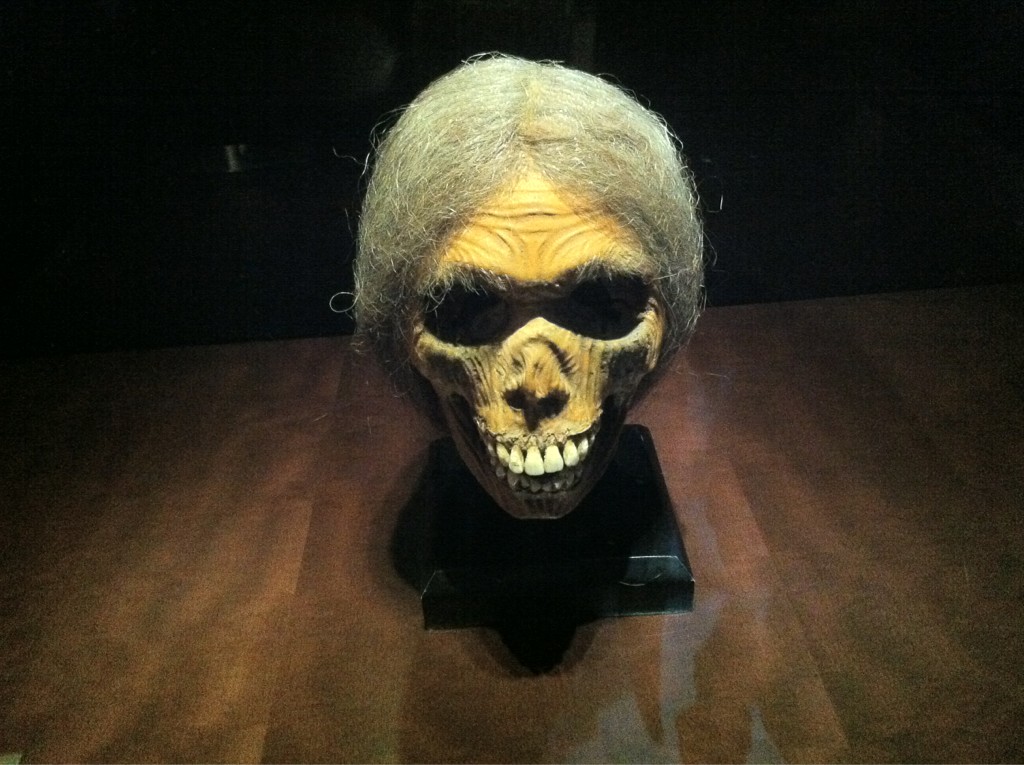

Whether playing to the popularity of Hugo, or simply there for the discovery, a number of pieces are dedicated to French cinema pioneer George Méliès, best known for Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902). There are original sketches from his films, along with recreations of some of the magnificent creature costumes used in the productions. A scale model shows the innovation of Méliès’ studio, with glass walls and ceilings designed to let in as much light as possible. The striped box seen in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) is on display, along with a number of costumes from the avante-garde section of the first floor. Perhaps the strangest piece to come across was Mrs. Bates head from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

Heading upstairs, the collection continues its focus on mythical objects, scenography and posters galore. With original issues of Cahiers du Cinéma, more artwork from films and information on various members of the organisation. When we arrived, a magnificent floor to ceiling landscape poster of Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (1946) greeted us, something we immediately decided was not possible to smuggle out under our shirts or through customs. You’ll be straight down to the well-stocked gift shop, featuring a selection of French and English-language books on cinema, along with a number of DVD and Blu-ray that are hard to find outside the country.

The Cinémathèque Française holds a number of film-themed exhibits too, of course, with a Tim Burton retrospective (last seen in Melbourne’s ACMI) on display during our visit. This, the gallery space and the spacious library are but the public face of the Cinémathèque Française, which actually holds one of the largest archives of films, movie documents and film-related objects in the world. The Bibliothèque du Film, created in 1992 to show the strength of the history of film, recently merged with the Cinémathèque.

If you are a fan of cinema and in the city of Paris, then this is a must visit location. After that, hop on a Metro and head down to the Left Bank, not too far from the Notre Dame Cathedral, and check out the plethora of geek and movie shops to be found, or just poke about in Shakespeare & Co. bookshop for some English-language books on a number of topics. Not too far away near the Sorbonne, sort of in the Latin Quarter, you’ll also find a string of cinemas in the Rue des Ecoles such as Cinema La Champo, La Filmothèque Quarter Latin and Grand Action. Between them, you could view things like Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983) or a homage to Claude Miller, a French filmmaker who began his career in the 1960s and passed away earlier this month.

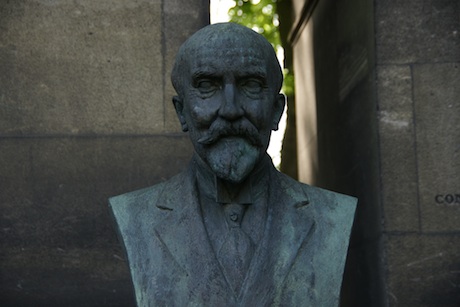

For a real pilgrimage, head out to see the final resting place of Georges Méliès at Père Lachaise Cemetery. Film fans have left notes of “thanks” to the pioneer, and the same cemetery also houses the graves of a number of famous creators, including Jim Morrison of The Doors, a well-kissed grave for Oscar Wilde and French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac. This is just of the tip of the iceberg: Paris is a city of film and culture, like no other on Earth.