Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

Remember that bit in director Marc Forster’s Quantum of Solace when Bond just sat down and had a chat for a few hours? Or 007 disguising himself as a dispatch-rider in A View to a Kill? No? Ian Fleming does. Impressive given that he died decades before either of these short stories were adapted! If it wasn’t for his outdated views on all minority groups, it’s like he’s a seer(cret) agent.

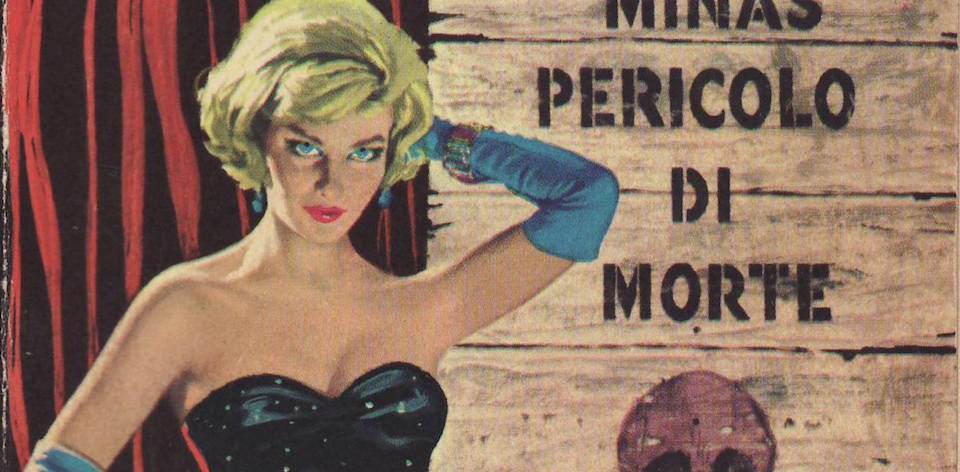

Some of Fleming’s most experimental Bond stories to date, and perhaps in the history of his published works, this collection of short tales (published in 1960) have the most fascinating transition from script to story to screen. Four of the five stories in this set were originally bound for an unfilmed television series. As such, there’s a certain Bond-villain-of-the-week vibe to several of them.

Yet Fleming also uses the short form to play with Bond from different angles and is arguably the first time since From Russia with Love (1957) that have so consciously played with the form. The aforementioned Quantum of Solace is the most radical departure from the previous novels, with Fleming using W Somerset Maugham as an inspiration. First published in Cosmopolitan in 1959, Fleming is almost metafictional in his approach. The Governor of Nassau tells Bond a story of a couple. It’s picks up on an existential thread that has followed Bond through several novels, and is in fact based on a story told to Fleming by his neighbour (and lover) Blanche Blackwell.

The Hildebrand Rarity is a similarly incongruous Bond story, with the spy mixed up with the sexy selling of seashells in the Seychelles. The abusive Krest is one of the best Bond villains in recent memory, one who could fit into any era of Bond. His physical and verbal abuse of everyone around him makes him purely toxic, devoid of any other grandstanding, complicated plans, or convoluted death traps. He does wield a stingray tail though. Surely that’s up there with the most villainous of accoutrements from the Macy’s accessory wall.

The other stories are more straightforward. Indeed, the titular tale andRisico formed the basis for the film For Your Eyes Only (1981) with Roger Moore. Curiously, while lead story From A View to A Kill doesn’t dance into the fire, it did start its life as a backstory for Hugo Drax, the villain from Fleming’s third Bond novel Moonraker. This would have undoubtedly pushed the experimentation further, and I would have loved to see how this panned out as either a TV episode or as the planned prequel.

Fleming’s estate would posthumously publish additional short stories in Octopussy and The Living Daylights (1966). So, this is one of the rare collections that gives us insight into how Fleming saw individual shorts working together. For most authors, a collection like this may have indicated a weariness with a creation. Fleming/Bond have expressed as much on a number of occasions, most notably in semi-nihilistic Moonraker.

Yet there were another 5 novels after this from Fleming, almost 25 films, and dozens of other books from a variety of authors. If this collection demonstrated anything, it’s that Bond was more than just a blunt instrument with life beyond his own world view.