Welcome back to Inconstant Reader, the feature column that explores Stephen King’s books in the order they were published — sort of! Here’s one where Mr. Gray is the villain and I don’t know how to feel about that.

“Well, I don’t like DREAMCATCHER very much,” Stephen King told Rolling Stone in 2014. “DREAMCATCHER was written after the accident.” He is, of course, talking about the near-fatal incident in which the author was struck by a van. The aftermath left him in severe pain, only able to write in small snatches, and under the influence of painkillers.

Which is probably why it’s a book that is very much about the body. It contains elements in which various characters are unable to fully control their motor functions. Written longhand with a Waterman fountain pen, which King describes in the afterword as “the world’s finest word processor,” King has spoken openly about readers being able to see the influence of the drugs there. He’s not wrong: it’s one of the more disjointed outings from King I’ve read. More than that, you can feel his pain through the body horror and uncomfortable language.

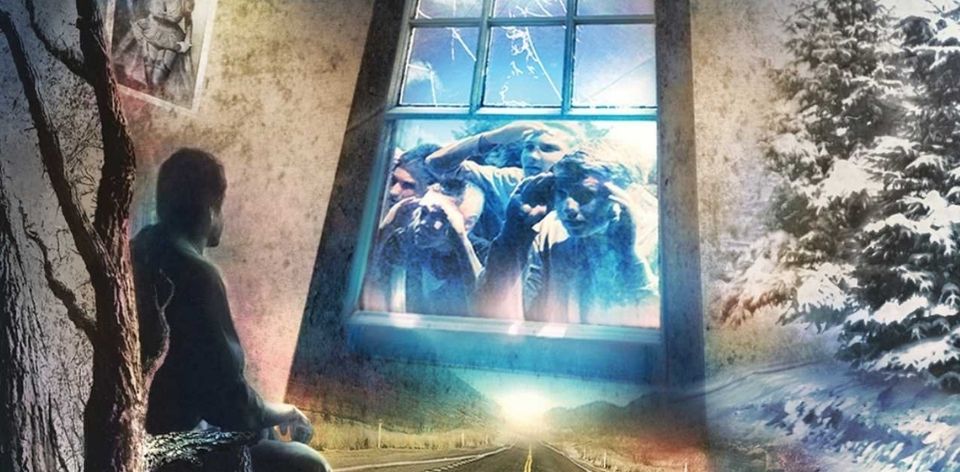

You already know the narrative to DREAMCATCHER well. It’s about a group of boys from Derry who reunite as adults to fight a powerful force together. Or are you thinking of the other one. (If you are, you’ll happily find references to It scattered like breadcrumbs throughout). Here, four childhood friends – Jonsey, Beaver, Pete, and Henry – plan to meet to go hunting in the Maine woods. They find themselves caught in the quarantine zone of an alien crash site instead.

“It’s Derry, it’s 1978, and it will always be 1978.“

What follows is an odd mix. There is a sense of mystery around the presence of red alien fungi, and a man who is apparently being torn apart from the inside by alien ferrets. Eventually, it’s discovered that some of them are being possessed by alien minds, including the military clean-up operation being led by a man named Kurtz. (The horror! The horror!) Plus, the Derry boys soon find that they are all still connected by a kind of ‘dreamcatcher’ formed by their intellectually disabled friend ‘Duddits’ — who may just hold the secret to defeating the aliens.

If you are at all familiar with King, then you might think that this all sounds a bit like a cross between It and The Tommyknockers, with a little bit of The Mist thrown in for good measure. Indeed, it’s curious King should even seek to recall his last alien invasion book, as he is on record as calling The Tommyknockers “an awful book.” While King may have been overstating his ire against that book, it did sacrifice some character development in the course of its body snatchers plotting. DREAMCATCHER almost suffers the opposite malady, with some intriguing characters lost in almost incoherent plot swings. We spend long stretches with the military before randomly cutting back forth to childhood vignettes. As King ramps up to the climax, the intercutting gets more intense, arguably to the detriment of the narrative.

That’s before we even get into some of the more problematic aspects of the book. An elongated set-up grinds its way through what feels like a hundred pages of lengthy fart descriptions. (There are, according to a Kindle search, almost 50 different mentions of farts or farting). Some of this makes sense, as the primary point of body horror, known as the shit weasel, works its way out through the rectum after all. Yet there’s only so much time one can spend on body horror before it becomes overwhelming. In fact, thinking back on it, some of the reason why I was so uncomfortable with the material was due to my own ‘body horror’ journey over the last year or so. I know all too well the literal pains of one’s body turning against itself and not having control over what it will do next. As weird as it sounds, perhaps I treated DREAMCATCHER with arm’s length detachment because it got a little too real. That and the fact that the main alien presence is called Mr. Gray.

“To ignore the body…seemed both wilful and stupid…”

Less forgivable is the treatment of intellectual disability, extending a theme that has previously earned King a reputation for a kind of ableism, one that is only rivalled by his constant return to ‘magical Black characters’. The character of ‘Duddits’ is introduced by means of a hate crime/assault by bigger kids, ones that use the ‘r-slur’ to describe him and his school colleagues. King himself uses the r-slur about three dozen times in the book, mostly by characters who are being deliberately antagonistic but occasionally from the omnipresent narrator voice too.

Then there’s Duddits himself. He speaks almost exclusively in a vowel-based language (‘Ooby-ooby-oo – we gah sum urk oo-do-now’), which is King’s attempt to emulate the speech patterns of someone with a disability. He’s imbued with otherworldly abilities in the same way gentle giants Tom Cullen (The Stand) and John Coffey (The Green Mile) had before him. This is, of course, exacerbated by the performance of non-disabled actor Donnie Wahlberg in Lawrence Kasdan’s film adaptation, one that is possibly the only thing more slammed than the book.

For Constant Readers, there’s stacks of appreciated references. Being a Derry book, there’s a plaque dedicated to the Losers Club and graffiti saying “PENNYWISE LIVES” in a clear nod to It. Then there’s this even more overt passage:

“The years of 1984 and ’85 were bad ones in Derry. In the summer of 1984, three local teenagers had thrown a gay man into the Canal, killing him. In the ten months which followed, half a dozen children had been murdered, apparently by a psychotic who sometime masqueraded as a clown.”

For Dark Tower devotees, Duddits lives at 19 Maple Lane, and the number 19 comes up multiple times. Duddits later lives with his mother on Dearborn Street, a reference to name of Dark Tower protagonist Roland Dearborn. Of course, the titular Dreamcatcher is an appropriation of the Miꞌkmaq tradition, referred to by King with the previously accepted spelling Micmac. The First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, including the northeastern region of Maine, Micmacs featured prominently in Pet Sematary and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon.

Through this, King almost manages to stick the landing. There’s flashes of brilliance, not least of which is a sequence set inside a warehouse of memories. Once we hit the magical three-quarter mark, King steamrolls into the finale too. Which makes DREAMCATCHER a frustratingly curious outing, one that almost foreshadows Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach novels. Perhaps King was just once again ahead of his time.

When Inconstant Reader returns, I’ll take a look at King’s anthology collection, Everything’s Eventual, a collection of 11 short stories and three novellas originally published between 1995 and 2001.