“The Man in Black fled across the desert, and the Gunslinger followed.“

In October 1978, those words kicked off “The Gunslinger,” a short story published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction by the relatively new writer Stephen King. Together with four other short stories on Roland of Gilead, the titular last Gunslinger, it was eventually collected as The Gunslinger, what would become the first of eight novels and numerous tie-ins that formed King’s keystone series.

THE DARK TOWER is no ordinary series. For King, it is The Series: capital T and capital S. In the afterword to Wizard and Glass, the fourth book in the main series of Dark Tower books, King writes:

“Roland’s story is my Jupiter – a planet that dwarfs all the others . . . a place of strange atmosphere, crazy landscape, and savage gravitational pull. Dwarfs the others, did I say? I think there’s more to it than that, actually. I am coming to understand that Roland’s world (or worlds) actually contains all the others of my making.”

As Constant Readers would find, THE DARK TOWER left its finger prints all over King’s other books – or was it the other way around?

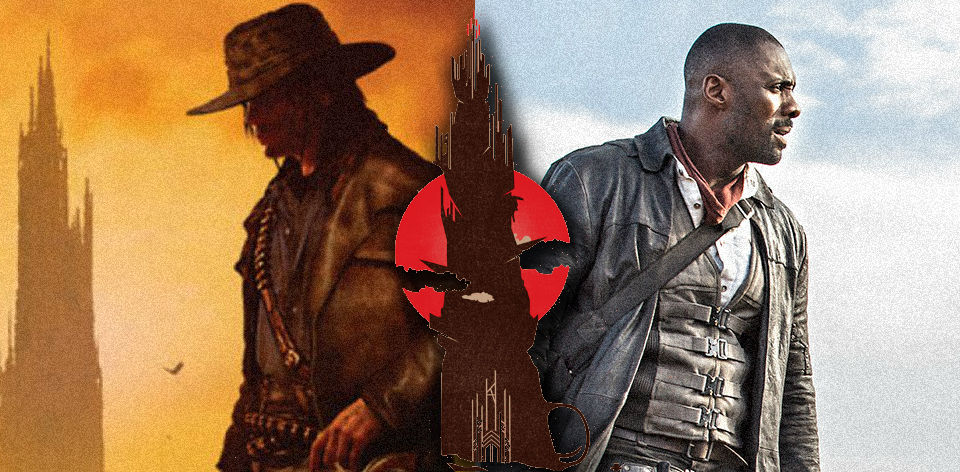

With the film coming out in August, rumoured to be both a remake and a sequel to King’s magnum opus, we palaver about the series that spawned it in context, including its intertextual connections to other media. WARNING: There will be spoilers for the book series. The choice is entirely up to you, dear Reader.

The story so far

King’s series is set in a world that has similarities to our own, but has “moved on” in key ways. A figurative and literal wasteland in parts, it’s a strange cross between the Old American West and a magical feudal landscape. Roland Deschain is the last descendant of the line of Arthur Eld, his world’s equivalent of King Arthur. He quests for the Dark Tower, a physical and metaphorical representation of the nexus of old worlds.

Joining him are the adolescent Jake Chambers, the reforming junkie Eddie Dean, Susannah Dean,a disabled woman with dissociative identity disorder, and the talking animal Oy. They are his ka-tet, a group joined by fate from various “wheres” and “whens” on an Earth similar to our own. Opposing Roland is Walter O’Dim, the aforementioned Man in Black, and his master the Crimson King.

“There are other worlds than these.”

In The Gunslinger, Roland forsakes his promise to protect Jake in order to continuing pursuing Walter and the Tower. Just before Jake falls to his death he says, “Go then, there are other worlds than these.” The intriguing concept forms the backbone of the series, and not just because it reconsiders what it means to be a ‘hero’ in fiction. In The Dark Tower, the seventh and chronological final book in the series, King describes his multiverse:

“Other worlds. Perhaps an infinite number of worlds, all of them spinning on the axle that was the Tower. All of them were similar, but there were differences…Because in some vital way, they aren’t the real world. Or if they’re real, they’re not the key world.“

In addition to the 4,250 pages that make up the main series, THE DARK TOWER or its concepts began turning up in dozens of King’s books. Characters from ‘Salem’s Lot are in Wolves of the Calla, the fifth book of the series. Insomnia, Hearts in Atlantis, and The Black House are overtly filled with references to ka, the Crimson King, and even Roland himself. In Wizard and Glass, the ka-tet visit a world ravaged by a superflu, a mirror of the depopulated world of King’s behemoth novel, The Stand. Indeed, The Stand‘s villain Randall Flagg (also in The Eyes of the Dragon) is a version of the Man in Black, known variously as Walter Padick, Raymond Fiegler (Hearts in Atlantis) and numerous other names. Pretty much any character that’s had the initials R.F. is likely to be a version of Flagg.

The ‘we’ in Tower

As such, THE DARK TOWER is an inherently intertextual entity. King was inspired by the poem “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” by Robert Browning, which itself takes a title from a line in Shakespeare’s King Lear. Indeed, Shakespeare is said to have taken the name from the fairy tale Childe Rowland, which also speaks of “doors to other whens and wheres,” along with other allusions to Maerlyn and his mysticism.

The number ’19’ turns up so frequently in King’s fiction, from Blockade Billy to 11/22/63. It’s said to be a power number. Yet why does it have power? Is it simply because it is said to be so? Or is it because King started writing the stories at the age 19? Part of what gives it power is the narrator’s voice, the other half of it is the reader’s reception. Which is kind of where the beams of the Tower meet, a focal point point at the nexus of the writer, the work, and the reader.

In our reality, the one that you are reading this article in, King was hit by a truck on 19 June 1999 while out walking in his beloved Maine. The accident that almost ended the writer’s life, and stopped him from writing for a time, not only inspired his 2002 novel Lisey’s Story, but provided a fundamental catalyst for the final three novels of THE DARK TOWER. When he returned to writing, King cast himself as an omniscient character in the novels. King’s in-universe death on that fateful date is something that the ka-tet are determined to stop, believing that King’s continued existence is necessary for their quest to be a success.

King certainly isn’t the first writer to work himself into his own fiction. Grant Morrison famously had a dialogue with his hero in the pages of Animal Man, and is confronted with his responsibility for the death of Animal Man’s family. King also accepts his responsibility and its corresponding burden: choosing to finish the story comes with the possibility that characters will die. Yet if King is responsible, then so are we as Constant Readers. We could have abandoned Roland in disgust when he sacrificed Jake for the Tower, but we chose to keep going.

The author claims to hate the term ‘metafiction’ in the back-matter of The Dark Tower, and it isn’t the most appropriate term here either. THE DARK TOWER deals with Umberto Eco levels of semiotics that consider the complex relationship between the creator, the reader, and the characters. Each becomes responsible for the fate of the narrative, and we all share in the grief of loss and the joy of discovery. It could be argued that the very act of reading is a creative force as well, as we give life to a story by reading it. As the ka-tet continues to encounter allusions to other stories, from The Wizard of Oz to The Seven Samurai and even their own, the power of storytelling (or ‘wordslinging’) is at the heart of King’s saga.

In the coda of The Dark Tower, King actually calls out the reader on this responsibility. Giving us the option to quit while we still have a “happy ending,” King urges the reader to stop if they do not want that spoiled. Of course, after 8 (or 20-something) novels, it’s hard to resist. Just like The Monster at the End of the Book, the children’s book by Jon Stone and illustrator Michael Smollin, we ignore the narrative pleas for the reader to stop. We are just as drawn to the Tower as Roland is. By going on, we also seal Roland’s fate. We are as powerless to stop it as King claims he is. Yet this fated path is exactly where the readers and the film audiences will intersect.

Last time around: The Dark Tower on film

If you have made it this far, dear Reader, then you are as intrigued by the connections to the film as we are. You care not for spoilers, or are already an integral part of the fiction. If the writer, his entire body of work, and the reader are in a constant dialogue with THE DARK TOWER, it stands to reason that film audiences are part of that cycle.

In the aforementioned coda, Roland climbs the stairs of the Tower, witnessing scenes from his life until that point. At the final door, he becomes aware that this is not the first time he has reached his goal. He is transported back to the beginning, with the final line mirroring the first: “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.” The key difference is that Roland is now in possession of the mystical Horn of Eld, and the implication that he must quest for the Tower one last time, but this time it will be different.

Speculation began in May 2016 that the film of THE DARK TOWER would be that final journey when King tweeted the photo above, a picture of the Horn overlaid with “One last time.” The caption gave this great weight: “The Dark Tower is close, now. The Crimson King awaits. Soon Roland will raise the Horn of Eld. And blow.” It was later confirmed by director Nikolaj Arcel that this is exactly the approach the film would take, making the film a ‘sequel,’ allowing for both a loose adaptation and a complete closure.

All things serve the Beam

THE DARK TOWER film is set to continue the intertextual connections of the series, as evidenced by the well-placed shots of a decaying carnival with the word ‘Pennywise’ (from It) displayed prominently. There’s also an unavoidable shot of a photo that looks exactly like The Overlook Hotel from The Shining. A tracklisting for the Junkie XL film soundtrack offers many clues as to the film’s narrative, but is also filled with tantalising clues like ‘His Shine Is Pure.’

These are all things that will be confirmed when the film opens in August 2017. If not, the Constant Reader will always have King’s magnificent body of work to place it in context. Revisiting the clues in other books, and reaching its inevitable end, is a satisfying quest as big as Roland’s. It’s also one that calls you on to go back and revisit it all again. Which is appropriate if you think about it. After all, ka is a wheel.