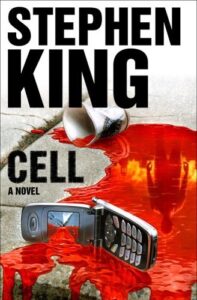

Welcome back to Inconstant Reader, the feature column that explores Stephen King’s books in the order they were published — sort of! Warning: we’ve phoned in a few spoilers.

We always knew that mobile phones would kill us. At the time CELL was published in 2006, Stephen King did not own a mobile (or a ‘cell phone’ for our US cousins). Looking back, nor did I – and I even went so far as to write a ‘prizewinning’ short film that made several ‘amusing’ cracks about them. Oh, how times have changed.

With this horror thriller, King takes technophobia one step further by placing cell phones at the centre of a potential world-ending event. The protagonist this time is another writer, Clayton Riddell, having just sold his breakthrough graphic novel and its sequel. Then the Pulse happens.

It begins with seemingly random acts of violence, but it soon becomes obvious that something is happening to people everywhere. Riddell deduces that it is a signal emanating from people’s phones that are turning them into a kind of ‘zombie,’ and there is a ‘pulse’ that’s driving them in a kind of hive mind. Hoping against logic that his wife and young son are still alive, he eventually meets up with the middle-aged Thomas McCourt and 15-year-old Alice Maxwell. The triptych escapes their native Boston and heads out into a ravaged New England.

CELL picks up pace almost immediately, distinguishing itself from King’s occasionally measured and expository openings. The introduction of other elements and characters are rapidly interspersed throughout the short chapters, as though the narrative points themselves were survivors left by the side of the road. Chief of these is the ‘Raggedy Man,’ a zombie-like creature in a Harvard sweater who appears in their collective dreams. Acting as the primary antagonist, he drives the survivors to a location that will be familiar to readers of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon and Bag of Bones (and later Under the Dome).

King name-checks George A. Romero and Richard Matheson on the dedication page, but others might also find similarities to The Stand: the apocalyptic events, the mass deaths, and two parties being inexplicably led to an inevitable conflict. Yet King’s little ‘ka-tet’ doesn’t have the same sense of moral certainty. There’s no Mother Abigail putting them on god’s path, and these folks are willing to get their hands dirty in the name of survival. Indeed, one of the inciting incidents involves our heroes slaughtering a group of the turned flock. The flock psychically marks them untouchable, so that they are even shunned by other survivors.

This moral ambiguity is arguably the result of the political environment in which the book was born. Five years after 9/11, the world was still on high alert for terrorism. When the Pulse first hits, many characters are heard commenting that it could be extremists at work again. While King was on record a few years later as calling the war in Iraq a “waste of national resources,” he also vaguely references “Muslim teenager[s] who…strapped on a suicide belt stuffed with explosives.” Whether CELL serves a second purpose of commenting on the wave of conservative sentiments following the attacks is debatable. Regardless of intent, it’s clear the world as it stood in the early 2000s was at the forefront of King’s mind while writing this.

It all builds to a fast-paced conclusion, and the page count falls away as rapidly as zombies to a shotgun. The literally explosive climax is bookended by one of King’s more poignant death scenes, and a bittersweet reunion for Riddell. King doesn’t provide all of the answers, nor does he labour the denouement. The ambiguous finale may leave some readers frustrated, but I found it somewhat refreshing.

King’s stance on phones still seems to be in the ‘sceptical’ camp. Indeed, in the 2020 short story ‘Mr. Harrigan’s Phone’ (published in If It Bleeds), he refers to a more recent iPhone as a “high tech Del Monte can” and concludes that “I think our phones are how we are wedded to the world. If so, it’s probably a bad marriage.” So, in some ways CELL is even more relevant now than it was in 2006, with the ties between humans and our devices/accounts making us even more vulnerable than ever. They still haven’t brought about the end of the world though. At least not yet.

When Inconstant Reader returns, we’ll set this site alight with Richard Bachman’s Blaze, a book that King found in the attic somewhere.