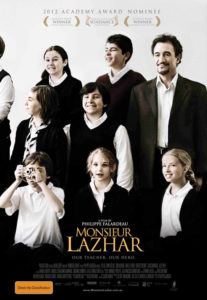

We spoke to director Philippe Falardeau shortly after his arrival in Australia for the Sydney Film Festival in June, where he happily admitted to still be fighting off the “evil jet lag” following a flight from his home in Montreal via Los Angeles. Falardeau’s Monsieur Lazhar was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 84th Academy Awards, only losing out to the unstoppable goliath of A Separation. It has also picked up 6 Canadian ‘Academy Awards’ (or Genies).

We spoke to director Philippe Falardeau shortly after his arrival in Australia for the Sydney Film Festival in June, where he happily admitted to still be fighting off the “evil jet lag” following a flight from his home in Montreal via Los Angeles. Falardeau’s Monsieur Lazhar was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 84th Academy Awards, only losing out to the unstoppable goliath of A Separation. It has also picked up 6 Canadian ‘Academy Awards’ (or Genies).

Following the suicide of a much-loved teacher, who hanged herself in her own empty classroom, a class of fourth graders struggles to come to terms with the tragedy. Bashir Lazhar (Mohamed Saïd Fellag), an Algerian refugee, is quickly hired to replace her, but he too is battling his own demons. Despite his cultural differences, and a grief that nobody at the school is willing to talk about, Lazhar begins to reach the class with his idiosyncratic style of teaching. In particular, Alice (Sophie Nélisse) earnestly tries to please to overcome her sadness, and Simon (Émilien Néron) – who discovered the body – continues aggressively acting out.

We need to thank Palace Films, who are distributing the film around Australia on 6 September 2012, and of course, Mr. Falardeau for his generous time and answers. [This interview contains minor spoilers for the film].

This is an adaptation, and you’ve worked with adaptations before, but what was it about the source material that attracted you?

Well, the key thing is that the night I saw the play, I was not scouting for a subject. For me, it’s always a relief when the subject finds me, and not the other way around. The fact that it was a solo play kind of helped in a way, because I started imagining the other characters around the main character of Monsieur Lazhar, who was just there on stage talking to people that we didn’t see or hear. Just imagining their responses and who they were. I guess you could say that in a way I was drafting the first script for my film, but what really got to me was his humanity, his dignity, his fragility also. I had been looking for a topic, a character that was an immigrant for years, but every time I had an idea it was too in your face, too didactic. This time, I had a real person in front of me, and it was not about immigration, although immigration was part of the issue. So I just turned to my producer, who happened to be sitting next to me that particular night to see the play, and said ‘Alright, we’re doing this’. He smiled and said ‘We’re doing what?’ [Laughs] I said we’re turning this into a film, and he was sceptical at first, but after my first synopsis he embarked with me and so here we are.

It sounds like you took your own direction, so how closely did you work with the playwright in developing the script?

It was important to me that she be my first reader, and I didn’t want to go astray with the main character. I didn’t want to turn him into something that was not in her mind. So I wanted her to be the guardian of her own character, but it was agreed from the start that I would be scriptwriting. She didn’t want to participate in the screenwriting, but it turned out that she gave me a lot of ideas when I painted myself in the corner sometimes. We would bounce back ideas, then I would go home and I would have a flash. She was really instrumental in my work, although I wrote alone.

When you were looking for your leading man, did you have someone in mind from the start, or was that a long process?

I had a few people in mind who are French from Algerian descent that work in France, because of the relationship that France and Algeria had, there’s obviously more Algerians in France than back home in Montreal. I saw a couple of actors in Montreal, but I knew that it wouldn’t do. So I had a few people in mind, and I made some auditions and some other people weren’t available for the auditions. In the meantime, someone told me to check out this guy [Mohamed Fellag] on YouTube. What he does is very different from Monsieur Lazhar. He’s a comic, he’s a stand-up comic, he writes monologues. His type of humour is really old, burlesque, candid humour with a sub-political text. It’s quite funny actually when you know the context, and very far from what I had in mind. But I liked his face, and I liked the fact that he also went through what Monsieur Lazhar went through, because he had to flee his own country back in 1992. So we met in Belgium where he was doing a show. With a lot of work, especially on his part, he was able to use a lot of restraint to achieve what he did in the film.

You say that the humour was far from what you had in mind, but there is a lot of humour in the film, which is interesting given the subject matter. Was it important for you to have someone with that sense of humour in there?

Yes and no, because I was precognisant that it was going to be the situation, and the way that I crafted the scenes in the film would make the humour pop-up. You often laugh in the film, but there’s no jokes. Apart maybe from that scene where the big guy wants an extra point and gets a dictionary also. That was really a joke on my part. Apart from that, we smile a lot, but the person didn’t have to have a comic background to do it.

The classroom itself feels very organic, and the classroom is a very complex beast in itself. How did you capture that? Did you have to go and look at modern classrooms for example?

Yeah, I think that’s a nice part of my job [Laughs]. When I find a subject, you have all kinds of reasons to do some research. I just phoned some teachers and asked them if I could spend some time in the classroom, and I was sitting in the back of the classroom taking notes on how the school worked nowadays, because the last time I was in an elementary school had been more than thirty-two, thirty-three years. It was just odd observing the children move on their chair, the children talk, the children drawing stuff, passing notes and stuff that you would not necessarily be able to write on your own. You capture some ideas, and you want the film to feel as organic as the class. The classroom is a place where a lot of young humans move all the time. There’s always someone dropping a pen, or moving or hitting someone. So with my assistant on the set, I made sure that everyone had something to do every time, that they would not just sit being idle doing nothing.

This of course leads me to asking about working with children. This is obviously not the first time you’ve done this. How do you have to adapt your style to work with them, or is it the other way around?

It’s a mixture of both. I try to install a playful atmosphere on set. Often when you’re shooting, it can be a military organisation. There’s a strong hierarchy, you give out directions and orders are brought down. With children you have to make sure that it’s more playful, so they don’t tire as easily, and you take more breaks. Also, before that I make sure I take a lot of time during the audition process, and not just see them for five minutes. Not one take and that’s it. You want to make sure they’re there for the right reasons. It’s funny, because when you’re auditioning a kid, you’re also auditioning the parents. So you want to make sure the kid is there not because their parents want them to become a movie star. So it’s a combination of a lot of things, but at that age what I found out was they do understand the psychology of the character. You don’t have to say do that faster or slower, you can talk about what’s happening in the mind of the character. They have an opinion on that, and they use different words, but they can understand the concepts.

Speaking of that understanding, this is very heavy subject matter, especially where the film starts. Did you have to explain those concepts to the children, or was it more about them reacting to a scenario?

Well, it’s a long process, so they have time to see it coming. I often get that question in Q & As, from people who just saw the film, who just experienced the drama in real-time with the characters. The children who played the characters go through a really long process 3 to 4 months before the shooting starts, so they can discuss it with me, the parents and their friends. There is a moment, a very important one, where we read the script and we stop at every scene, and we talk about what’s happening in the scene. The education of the parents is paramount here. Eventually, a huge responsibility lies on their shoulders to decide if they want their children to be in that film. But certainly I was always, always at any moment open to discuss what was happening. For instance, the scene where he discovers the body hanging, I made sure he met the stunt woman. ‘This is Suzanne, she’s flesh and blood. As you can see she’s doing well. She’s going to be hanging with this harness, this is how it’s going to work’. Then when it was hanging, I showed him what it looked like, because it could be very striking to see that body handing motionless. I’m not a big partisan of trying to scare or shock the actors on stage, it’s not a documentary it’s fiction, they can act.

Touching on that, one of the things the film is about are those structures between children and adults. Not only a very structured place, but one with very definite rules guarding the relationships between adults and children. Do you feel personally that there’s too many institutional barriers between adults and children?

In researching the film, that was a surprise to me. How many rules and regulations and protocols there are. I know why we’ve come to that, sometimes for very good reasons, but the theory is that no matter how careful we are, we will never be able to predict and prevent all bad situations. Let’s take for example the topic of child molesting, which is always a big paranoia thing in North America. Not matter what you do, things will happen. Bad stuff will happen. So now we have a decision to make. Do we want to dehumanise the relationship between the children and the adults to the point where nobody can touch anyone just to prevent that maybe someday something will happen? Or do we just let life take its course between normal human beings. I still say that we have to be vigilant, but go back to a situation where people can encourage children with a gentle tap on the back or hugging. Hugging, certainly, if a child is crying! On the first day of shooting, it’s funny Vincent Millard – you know the kid who plays the chubby kid, the blonde chubby kid – after the first day, he came and hugged me so hard. I was looking left and right, looking at people to say ‘I’m not touching him, he’s touching me’. I was totally paranoid, it’s completely ridiculous.

I’m obviously not the first to say this, but the two lead child actors are brilliant. Where did you find them? Looking at my notes, they both largely did commercial work, so what qualities were you looking for?

That’s a nice way to ask the question. “What qualities?” With her [Sophie Nélisse], what I liked was her eyes and her baby face. She has the eyes of an adult or an old soul, and a baby face, and the contrast was quite striking. I needed eyes like that because her character is very mature and precocious. Him [Émilien Néron] I needed someone that was more nervous, edgy, more erratic. He had that quality, but he tended to overplay sometimes. I tended to hear the text, so we worked a lot…but he does have the most amazing performance in the cathartic scene where his guilt comes out. I think it’s a situation where the environment has to be readied, and we have to be ready, and he has to dig inside to give us that moment. He trusted us. I wish I could say I had a special gift, or a special trick to make children act like that, but its a situation where you have a real life moment and I was there to catch it.

One of the things I’m also interested in is how much of you is in the script. There’s a certain nostalgic element, so how much of your own experience of being in school, for example, is in that film?

I would say that all children are composites of who I was. I’m a little bit of Alice or Simon at the same time, or Marie-Férdérique [Marie-Ève Beauregard] because I used to be the one who would say to the teacher that he couldn’t do this or that. I was a pain sometimes. I was a little bit anaemic like Boris [Louis-David Leblanc]. So I was all of them at the same time. But often also I dug into my own memories to find some really concrete solutions to some problems. For instance, I needed the young boy to find the body before everyone else. So while I’m writing, I’m thinking why is he in class before everybody else? The milk. Then I thought, I used to carry the milk before the class started. So I used that for a very specific reason, and it turned out dramatically to be very interesting, because at the end, he says that ‘she knew I was going to see her like that because she knew it was my day to take the milk in’. So I would say that I took a lot of things from my own childhood thematically, at least to try and seed the script.

One last thing I wanted to ask is, obviously the touring process has been going on for some time and you are now here in Australia, but have you had time to think about what projects you’ve got coming up next?

Yes. I was writing a script before this all started. I had a first version, my producer liked it. It’s always a long process of re-writing the scripts. Normally I write my ninth or tenth version, and I’m only at my first draft, so I need to get back at it. I haven’t had too much chance lately. But also, I’ve been getting some scripts from the United States, and if I am to do a film in English not written for me, I want to make sure it makes sense. I have no – my objective is not to go to Hollywood. If a film is presented to me, and I think I can do a good job with it, and it has something to say, and it is not just a studio film, but it has a social or political balance, I would certainly do it. It’s a long process to write and direct your own film. I’ve done four in 12 years, so its 3 years process every time. I think I’m ready in my life now to direct a film I haven’t written.