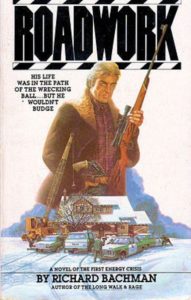

Welcome to the feature column that explores a decent number of Stephen King’s books in the order they were published! (More or less!) Fair warning: there will be spoilers ahead.

There’s a certain vibe to a Richard Bachman book. You can sense the Stephen King motifs lingering in the background, but a Bachman novel feels instantly darker somehow. Stickier. Perhaps, as King explains in the second introduction to The Bachman Books, it’s because they were written with a “low rage, sexual frustration, crazy good humor, and simmering despair.”

So when we enter the world of ROADWORK, we immediately get a sense of something lurking beneath the surface. We first meet the unnamed Barton George Dawes during a vox pop interview about a pending highway construction, and boy does he have some opinions about that. Dawes himself seems unaware of his actions, so when we catch up with him a few years later buying guns, we form our own conclusions about his intentions well before he does.

The four Bachman books published between 1977 and 1982 can be taken as alternating pairs. If The Long Walk (1979) finds comparisons is the dystopian game show of The Running Man (1982), then the psychological menace of ROADWORK can be most closely paralleled by Rage (1977). While that earlier book remains problematic, and now completely out of print, the psychological undercurrent of this book remains grounded and eerily normal.

We get a sense almost immediately that there is something up with

Barton George Dawes. His inner dialogue with ‘Fred’ both antagonises him and pushes him towards the brink. His reaction to losing his house and workplace to the construction plans is not typical. Instead of looking for a new home or relocating his business, both of which were viable options, he has sat on the decisions and done nothing.

If ROADWORK is a meditation on the grieving process, then Dawes is a man stuck at the denial stage. It may not be a new grief either: he’s been with his wife since their unplanned pregnancy, and his indifference upends her life as well. Where he remains in arrested development, his wife acts. In fact, everybody around him does. Colleagues move on to other jobs and Dawes merely mocks them while sitting in an empty neighbourhood eating TV dinners.

King’s own grief plays some part in the creative process, having recently lost his mother to a “lingering cancer” that had “taken her off inch by painful inch.”

“I think it was an effort to make some sense of my mother’s painful death the year before …I was left both grieving and shaken by the apparent senselessness of it all…ROADWORK tries so hard to be good and find some answers to the conundrum of human pain.”

It is slowly revealed that Dawes is grieving for more than his house and wellbeing. ‘Fred’ turns out to be his young son Charlie Fred Dawes, who died several years before from brain cancer. Dawes’s rage against the machine is partly against the government, but wholly against the futility of existence.

What’s remarkable is how much goes on without much going on. Unlike the creeping darkness found in a straight-up King horror, Bachman books tend to focus on the horror of the everyday. Dawes becomes a firebombing vandal. He sleeps with a random woman he meets hitchhiking. He consorts with mobsters. He has a literal loaded gun in the garage. Dawes has “read all of Kurt Vonnegut’s books. He liked them because they were funny.” There’s more than a little Vonnegut in there. So it goes.

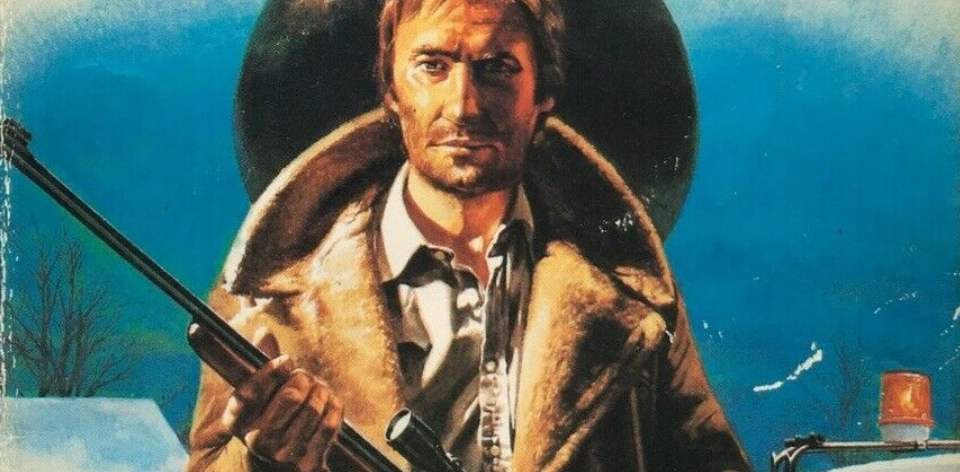

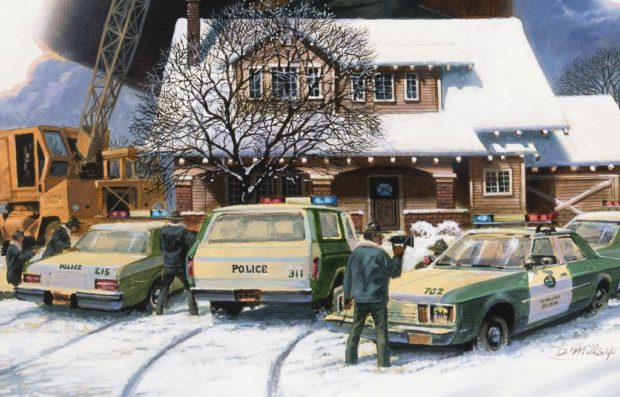

The explosive finale, hinted at by the sensationalist paperback cover, is an inevitable climax after a slow build-up. King/Bachman’s pacing allows us to see the forest for the trees in a way that Dawes never allows himself in his fallow pit. In a coda, a documentary validates some of his actions, but do they create any change? Or as Dawes puts it, “The fucking you got was never worth the screwing you took.“