For the last few years, we have been living in the future.

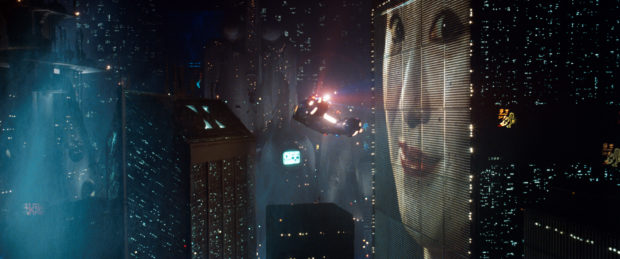

At the very least, we’ve now gone past the events of BLADE RUNNER in the real world. The 1982 cult film opens in Los Angeles of 2019, a gritty vision of future noir. Yet for a film where corporate power literally dominates the landscape, and raises questions about what we can see and remember, it’s increasingly becoming more science than fiction.

We now live in an time with exponentially powerful AI, where truth is labelled fake and the fraudulent is shared at memetic speed thanks to social technology. So, it’s no surprise that forty years after posting disappointing box office results, director Ridley Scott’s vision persists through spin-offs, sequels and restorations.

Electric sheep awaken

BLADE RUNNER as we know it today is a very different beast to where it started. The film we enjoy today, thanks to Scott taking multiple bites at the cherry, is literally a different cut to the one audiences saw in theatres when it opened on 25 June 1982.

Yet the original version of the tale was in Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), a novel that touches many of the same story beats that we see in the film. Set in a post-apocalyptic San Francisco, a bounty hunter named Deckard tracks down six escaped Nexus-6 model androids. In the book, a global nuclear war has left most animal species extinct, resulting in many people owning synthetic animals (hence the title). Owning a live animal is a luxury status symbol. (We still see hints of this in the film when Deckard talks to assassin Zhora about her synthetic snake).

Screenwriters Hampton Fancher and David Peoples borrow much of Dick’s core story. Replicants are manufactured by the Tyrell Corporation to work on space colonies. When a group of six replicants led by Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer, escape and make their way to earth, world-weary cop Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) reluctantly agrees to track them down and ‘retire’ them.

When we celebrate the 40th anniversary of BLADE RUNNER, we’re marking the theatrical release. While opening strongly in the late June weekend, its proximity to a packed summer of sci-fi and fantasy hits — which included The Thing, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Tron and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial — ultimately impacted its box-office. Yet initial criticisms, which ranged from “Blade Crawler” (LA Times) to “sci-fi pornography” (Columbia Record), may have partially been the result of last-minute studio interference. What audiences saw in 1982 was a print that contained an ill-conceived voice-over, several cut scenes and worst of all, a happy ending shot in the sunlit wilderness.

While intended to leave audiences on an upbeat note, it’s a tonally jarring change of location that had the complete opposite effect. In fact, some of the footage was lifted from outtakes of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), meaning it’s literally from another film entirely. “I did it because I thought it might actually affect the outcome of the movie,” said Scott in Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner. He was right, of course, just not in the way the studio intended.

If you’ve watched the movie since 1992, you are now watching the superior Director’s Cut, which removes the voice-over, happy ending and restores several key scenes. It not only makes for a more cohesive picture, but also strengthens the implication that Deckard himself is a replicant. (This was partly undone by Blade Runner 2049, but that’s a whole other conversation). The Director’s Cut was replaced by the 25th anniversary Final Cut in 2007, the only version over which Scott retained full artistic control.

Things you people wouldn’t believe

Regardless of your preferred version, BLADE RUNNER remains salient due to its distinctive audiovisual style and it’s fundamental interrogation of the question ‘what does it mean to be human?’

This is explored in the dynamic between Deckard and Rachel (Sean Young), a replicant created by corporate overlord Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel) as something of an experiment. Rachel doesn’t know she’s a replicant, with all of her memories and photographs as manufactured as she is. It’s one of the signals to audiences to not quite trust anything we see or are told. In the Director’s Cut onwards, their relationship gives us pause to consider Deckard’s dreams, ones that have been interpreted to also be implants.

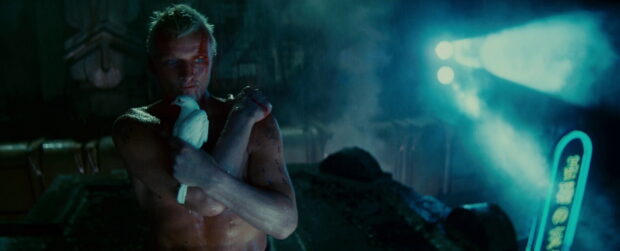

At the opposite end of the scale is Roy Batty, a replicant who knows exactly what he is and simply wants to live. In the conceit of the film, replicants have a failsafe of a four-year lifespan. Rutger Hauer, who had only made his Hollywood debut a year earlier in Nighthawks, was primarily known for his work with Paul Verhoeven (Turkish Delight, Soldier of Orange, Spetters) at the time. With Batty, he bursts onto the US scene as a character who is simultaneously charming as hell while being gleefully violent in the process. He is the definition of an anti-villain. Yet it’s in his dying moments that he shows Deckard exactly what it means to be human, uttering one of the most famous soliloquies in film history.

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion… I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain… Time to die.”

Perhaps the most iconic thing about BLADE RUNNER remains its imitable vision of the future. From the moment BLADE RUNNER opens, it establishes a time and place. Not just the then-future LA of 2019, but in the very fabric of the film. As the digital green readout of The Ladd Company’s logo prints its way across the screen, we know this is the future as imagined by the 1980s.

While drawing on a tradition that stretches back as far as 1927’s Metropolis (as suggested by Mark Cousins in The Story of Film), its blend of neon lights and smoky shadows draw just as much influence from crime noir of the 1940s and 50s. So much so that Paul M. Sammon named his definitive book on the history of the film Future Noir.

With its sultry sax and synth combinations, the Vangelis score is practically another character. As the opening chords of the Main Titles kick in, we’re instantly transported into this recognisable but also alien future. From Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks to the Heavy Metal stylings of Moebius and his contemporaries, BLADE RUNNER‘s Los Angeles is filled with overlapping influences from Asian megacities and numerous bande dessinée. Perpetually shrouded in rain and smoke, it has been copied and reworked countless times, from Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 to Loki and South Park: Post Covid.

Future is now

“If you are ahead of your time, it’s as bad as being behind the times,” remarked Scott years later. While BLADE RUNNER is now considered to be a classic of the genre — complete with novels, comics, anime and ultimately a 2017 sequel — back in 1982 it was just another fine example of the form in a highly competitive summer.

As the franchise continues to explore a future that never came to be, not least of which is the anime Blade Runner Black Out 2022, one wonders how far we are from testing the limits of our own humanity. For every touchstone we see reflected back at us from the dark mirror of 1982, we’ve developed things they wouldn’t believe, from war, to pandemic and tiny computers we hold in the palms of our hands. Whether BLADE RUNNER anticipated this future or influenced it is yet to be seen.

If only they could see what we’ve seen through their eyes.