Welcome back to The Read Goes Ever On: a casual and personal reading (and in some cases a very slow re-reading) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Never before has the title of this column seemed more appropriate. The intention was to start with the Tolkien books I hadn’t read and fill in the gaps of the grand legendarium. Eleven books later and we land here, on a collection of poetry branching off from a side character. This is a road that has continued to go on long past the ‘quick’ overview of Tolkien outside of The Lord of the Rings.

It goes without saying for the initiated, but one of the particular joys of Tolkien’s work is his engagement with languages. His recognition that language is not just a sum of its various influences but also a living entity has kept his world alive in more ways than one for several generations. Indeed, Philip Seargeant argues that Elvish has had a more profound impact as a universal language than Esperanto.

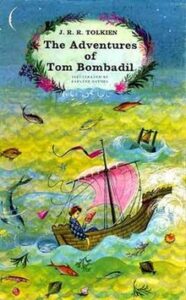

Of course, language exists in more than one form and stories are some of the most powerful conductors of language and ideas. If Tolkien’s main stories are a means of giving us a window into his fictional worlds, then the songs and poetry we encounter are glimpses of the whole universe on the other side of the frame. They are the artefacts of a ‘forgotten’ age, the stories told within the stories of how things came to be. Which leads us to THE ADVENTURES OF TOM BOMBADIL, ostensibly presented as an actual translation from the fictional Red Book of Westmarch penned by the Bagginses and Samwise Gamgee.

Who is Tom Bombadil?

The enigmatic character most readers first meet in The Fellowship of the Ring is possibly the oldest in existence in Middle-earth. The figure the Elves call Iarwain Ben-adar has watched the steady march of the First Age through to the Fourth, and it is commonly believed that he is one of the Ainur, the Holy Ones who created the world. Indeed, the One Ring seemed to have little to no effect on him – with Gandalf guessing Tom would just lose track of the powerful item if entrusted with it. Others have speculated that he could be anything from the living embodiment of Arda (the Earth) or Eä (the universe) or even a manifestation of the forests themselves. Essays have been written interpreting his nature. Known for lengthy chats in his Old Forest home, Gandalf had a palaver with the fellow before the wizard departed Middle-earth. Tom was said to be “not much interested in anything that we have done and seen.”

First published in 1962 as a light follow-up to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien described the collection (in a December 1961 letter to illustrator Pauline Baynes) as coming “not a unity from any point of view, but made at different times under varying inspiration.” Of the 16 poems presented, some of these (‘The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late,’ ‘The Stone Troll’ and ‘Oliphaunt’) are extracts from chapters of LOTR. Others come from earlier texts, related texts or the ‘fairy stories’ that made up Tolkien’s extensive writing. Only one of the pieces (‘Bombadil Goes Boating’) was written specifically for the volume.

The first two of the poems – ‘The Adventures of Tom Bombadil’ and the aforementioned ‘Boating’ – are also the only ones related to the titular character. These directly link the book and its contents to the Middle-earth legendarium, and indeed the publishing history of LOTR. Tolkien purportedly crafted the story when his then young son Michael was given a Dutch doll, one that his brother Michael promptly flushed down the toilet. Tolkien subsequently wrote the poem and published it in Oxford Magazine in 1934, at one point pitching the material as a sequel to The Hobbit. So, in more ways that one, we can see the origins of Middle-earth in this poem.

The remainder of the contents are widely described as an assortment of bestiary verse and fairy tale rhyme. ‘Perry-the-Winkle’ (in which a lonely troll visits the Shire), ‘The Mewlips,’ ‘Oliphaunt’ and ‘Fastitocalon’ all fall squarely into this category, presented as if written by Sam Gamgee. On the flip side, Bilbo’s ‘The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late’ and ‘The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon’ drew their real-world inspiration from Tolkien’s light-hearted imitation of medieval works. While no great shakes as literary exemplars, Tolkien imagined it would be the poem that ultimately led to the nursery rhyme ‘Hey Diddle Diddle (The Cat and the Fiddle).’

“I walked by the sea, and there came to me,

as a star-beam on the wet sand,

a white shell like a sea-bell;

trembling it lay in my wet hand.”

— The Sea-Bell (or Frodos Dreme)

Of particular note is ‘The Sea-Bell’ (subtitled ‘Frodos Dreme’). While Tolkien once wrote that it was the “the poorest” of the lot, W. H. Auden disagreed, saying it was “wonderful” and “in my opinion his finest.” It stands out from the other ‘Hobbit written’ poems for its more dramatic and melancholy nature. On a technical level, it is some of the most complex poetry Tolkien wrote. What began in the 1930s as a poem called ‘Looney’ is the tale of a narrator ferried off to a mysterious land on the titular white sea shell. When he eventually makes his way home he finds himself changed and isolated from the people he knew. In the context of the Campbellian hero’s journey, here we see the hero returning to where he started but forever altered.

It would be easy to draw an analogy to a soldier returning from the First World War, with similar themes that pervade several of Tolkien’s works. Within the Middle-earth universe, there’s unquestionable parallels with the end of The Return of the King and by extension Bilbo’s Last Song. Despite the subtitle, Frodo is not the narrator of the piece — but together with this poem, there is a similar cyclical aspect to their shared journeys. Taken together with ‘The Last Ship,’ the companion poem and final entry in the book, there is a line-through about barriers and sailing through the threshold between one world and the next.

While THE ADVENTURES OF TOM BOMBADIL may seem lightweight in comparison to the published epics that preceded it, the collective texts are one of the more vital pieces of the larger puzzle. Presented as though written by the very people of Middle-earth, and passed down the generations to us, it’s the closest we get to being in that world. It was something Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and Peter Jackson understood when they penned a certain film’s prologue, making their own interpretation and amalgamation of the text: “History became legend. Legend became myth.”

Is this Namárië!? Where do we go from here? For the first time since starting this, I genuinely don’t know. This ends the first phase of my long journey through the legendarium in the lead-up to the Amazon series this year. Yet there’s so much more. I skipped the standalone Beren and Lúthien. The entirety of Christopher Tolkien’s 12-volume The History of Middle-earth. The History of the Hobbit. There’s also the more recently published The Nature of Middle-earth edited by Carl F. Hostetter. Not to mention Tolkien’s voluminous work outside of Middle-earth. Whichever road we take, it goes ever on. Or back again.