Welcome to the feature column that explores a decent number of Stephen King’s books in the order they were published! (More or less!)

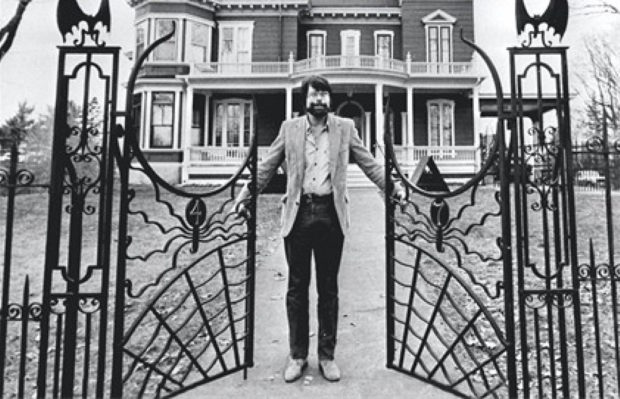

Stephen King knows horror. With at least 80 books under his belt, the unquestionable master of the macabre has shown his authority on the subject dozens of times over. The King of 1981, when this book was first published in small quantities, had released nine books over the course of seven years. (No small feat when those books happen to include Carrie, ’Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and the monolithic The Stand). In other words, he was already one of the more successful writers on the planet.

So, while King’s history and analysis of horror stories comes from a place of authority, it also comes from a place of defence and defiance. The early 80s was a bit of a high point for the proliferation of horror, and it was also being blamed for everything from violent behaviour in teens to the decline of western civilisation. It was kind of like comic books in the 1950s, except they would have to wait another 20-30 years to be taken seriously as a medium. As such, King’s exploration of horror, primarily his favourite books or films up until this point, is ultimately an answer to ‘why do you write about this stuff?’ The answer seems to simply be that when it’s good, it’s really good.

Books and films like The Haunting of Hill House, The Body Snatchers, The House Next Door, and Peter Straub’s Ghost Story – in their various textual, film, and TV adaptations – get the lion’s share of King’s attention. They are evidently his favourites, and King’s informal style often returns to these touchstones as the freewheeling train-of-thought narrative swings in and out of context. Sometimes King will take a sidebar and never return, and at other times he will stick to one thing for what feels like dozens of pages. It’s a bit like that guy at the pub who bails you up to tell you why beer is the greatest. I mean, we’re already in this fine establishment: there’s a good chance we’ve sampled their fine product before, and that we’ll have a drop or two more while we’re here.

Stating that he wishes to avoid “academic bullshit,” King repeatedly comments on the lack of awareness most critics have of the genre. “Most critics cannot be trusted here,” he remarks at one point. It’s a noble approach, one that I certainly stand by in the various projects I’ve undertaken. One can definitely take an academic approach without couching one’s language in a tongue that is antithetical to the traditional audience of the medium or genre. Yet what is this book if not an analytical history of horror, one in which King finds common threads, applies the notion of “Dionysian horror,” and pulls out pseudo-Freudian insight?

Horror has morphed over the last four decades, and become just another one of the many genres that gets overlooked by serious awards bodies. Yet it is experiencing another renaissance in 2019, partly in thanks to a generation of creators who grew up on King’s enthusiasm for the genre. Indeed, King’s work is the subject of dozens of films and TV shows over the next few years alone. Meanwhile, new voices have given us The Witch, A Quiet Place, and the phenomenal success of Jordan Peele’s Us. Which might be where there’s a barrier to entry with this particular tome: a series of half-remembered recaps of books and films that have since become influential icons, written from the perspective of an evangelist who might just be preaching to the converted. On the flip side, there are several films King discusses that are now considered landmarks of horror (Alien and The Exorcist, for example) that he takes a few minor swings at for no discernible reason.

This might be the unspoken message behind much of this book. With enough time, even drive-in dreadfuls will find their worshipful audience. By the same token, it would be unfair to simply label this book ‘dated.’ It is, like much of King’s work, very much working in the moment of the ‘now’ (whenever that ‘now’ happens to be). It’s unquestionably animportant work: a semi-autobiographical list of influences of one of the greatest popular writers of our time, written at what is arguably one of his most prolific periods. (As he notes in the next, he is working on a novel about the fear of nearly losing his son, a book that would become Pet Sematary). The appendices alone should provide the curious with dozens of things to go back and watch if they can find them in this age of homogenised digital content delivery. (A caveat: they are also very middle-class, male-centric, and Anglo in their leanings – ignoring a range of voices that exist outside the US and UK – another indicator of the era in which this was first written).

Unlike King’s engagingly elegant fiction, DANSE MACABRE is at times a slog to read as a singular entity. Some of this comes from its mishmash origin: as he confesses in the afterword, a large chunk of content was gathered from previous pieces he’d written as intros, articles, and college notes. It’s an ambitious project, no doubt, but 1981 King may not have been the best person to tackle it. The accompanying index lets you dip in and out, so if you’re curious to know what King thought of the superb 1979 film The China Syndrome (he likes it) or Kubrick’s The Shining (not so much), you can skip straight there.

Since DANSE MACABRE was first published, there have been countless books, blogs, podcasts, documentaries, and magazines from fans writing and talking seriously about horror. In King’s introduction to the 2010 edition of the book, it’s evident that his non-fiction has evolved to reflect this. While still writing from a pop perspective, King not only concedes that “some” critics get it right, but that there is a wealth of international voices and remakes worthy of further exploration. It would be really interesting to see this entire book written by King now, in light of true crime popularity, streaming content, and the new golden age of television. For now, this tome exists as a (secret) window into a superfan’s mind at a point in time.